Dr. Amanda Kost is an Associate Professor in the Department of Family Medicine (DFM) at the University of Washington’s School of Medicine, where she teaches, conducts medical education research, and cares for patients. In June 2021, Dr. Kost added to these and her many other professional demands the position of Medical Director for MEDEX Northwest. While many across the DFM know and admire Dr. Kost, there are likely some among us who still have some catching up to do. We sat down with Dr. Kost recently with exactly that in mind.

Q: You received your B.A. from Cornell in 2001 and your M.D. from SUNY-Buffalo School of Medicine in 2005. Check and double-check. But how is it that you decided to earn a M.Ed. in Measurement and Statistics in 2016, well into your career?

I completed my Family Medicine Residency here in 2008, then I practiced in the community for two years (2008-2010) at the Seattle Indian Health Board, and then I came back to start in the Medical Student Education Program. At that time, I was trying to figure what direction to take in terms of the academic part of my career – scholarly pursuits, scholarship, that sort of thing. There was one option that appealed most to me: the Teaching Scholars Program (TSP). The TSP is designed to take health professionals and make them into excellent teachers, people who can develop and administer curricula and do a little bit of educational scholarship on the side.

When I met with my department chair, Dr. Tom Norris at the time, it became clear that I was really interested in outcomes-based research. I was part of the Underserved Pathway when I began [with DFM], and that program had been around long enough at that point that we could start to study the outcomes and see what had happened to the students who had gone through it. I didn’t have any skills in this area, but I was interested in it. Dr. Norris suggested I go to the UW College of Education to see what they had to offer. They offered a degree in Measurement & Statistics, which really interested me. Dr. Norris supported my decision to enroll, acknowledging in part my interest in it, but also recognizing how few members of DFM did educational research.

It took me four years, 2012-2016, to complete the degree, one course at a time! Of course, all the while I was doing clinic, I was involved with Underserved Pathway & the Family Medicine Interest Group, I was advising, I was doing all my medical student education stuff, all of that on top pursuing this degree. It was definitely a lot, but it worked out.

