All graduates of physician assistant training programs must pass a certification exam before they can practice in their new profession. In the United States, the certifying body is NCCPA—the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Many take the national test—the PANCE, or Physician Assistant National Certification Exam—right out of PA school, others in the months that follow graduation. Once they register for a PANCE session, graduates report to one of any number of regional testing centers to take the exam. All testing is done using secure computers.

In quick order, the test results are known and reported back to NCCPA, the student, and the educational institution. It’s a simple pass/fail. Those who pass can add the credential PA-C (for certified) after their name, and begin their careers as physician assistants.

But for those who fail the PANCE on their first attempt, life gets a bit more complicated. NCCPA requires that they wait at least 90 days before they attempt the certification exam again. That’s 3 months added to the previous 27 months spent fulltime in studies. For most, this has meant foregoing 2+ years without earning an income, focusing all their resources on their education and a future profession.

For educational institutions, particularly those with high first time pass rates, news of one of its students failing the PANCE test is not taken lightly. In part, this is because it is a matter of public record. In the interest of transparency, NCCPA requires that the cumulative first time pass rates over five years be clearly visible on the institution’s website. For MEDEX Northwest, this information appears through a link in the footer of every page: https://familymedicine.uw.edu/medex/cms/wp-content/uploads/NCCPA-Accreditation-Pass-Rate-2016.pdf

The most recent PANCE records from the 2015 graduating classes see MEDEX Northwest at a 93% first-time pass rate. In contrast, the 2009 MEDEX scores were as low as 79%. What could account for this 14-point rise in the MEDEX first-time pass rate over six years? And, perhaps more importantly, what was behind the all time low?

Facing The Challenge

First, it’s worth considering the certification exam itself, which “has gotten increasingly more difficult over the past 10 years,” according to Scott Massey, PhD, PA-C, a national expert on PA education. “It’s become more and more academic. If programs don’t keep up and provide academic preparation for the exam, then the pass rates drop.”

