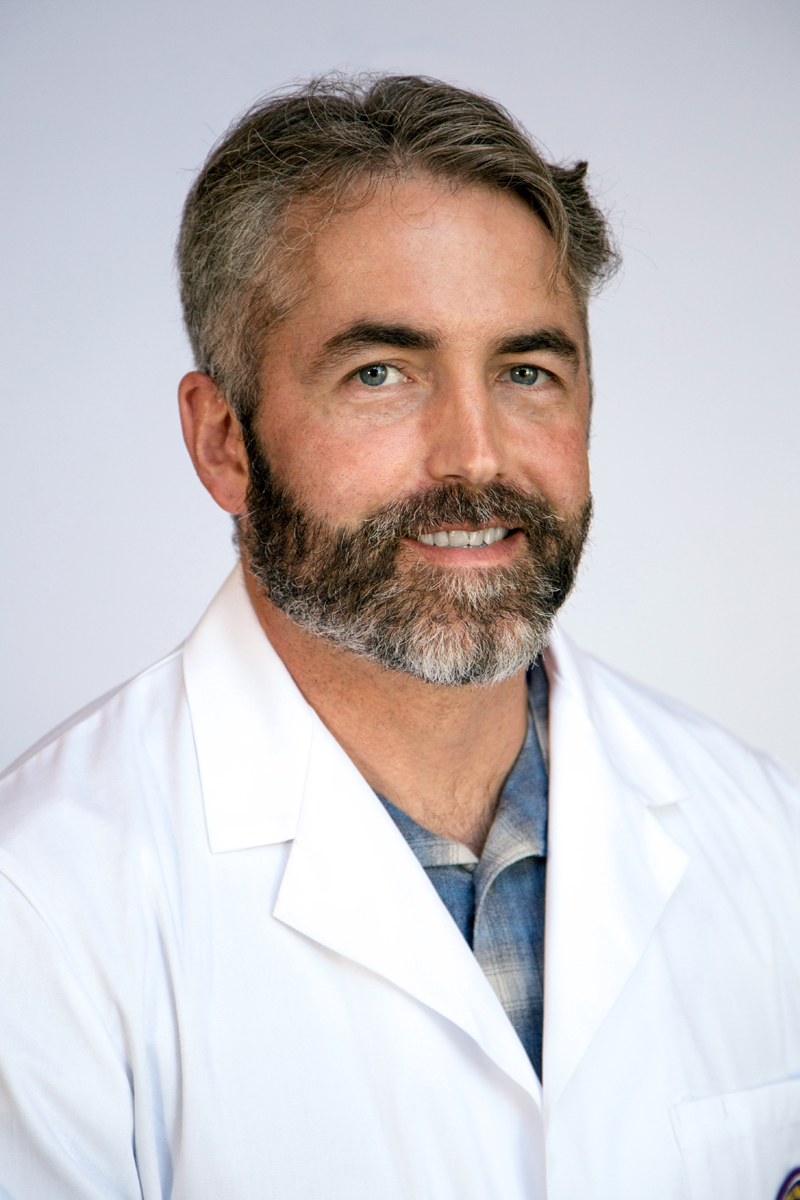

Paul Hastings of MEDEX Seattle Class 51 spent seven and a half years as a combat diver for US Army Special Forces on military operations throughout Asia and Afghanistan. Additional training as a medic, or diver medical technician, enabled him to attend to both his fellow combatants and the local citizenry.

“I think I was selected to do that mainly because of my background in the sciences,” he tells us. “You know, just understanding chemical pathways within the body.” Paul had come to the military with a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and molecular biology from Michigan State University. He was close to completing his studies at MSU when 9/11 occurred, changing the focus of his life from that point on.

He had worked part-time in a lab during his college years, but didn’t want to return to the lab after graduation. So, in 2003, Paul joined the military. “Ever since I was a kid, I had an interest in the military,” Paul says. “If there was a war to be fought, I wanted to be a part of it.”

Initially, Paul chose a career as a nuclear biological and chemical soldier. “I selected a military specialty that I thought might be in line with my degree,” he says. His basic training occurred at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, which was followed by a year in Korea.

Paul originally envisioned serving a short stint in the Army for the experience, then getting out. In time, however, he came to realize that he was doing something he actually enjoyed, and began looking to advance his military career instead.