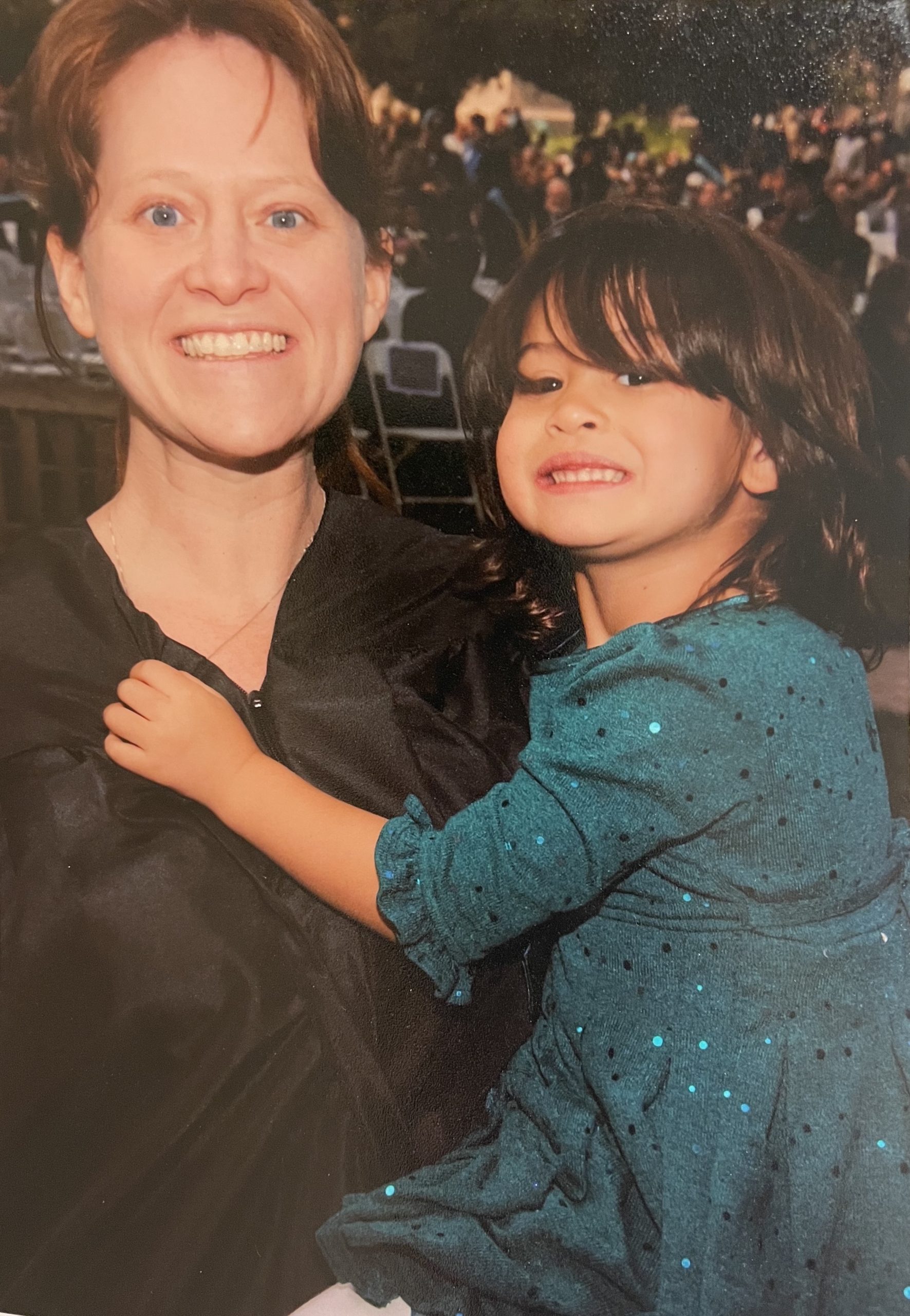

I used to joke that my daughter and my master’s degree were the same age, because I started right after she was born. When she turned four, I graduated. We actually walked across the stage together when I received the degree.

I got involved from there with the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) and the educational researchers there. I was really interested in Family Medicine interest groups, for example, to see if they were influencing career outcomes at all. Are we successful in helping to guide medical students into primary care or family medicine careers? How good are we at getting them into rural and underserved settings? Are we meeting the workforce needs of the most vulnerable populations?

Beyond your own writing and academic publishing, you also maintain an editorial relationship with academic journals, is that correct?

Yes, I am an associate editor for PRiMER (Peer-Reviewed Reports in Medical Education Research), an open-access scholarly journal of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM). I also work on Teaching Physician, which is an STFM website for teaching. I’m currently working to set up an editorial board for Teaching Physician and have associate editors update the content. This is an especially good way for people who are more interested in teaching and curriculum to get into editorial roles, because right now it’s largely researchers in those roles.

Tell us more about that. It sounds like you are saying that there are researchers on the one hand, and—who exactly on the other?

Okay, I go to these family medicine meetings – and it’s probably the same in the PA world too –where the people who do research are largely folks who have been trained to do research. It’s hard for other people who are interested in it but who aren’t trained researchers to break in and make the time and figure it out. And so, my goal has always been to help faculty find opportunities if they’re interested in scholarship, or interested in editorial stuff, that sort thing. Because I think that those silos of researcher vs. teacher vs. clinician are… well, if we give people a way in, I think they’ll want to do this. But a lot of times people can’t even see the path forward, because they are just crushed by their clinical work or teaching load.

So the advantages go beyond assisting the individual person interested in research to supporting the practice or the community at large?

Yes, I think it benefits the state of health professions education as a whole. I think you want someone who is embedded in the experience to be doing the research and doing the scholarship, and to be thinking about how we could do all this better. Of course, formally-trained researchers bring a lot, no doubt. But it’s different if it’s the person within the system or within in the structure leading the area of inquiry, thinking about how you make things better. A lot of people are interested in doing this. They just don’t know how to do it. It was super confusing to me when I started. It’s not something that’s easy to navigate.

Is this commitment part of what you bring to MEDEX Northwest and to the PA profession?

You know, part of doing a master’s degree that was beneficial was that I had to take all these distribution requirements, too. So for instance, I took a course on motivation and what motivates people to learn, and a course on how people learn, and a course that asked Why do we have education? and What do we think about curriculum? and that sort of thing.

As a result, I received a lot of formal education that I think is really useful for faculty development. Of course, not everyone is interested or has the energy to spend four years of their life doing this. But I think one of the key things that I learned in that experience, and have learned leading the Teaching Scholars Program and working with other people, is that people are really interested in learning these things. They’re really interested in becoming better teachers.