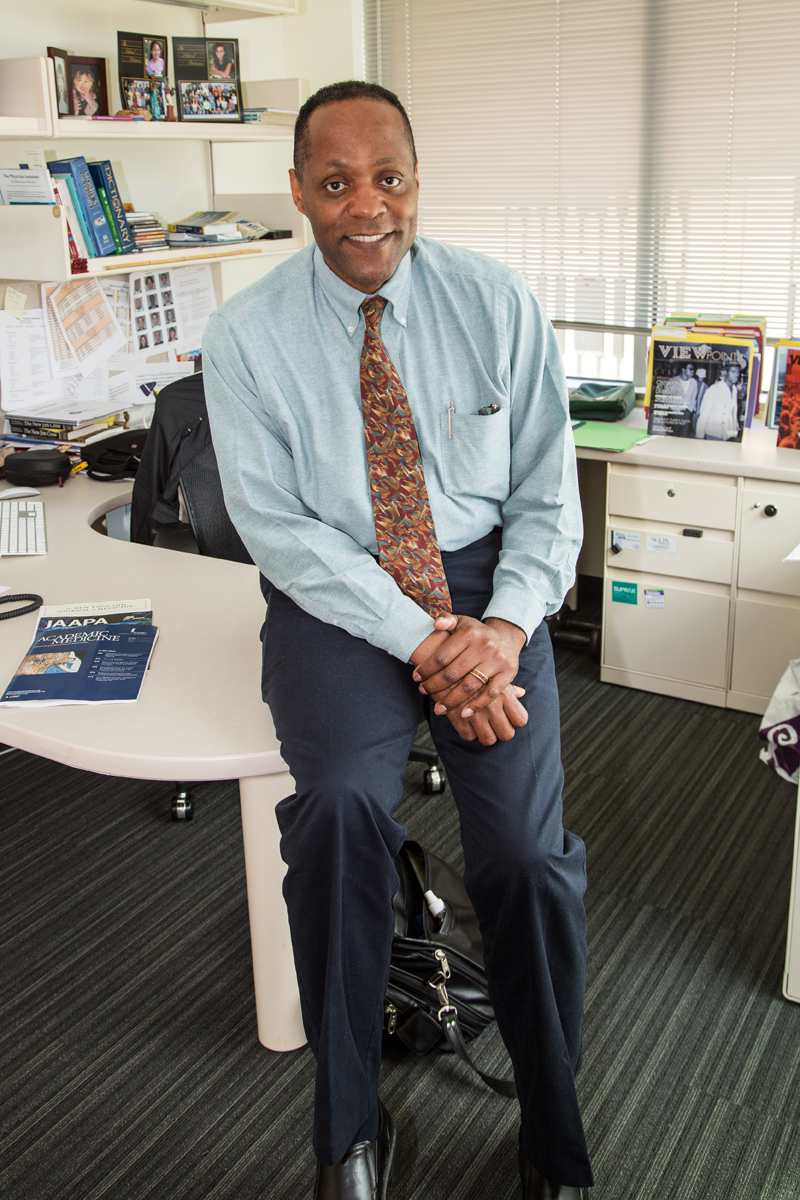

In the face of this, the falling PANCE pass rates served as a “wake-up call,” says MEDEX Program Director Terry Scott, MPA, PA-C. “MEDEX was facing a challenge. We recognized that the PANCE scores had to improve. But they were also a symptom of a greater issue.”

In the face of this, the falling PANCE pass rates served as a “wake-up call,” says MEDEX Program Director Terry Scott, MPA, PA-C. “MEDEX was facing a challenge. We recognized that the PANCE scores had to improve. But they were also a symptom of a greater issue.”

The profile of the MEDEX cohort reveals an older student, averaging around 33 years in age. In part, this is driven by the MEDEX requirement of 4,000 hours of prior patient contact, something most PA schools do not ask of their applicants. Consequently, MEDEX students are on their second or even third career, and often quite a ways down the road from their previous academic pursuits. As a result, many are unaccustomed to the rigorous classroom and learning demands of PA school.

Facing a downward slide in the PANCE scores, there was a tendency to offer excuses based on this typical MEDEX student profile. “Our students are special,” was often heard, or “Our students are older.”

“There were excuses made,” says Terry Scott, “and that just didn’t serve them. We are proud of the type of people we go after. They are mission-driven, but there is no reason that they can’t perform at the highest level on any exam. MEDEX can have a social justice mission, and we can still have high quality academics with the students we choose.”

Scott directed the combined efforts of the MEDEX faculty and staff to both “own” the situation and to remedy it. “We needed to look at this in a very open and transparent way,” he says.

In response, the MEDEX faculty came together in the spring of 2012 for a retreat to discuss the challenge before them. The retreat included a psychometrician from the NCCPA to talk about test item writing. Participants heard firsthand how the NCCPA had moved to more closely align the PANCE exam with the demands of the workforce. MEDEX also brought in the nationally recognized PA education and remediation expert, Scott Massey, PhD, PA-C for advice.

Program Director Terry Scott remembers the 2012 retreat as a “vigorous and boisterous” one. “It was like the uncorking a lot of energy. This was an opportunity to address some of the long-standing issues that we weren’t able to address up until now. We were not going to blame our students. We had to own this. We had to own it as an organization and address the issues.”

In 2014 the faculty came together for another retreat where MEDEX set forth a new vision and value statement for the program: “We work on behalf of our students, the community and organization to make it better.”

Step by Step, A New Approach

Of course, this kind of major change doesn’t come simply, or easily. “This is work that takes multiple approaches, and they all need to be done simultaneously,” says Dr. Linda Vorvick, the former Director of Academic Affairs at MEDEX from 2008 to 2015. “We looked at the problem from both a macroscopic view and a microscopic view,” adds Amee Naidu, MEDEX Director of Student Affairs. “There were so many areas in our program that needed to be changed.”

First, it was agreed that MEDEX had to make it crystal clear to its students that they are expected to study and prepare for the PANCE. This included deciding to purchase and provide the students with online tools to use in practicing and better preparing for the examination.

Next, MEDEX added curriculum in the second year to keep the students practicing their testing skills throughout their entire clinical year. “We gave them practice exams,” explains Dr. Vorvick, “and used our faculty resources, like MEDEX researcher Doug Brock, PhD, to develop metrics that let our students know their likelihood to pass or not pass the PANCE. That way they know how much effort is needed to put in to prepare for the test.”