Paul set his sights on Special Forces, and was soon accepted. He finished up his time in Korea and returned to the States in 2005 for his Special Forces training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

He completed his training successfully, but questions persisted. Did he have what it takes, he wondered, to actually survive on a SF team? After all, he said “you’re not a real Special Forces soldier until you go to combat and actually prove your mettle on the battlefield.”

Special Forces is a highly competitive environment with highly vetted individuals. Upon arriving at his designated company at Fort Lewis, Washington, he was given two options: work at the company level, or join the Dive Team which are historically the most competitive teams in Special Forces. “I chose the Dive Team,” Paul says. “I was lucky to be placed with a team of professionals who were determined to train me to be a combat diver and mentor me through the first years of life in my new profession.”

To be a combat diver, one must learn how to circumvent basic survival mechanisms in the brain to stay calm under water and in stressful environments. “Being out of our natural environment, under water, can bring dramatic and overpowering survival instincts into play, which cause panic. Panic can bring about unfortunate outcomes in an unforgiving environment like the ocean,” Paul says. Working this way requires finding an inner Buddha, as he calls it. “I think that’s what gives Special Forces combat divers an edge. And, it was definitely a challenge for me to overcome those natural instincts to pass dive school.”

The US Army utilizes its divers as individuals who have been vetted an additional step beyond the traditional Special Forces vetting process. “Many times, dive teams are the go-to teams in the company,” Paul explains.

He received additional training as a dive medical technician, or DMT. “I would go on dives with the guys, but I would also support the dives medically. Dive injuries are generally catastrophic when they do occur, so having adequate medical coverage is key to sustaining a safe training environment and minimizing the risk factors involved.” Paul would be the medic prepped to administer a neural assessment if needed.

Back with his home unit, he continued to train with unit doctors and physician assistants. He also helped conduct team training with combat casualty case scenarios. “We continuously strive to improve all of our individual skill sets,” Paul tells us. “We do this to make sure that, if one of us is injured, we can carry on for one another and pick up the slack left behind by the absence of a team mate”

The other reason to train the team is for the possibility of a mass casualty event.

“If I’m the only medic on the ground, I can ask these guys to assist me,” Paul says. With enough preparation, the team would be savvy enough to automatically know their role in a stressful medical situation. “Ideally, I wouldn’t have to explain everything to them as we go. No one wants the first time they need to use a particular skill set to be under fire from the enemy.”

During his tour in Afghanistan, Paul realized the importance of face-to-face contact with the local populace. “We’re here in their country, they have been told stories about us,” says Paul. “Having direct contact with the local people shows them you’re not as bad as the enemy tries to advertise you to be. It upends the dehumanizing factors that can separate people.”

It works the other way as well.

While traveling through the Afghan countryside, the Special Forces team is aware of IEDs placed everywhere that are meant to kill. “You can begin to foster the mentality that everybody is out to get you,” Paul says. But while incorporating yourself into the local populace and contributing to the health of a village, you can start to become more of a friend to the populace than the enemy that lives there. Additionally, you see their humanity laid out before you and they can see your compassion.”

“Those realizations helped guide me along this path that I’m on now,” Paul tells us. “I feel like a lot of the problems that we face in the world today come from stratification and lack of interaction between countries and peoples. We even see it here in the United States politically and in other ways. By isolating ourselves from one another through lack of communication and misinformation, divisions take root. Providing medical treatment and building medical infrastructure and education are just some of the ways in which those gaps can be bridged.”

Paul explains that an 18-Delta combat medic is accustomed to “sticks and rags” medicine. It’s broad-based knowledge, but missing many of the specifics one obtains from work in hospital environment as opposed to the field.

“I want to be able to be more of a professional healthcare provider and know what right looks like from a modern first world perspective. I want to be proficient and really learn medicine to a higher degree than I’ve ever known before. So, becoming a PA seemed like a good transition for me.”

This line of thinking was prompted in part by a drawdown in military presence in Afghanistan, and the initial pull out of Iraq. At the time, there was a sense of the United States going to a peacetime military rather than a war-time military stance.

“That feeling I had initially when the war started? That was going away. My purpose was going away, and I just didn’t want to practice just to practice, you know. That was a big contributor to my getting out.”

When Paul did get out, the transition to civilian life proved to be much more complicated than he would ever have imagined. Without a wife and kids, Paul found that he was pretty much married to the military. Getting out was a shock to the system.

“After eleven years, I had a lot wrapped up in that identity,” he says.