I think health professionals are some of the worst people when it comes to this. Because we’ve had hard jobs, we tend to think Oh, how hard could teaching be? It can’t be that hard, I learned all this complicated biochemistry! But once they get started, they realize that there’s a whole skill set, a whole knowledge set, that you need. And so, it’s hard to figure out how to go about getting that, and it’s even harder to know how to apply that.

I think this is what I bring to the table. I can take these pretty formal, theoretical, maybe esoteric things and I can translate or interpret them into something that is going to be useful to a teacher, something that can be applicable that day to improve their teaching and the learning of their students.

I try to hold onto the question What were you, the learner, like before you knew all this stuff? The further on in your career you go, the more you tend to forget what it was like when you didn’t know anything. You tend to forget how hard it all was. So it’s important to encourage other teachers to keep this in mind and to try to have empathy in that sense. And of course to have supporting theory behind it as well.

Have you found PA school to be different from medical school in these ways?

No. I think medical school and PA school are very similar in terms of how we recruit and get faculty ready. We say Hey, you made it through! And you’re interested in teaching! Have fun! And we might give you some things along the way, and maybe you’ll sign up for a specific faculty development program. But there’s no formal path to becoming a health professions educator, right? It’s kind of whoever’s interested in it can sign up for it.

You get these academic jobs and then you have to figure out what to do. People from both disciplines bring passion and skills and are really motivated by wanting to make the world a better place. I don’t see that there’s any difference in that. The content that they’re teaching is different, and the pace is different, and so you need to think a little bit more about that. But the underlying approach is not fundamentally different.

What else have you learned through working with PA faculty?

What’s been really interesting working with them is getting a sense of just how accelerated the curriculum is, and how challenging it is to cover all of that in the given period of time. And just the level of stress that people feel, right?

It took seven years before I was “fully grown.” There were a lot of people who helped me out during that time. And I think PA faculty feel this deep responsibility to make sure that their graduates are ready for practice. They know they’ll get help from those in their practice, but they’re not going out to residencies for the most part, right? They’ll certainly be trained by their practices, by their sites, by their clinics, by the in-patient units that they work on. But there’s this deep sense among faculty of I need to give this person my all. We don’t have time to waste. There’s not three more years coming after this where someone can fix this later. We need to do the best by these people that we can now, so that they’re ready to go.

So faculty can be just about as stressed as the students?

Yes. But it’s also a motivating factor to make sure the students have the best education possible. There’s less wiggle room for the faculty because there’s less time. There’s this sense that the bar is very high, and it’s challenging to reach it, you know? And so you feel that you must work extra hard to get there. But they’re motivated because they’re doing something that is very important to the health of the public and the population.

I was not someone who thought I’d end up in academics. But I really do enjoy teaching. I guess I’m like what a lot of family doctors are like: I can get excited about anything.

Here’s the ARC-PA description of a medical director’s duties in the context of PA education: “A physician assigned to the PA program and who reports to the program director. The FTE [full-time equivalent] assigned to the medical director is specific to this position/role. Supports the program in ensuring that didactic and clinical instruction meet current practice standards as they relate to the role of the PA in providing patient care.” Does this pretty much cover what you’ve been up to over the past year?

I’ve certainly been learning a lot more about how PA programs are accredited, about the content list and what the core areas of study are, and about all that’s required to sustain a PA program. And I’m still coming to recognize and appreciate where the areas of need are that I can uniquely assist with.

Early on, for instance, people have pointed out the need for faculty development, and the need for promoting scholarships, those sorts of things. But I still feel like I’m learning a lot. What’s the academic year like? What’s the curriculum like? Where can it be improved? What is working well that should be emulated? I’m still in the getting-to-know-you stage.

In my experience of working with PAs clinically, I find that they function very independently. I worked with a PA at the Seattle Indian Health Board, for instance, who had been there for like 30 years, and he was great at what he did. He rarely asked questions but knew just when he needed to.

So, I guess I view this role with MEDEX as more of a supporting than a supervisory role. And again, that just comes down to the fact that people invested seven years in getting me here. The pace of my education was slower and so I fundamentally had time for more things. I would hope that mine is a sort of modeling role. PAs, MDs, DOs—we’re working inter-professionally, we’re all in this together.