It was also decided to up some of the prerequisites, so that candidates entered the program with stronger science backgrounds. “We increased the specificity of what kind of science we want to see before people come to MEDEX,” adds Dr. Vorvick.

Additionally, steps were taken to map the MEDEX didactic curriculum to the PANCE blueprint. “We made sure that we were teaching the things that were on the exam, so that the students were made familiar with these concepts at least once in the classroom before they got to their clinical year,” says Dr. Vorvick.

Additionally, steps were taken to map the MEDEX didactic curriculum to the PANCE blueprint. “We made sure that we were teaching the things that were on the exam, so that the students were made familiar with these concepts at least once in the classroom before they got to their clinical year,” says Dr. Vorvick.

This effort would require the assistance of the entire didactic faculty over the course of several years. “It was very complicated,” says Doug Brock, PhD and a researcher for MEDEX. “There was an enormous rescheduling and rejiggering of the didactic curriculum. Linda Vorvick gets a lot of credit for the restructuring of the curriculum to better meet what the modern needs are. We had a curriculum that was truly out of date in terms of how it fit with the profession, what the profession saw as important to measure.”

The new understanding emerged that MEDEX would have to look at what the PANCE is testing for, accept that this is how the profession is defining competency, and determine that they would have to teach to that.

All of these changes forced nothing less than an upheaval in the school’s educational objectives, and had to be made while staying true to the new MEDEX vision and value statement that emerged from the retreat.

Dr. Linda Vorvick believes these efforts all combined to bring the PANCE rate up over the course of six years. “There is no one particular thing that made the difference”, she says.

Testing To Determine Who Needs Assistance

Since 2012, these efforts have focused on the PANCE examination itself. “We’re preparing our students—our at-risk students—for the PANCE exam,” says Naidu. “We prepare all students, of course, but we’ve identified data that helps us narrow down the students who need a little bit of extra help to pass the exam.”