He became a member of the Washington National Guard but the question of identity remained front and center. “I didn’t even realize it was a problem at first.”

He talked it through with family and others who had made the change before him. After significant soul searching, he decided that becoming a civilian PA was similar enough to his military work as to hold the promise of meaning and satisfaction for him.

“As 18 Deltas, you have a lot of decision-making capabilities and responsibility thrown on your shoulders,” says Paul. “So, I felt that being a civilian PA would be a logical progression from that.”

Paul researched and applied to a handful of PA training programs, but MEDEX Northwest became his focus, as it “had a great reputation” and seemed best aligned with the general mission of his work in Special Forces. “Also, I wanted to stay here in Washington State,” he admits.

Once he was notified of his acceptance to MEDEX Northwest, that was it. He cancelled all his other applications.

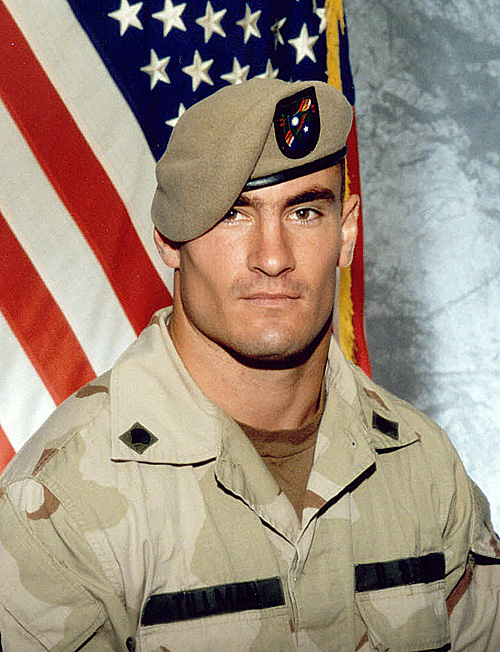

Currently in his didactic year at MEDEX, Paul Hastings was named a 2017 Tillman Scholar by the Pat Tillman Foundation for his commitment to continue his service through medicine.

In 2002, Pat Tillman left a successful football career with the Arizona Cardinals to join the US Army. He was killed in Afghanistan in 2004. Family and friends created the Pat Tillman Foundation in 2004 to honor Pat’s legacy and to pay tribute to his commitment to leadership and service by building the leading fellowship program for military veterans and spouses.

Paul received a $10,000 annual scholarship to support his education as well access to professional development opportunities including the exclusive, annual Pat Tillman Leadership Summit powered by the NFL.

Paul recalls the impact of hearing about Pat Tillman’s death during his first duty station in Korea.

“I was eating breakfast when we learned Pat had been killed. Everybody knew who he was because of his reputation for having walked away from a lucrative contract in the NFL to go and serve his country. The fact that he had made the ultimate sacrifice made an impact on me. His death was both tragic and inspirational.”

Paul recently participated in the 2017 Pat Tillman Leadership Summit. “It was very motivating, intimidating, and really made me recognize the responsibility that I now have to pay this opportunity forward,” he says.

But right now, sitting in the MEDEX Northwest classroom, Paul’s got plenty on his plate. “First things first,” he says. “I’ve learned through experience, it’s important to focus on the 50-meter targets.”

Jumping ahead a bit, we know that Paul will graduate in August of 2019. And after that? He’s hoping to practice broad scope medicine, perhaps in an ER or primary care. Eventually, he has his sights set working overseas, perhaps with Doctors Without Borders or the World Health Organization. “As a Green Beret, one of the things I bring to the table is my work with other cultures.”

Paul is clear on the contributions of former military personnel as leaders.

“There’s a lot of potential among veterans, especially with soldiers that have served in combat,” he says. “There are a lot of great leadership skills, a lot of great experience that can translate directly over to the civilian world. Although some other skill sets translate better than others, PA is one of those instances where it does. I want to urge guys who are making the transition, and let them know that there are opportunities out there, sometimes it just takes some searching to find them. There are a lot of stereotypes against combat arms soldiers coming back—that everybody’s got PTSD, guys are broken, stuff like that. While, those experiences definitely do change guys, the growth that can come from working through those experiences offers many strengths and perspectives that can help society grow as well.”

MEDEX Northwest is proud to have Paul Hastings as part of our team. He stands in a long line of US military veterans who have been essential to the PA tradition from its very start.