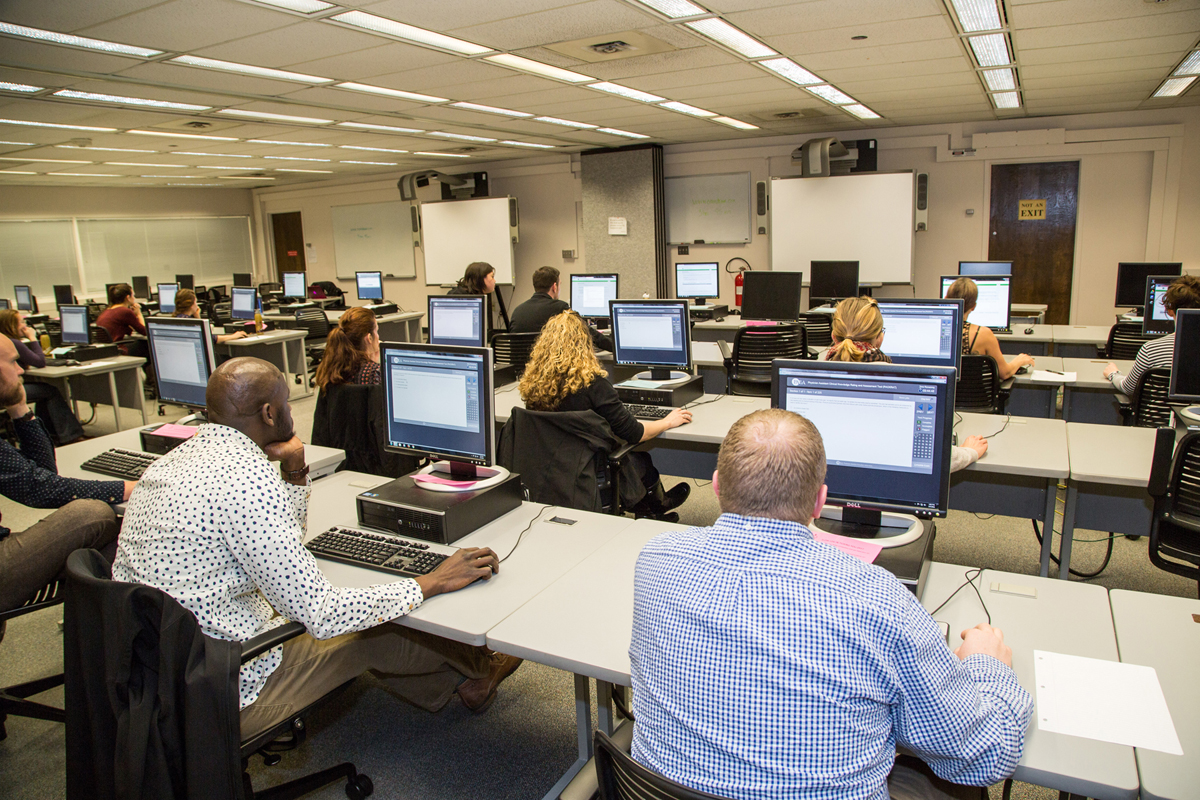

The process of determining which students might need assistance begins in December of their didactic year with a national test called the PACKRAT I, short for Physician Assistant Clinical Knowledge Rating Assessment Tool. “And it’s online, they get the results right away,” explains Naidu. The students’ scores are compared to all others from across the nation, yielding solid stats on these peer-reviewed questions. “It’s basically a practice test for the PANCE,” says Naidu. “It’s an indicator: if they score above a certain amount or below, we know how they’re going to perform.”

In January/February of their clinical year, MEDEX students return to their home site classroom for Campus Week. At that time they take their second national practice exam, the PACKRAT II.

The PACKRAT II exam is used to generate a predicted PANCE Score. Those students who have a predicted PANCE score below 400 are contacted by Amee Naidu, and they begin remediation. Typically, she begins by asking the students to write ten test questions per week especially on their weaker topics. “Test question writing is a great way for students to enhance their critical thinking process,” says Naidu. After repetitively utilizing this method over weeks, students notice a difference in the amount of medical information that they understand and retain. “These sorts of remedies can make a big difference”, reports Naidu, as evidenced by seeing struggling students, who were predicted not to pass, go on to achieve their certification.

Custom Testing

Then again in December, the clinical students return to their campus to take what’s called a Formative Exam. Essentially, it’s a custom PANCE practice exam developed by Scott Massey, PhD, PA-C, to help identify those students who could be at risk for failing the certification exam. In 2012, MEDEX engaged the services of Massey and his supplementary testing methods, which he built from his research with 1,500 PA students over eight programs across 10 years.

These practice exams—called the Summative One and the Summative Two—are large 700-question tests administered to all MEDEX students during their clinical year while they are assigned clerkships out in the field. Doug Brock crunches the data from the Summative exams. “I define at-risk status as a greater than 20% chance of failure on the PANCE,” he says. “In our worst years we were hitting estimates that 30 to 35% of our class were at risk.”

Scott Massey has some thoughts on this. “A lot of PA programs struggle with this because, in the clinical year, the students have to study independently,” he says. “They don’t have the structure that they had during the didactic year, and some students just aren’t able to keep it together along with all of the responsibilities they have going on at their clerkships for that second year.”

Massey is the first to admit that his tests are not the perfect instrument. “But based upon the blueprint that is used for the certification exam, I believe that if you create some testing instruments that simulate that exam closely enough that you could track scores. And using some statistics like regression, for example, we can actually generate predicted scores or at least look at ranges of potential scores that a student would potentially achieve if they did not have intervention.”

It’s about obtaining feedback on the students and their academic progress. For the students identified by the Summative One and Summative Two as potentially at risk, the prescription is to provide more robust mentoring such as test-taking skills, study skills, individual counseling and remediation during the clinical year.

Remediation Efforts

Over the years, MEDEX has deployed remediation in different forms, most often in the form of retesting. Yet according to Doug Brock, MEDEX was remediating students “who maybe needed just a bit of time and a bump, while we were missing students who were consistently scoring low but passing.” Brock’s application of Scott Massey’s testing methods and the subsequent research revealed a better understanding of the particular challenges at MEDEX.

As a result, there was a new effort surrounding remediation, which was led by Amee Naidu. In this instance, remediation means something specific. “It means training our students who are struggling to learn medical information by giving them the tools necessary to build their critical thinking skills so that they can take examinations better and pass their PANCE exam,” she explains.

Naidu isn’t a fan of the terms remediation or at-risk. “These are struggling students,” she says. “The course that I promote to them is the PANCE Skills Course. It’s designed to enhance critical thinking skills.”

Individuals with passive learning habits are often challenged by PA school and the requisite testing. Naidu believes critical thinking skills are essential for any practicing clinician. “When patients visit the clinic, they’re not going to say, ‘My situation is described on page 37, look me up.’ They come in with extra variables—they have several symptoms—in addition to complex personal lives. On the spot, you have to pull together 5 to 10 pieces of information, and come up with a solution. If you’re a passive learner versus an active learner, when you go into the clinic, you will not be able to pull medical information together and come up with a solution. It’s the same thing for the PANCE exam.”

Naidu is the first to say that being good at testing is not necessarily the measure of a good clinician.

“Countless times with our struggling students, I see their bedside manner and their approach to patients as just phenomenal,” she says. “I would send family members to them once they are practicing. Students are often surprised to hear this but are also encouraged. In my mind, being a good PA is not just about being good in academics.”

“Countless times with our struggling students, I see their bedside manner and their approach to patients as just phenomenal,” she says. “I would send family members to them once they are practicing. Students are often surprised to hear this but are also encouraged. In my mind, being a good PA is not just about being good in academics.”

Doug Brock stresses that the PANCE is strictly an academic measure. “It doesn’t measure skills,” he says. “There was also always this disagreement about whether or not it was even important to focus so much on the PANCE, which is both a very good question and one that is a little frustrating. Because passing the licensure exam is a necessary hurdle to being able to practice as a PA. But I don’t know anybody, myself included, who thinks that the PANCE is necessarily a strong indicator of clinical proficiency or later skill or value in the workplace.”

Naidu continues: “To me, sometimes the struggling student has a little more humanity, so long as they’re safe. As a PA, you have to know when to ask questions and know your limitations. But for sure, with guidance, struggling learners can fulfill this mission and go on to become successful PA’s.”

Often, these deficiencies come as a surprise to the student. After all, they have to be very high functioning to be selected as one of the 130 students from among the 1,200+ applicants to MEDEX each year. Students find that even though they studied hours for course exams, it may not be reflected in their scores. “But now it’s at a new level,” says Naidu. “They’re learning a lot of information all at once. They’re taking several classes. There’s a lot of peer pressure, and they don’t have enough time to digest the material because they’re in class all day. On top of it, they have additional responsibilities at home.”

All the students that are not doing well will end up working with Amee Naidu. When Naidu makes her assessment, she’ll often discover some studying or concentration deficiency. “They’d been getting by, but they’ve not been studying correctly this whole time,” she says. “Now they have all these major, hard core medical courses, and everything comes out. The students may be assessed with poor organizational skills, poor executive functioning skills, test anxiety, or they’re just having difficulty coping with the pressures of PA school.”

During her individual assessment session, Naidu talks with the students to see what they need in order to succeed. “Sometimes we refer them to Accommodations DRS (Disability Resource Services) or to Intermediate Studies Strategies. It’s this latter effort that Amee Naidu leads. It starts with individual counseling, and there’s the PANCE Skills Course that Naidu developed over a year’s time.

It’s a self-directed course built in three different plans—13-week, 18-week and 32-weeks. Depending on the individuals and their needs, she’ll recommend a study plan of specific duration. The course then becomes available to them through Canvas, a proprietary web learning management system or LMS.

An Option For Uncertified Alumni

This is all well and good for students currently enrolled in MEDEX. But what of those who have long since graduated from MEDEX, failed the PANCE once, maybe more, and are not yet certified to work in the profession in which they trained? After all, there is a limit on the number of times they can take the national certification exam and fail. After six failed attempts or six years, NCCPA rules require that they reenroll in PA school.

Naidu was given the additional job of reaching out to these former students and offering them the PANCE Skills Course. “Some hadn’t been able to pass the exam for a couple of years. They were all struggling.”

“I knew they weren’t going to be happy with MEDEX contacting them after all this time,” says Naidu. “They were going to be upset and suspicious of our efforts.” Many had returned to their old line of work in the absence of a PA certification.

“I knew they weren’t going to be happy with MEDEX contacting them after all this time,” says Naidu. “They were going to be upset and suspicious of our efforts.” Many had returned to their old line of work in the absence of a PA certification.

For these former MEDEX students, Naidu has developed an additional study tool kit. She refers to it as a feel-good gift containing various items useful for effective study habits: a planner, notebooks, post-its, a dry-erase sheet and more. Together, these items were meant to engage the individual in the process of studying.

For those who accept help, these former students from across the 5-state WWAMI region can logon to follow the self-directed courses, week by week. The onus is on the individual to check-in with Naidu on a weekly basis to receive direction and counseling. Naidu suggests personal rewards for every study milestone achieved.

The rigors of the course can prove overwhelming for some. “Because it requires 8 to 10 hours training a day, some just can’t struggle through it,” says Naidu. Anyone who has applied themselves to Naidu’s course has realized success, but it demands commitment and regular communication. “Some people start on the course, and they’re supposed to check in with me regularly. Later on, I’ll find out they failed. But I didn’t know they took the exam or I would have told them, ‘No way, don’t take it.’”

In working with Amee Naidu, Doug Brock finds a lot of hopefulness for these graduates who remain uncertified. “She is doing some things which are unique in the profession,” he says. “She’s is doing things that nobody has even thought of. She has a willingness to work with people who have failed the PANCE. And most programs, whether it’s for good reasons or poor reasons, once you’ve graduated, they don’t want to see anything but the back of you. Her actions send a message that MEDEX actually really cares.”

In the past there were concerns from students that remediation was somehow punitive, and that the program was picking on them. “That’s sort of disappearing or becoming less pronounced than it was, which is good news,” say Brock.

A Moral Imperative

Scott Massey holds a unique perspective on all of this. As a researcher, an educator, and a four-time PA studies Program Director, “I was the one that often worked with students that didn’t pass the certification exam,” he says. “I saw the pain, the agony that students go through when they didn’t pass. And I started to think, ‘How could I intervene?’ Which really was the beginning of all this. It’s really about preventing failures.”

Massey talks about the education of physician assistants as two parallel processes.

“You’ve got their holistic education, which involves all aspects of their competency,” he says. “We’re talking about forming them into clinicians through their experiences—academic, didactic and clinical. As their clinical and interpersonal skills evolve, you get a student that emerges as this polished clinician. That’s one arm of it.“

“The other arm of it is, like it or not, we’re teaching to the test. I understand the controversy. I’ve heard that argument a number of times, and some people don’t like it. But I’ve been the one that’s sat with many students that fail. And so I kind of have a sense that, yeah, I know the whole argument about teaching to the test.”

For Massey, programmatic changes assure that schools will not see their students fail the PANCE. “You don’t want to have that happen because once they fail, the stats on that are not very positive,” he says. “When people fail the first time, the second time pass rate goes down to 50%. And if somebody fails a second time, it goes down to about 20%. So you have to capture them during the program.”

“To me, it’s a moral imperative to ensure that they pass,” he adds.

“To me, it’s a moral imperative to ensure that they pass,” he adds.

Doug Brock agrees. “Amee and I both hold this philosophical belief that if you accept somebody into PA training, you’ve already conferred upon them an expectation that they can succeed. The program holds a lot of responsibility for failure at that point, not just the individual. Of course the individual is responsible to an extent, but the program is also responsible to help where help is needed.”

With the most recently available first-time PANCE pass rate from the 2015 graduating cohort at 93%, Doug Brock is encouraged that all the concerted efforts by MEDEX are showing real results. “This past year we had our first uptick, which is actually indicative of a change versus some sort of random fluctuation,” he says.

Today, Scott Massey is the Director of a new PA program at the State University in Pennsylvania. His education research work continues, and his contributions to MEDEX are pro bono. “I know many of the faculty at MEDEX, and I consider them to be colleagues,” he tells us. “I’ve enjoyed working with them, immensely. It made my day or made my week when Linda Vorvick would come to me and say, ‘We’re seeing results.’ That, to me, is what it’s all about. It’s that people, maybe three years ago who might have not passed the PANCE, today, some of them are passing. That makes it all worth it.”