We’ve asked many MEDEX Northwest students about the roots of their interest in healthcare, about what experiences in life might have led them to choosing this profession. And as one might expect, we’ve gotten a wide range of answers. But no one has connected winding up on this path to becoming a physician assistant to falling from a mango tree as a child. No one until now, that is. Meet Ismail Jatta.

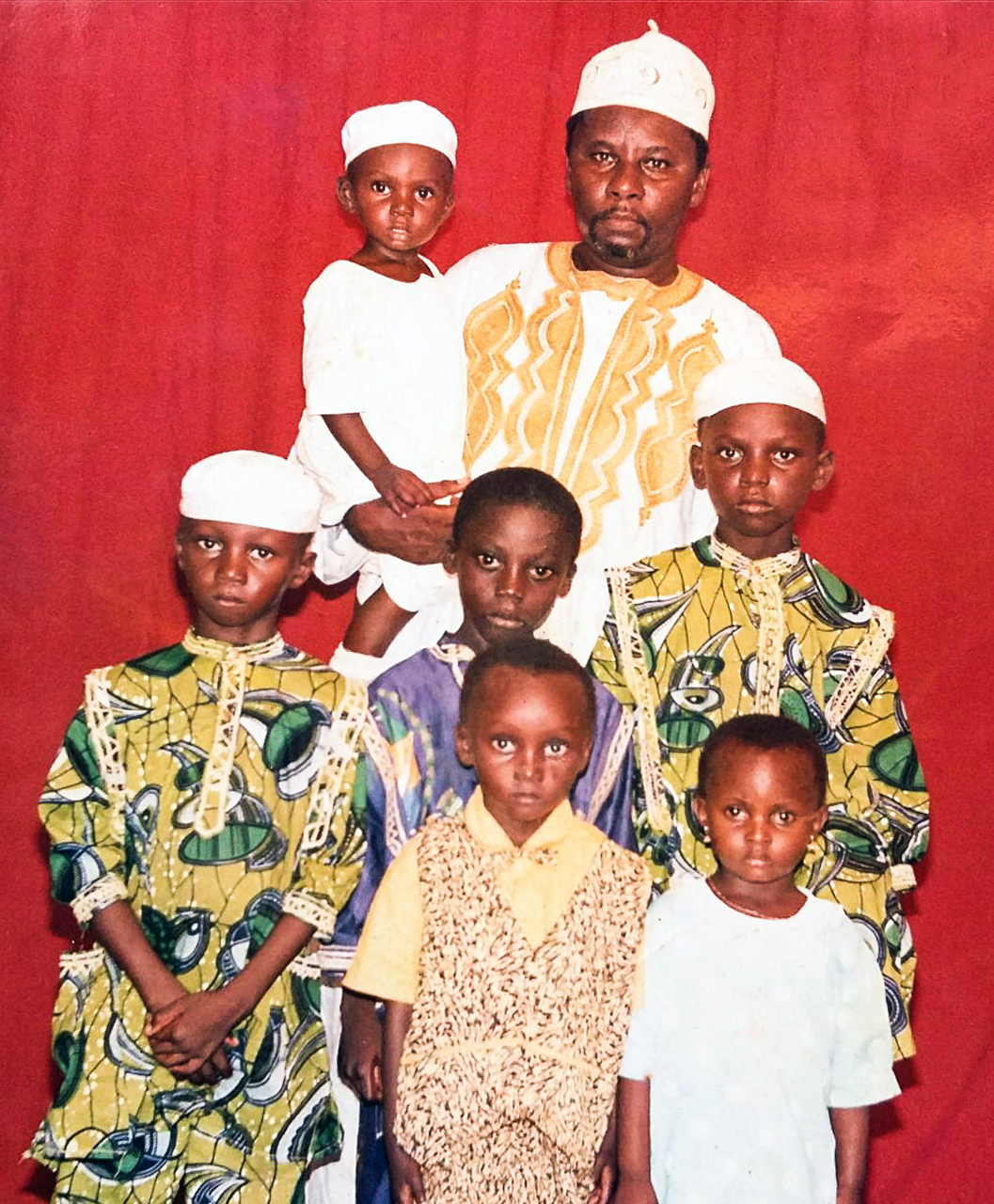

Ismail Jatta is a member of Seattle MEDEX Class 48. Born and raised in Gambia, West Africa, and one of 11 brothers and sisters, Ismail grew up in what he describes as “a household full of people. I’ve always been around a lot of people. There were at least 30 people at my house at any given time.”

When Ismail was 13 years old, he fell from a mango tree near his home, and wound up with a fractured femur. His recovery from this fall was complicated, however, as a result of a misdiagnosis and failed treatment, which led in turn to two follow up surgeries and, ultimately, a dislocation, which he simply learned to live with as he grew into young adulthood.

“I was able to move around on it,” he explains. “I managed to play soccer, I played on the basketball team, I ran track on it. I did whatever a normal kid would do. But I just knew that that I could have been doing more physically than I probably was.”

Thinking on it further, Ismail figures that having that injury at such an age—not being able to interact in quite the ways he might have otherwise—had effects that went beyond just the physical.

“I think it made me adjust to a different level of understanding human interaction, you know? It opened my eyes to what it means to be disabled, for one. Being appreciative and thankful for the little things we take for granted. I think I started learning that at a very young age.”

“I think it made me adjust to a different level of understanding human interaction, you know? It opened my eyes to what it means to be disabled, for one. Being appreciative and thankful for the little things we take for granted. I think I started learning that at a very young age.”

Ismail had always been interested in the sciences, but those early experiences opened his eyes to the medical world. “That basically is where my aspirations come from in terms of medicine,” he says. “I wanted to help people and take care of those in need.”

Ismail’s first opportunity to work and assist other people in a medical setting arose in 2001, when he came to the United States with the intention of attending college. Financial and immigration complications delayed his start, however, so he “picked up” a job as a nursing assistant in a Seattle-area retirement home. After a few months there, he then moved to Everett and took another nursing assistant job, this time at Everett Rehabilitation and Care Center.

After about a year of working as a nursing assistant, Ismail’s knee was becoming a problem he couldn’t ignore any longer. “I was struggling being on my feet 8 hours a day, some days 16 hours straight,” he says. “I knew I needed surgery. I worked a lot of hours so that I could save up money to pay my bills during the time of recovery from surgery.”

Three months after successful knee surgery was performed at Group Health, Ismail took a job north of Seattle, working with the Washington Department of Correction’s Sex Offender Treatment and Community Protection program.

“A lot of the individuals that I worked with had developmental or mental disabilities,” he tells us. The majority of his clients were registered sex offenders living in-group under mandatory supervision. “We had to supervise all of their activities to make sure their environments were safe for them and for the people that are around them.” The job entailed assuring that the clients were abiding by all court guidelines and restrictions. This could even extend to the TV programs that they watched, the books that they read, and going out into the community to shop.

It was during that Community Protection job in 2004 that he reinjured his leg. While supervising the clients as they played basketball in a driveway he slipped and fell. Ismail’s tibia broke at the attachment point of the earlier surgery, so for three months he wore a leg cast from hip to toe.

In 2006, Ismail took a job with the Fircrest School in Shoreline, WA, just north of Seattle. Fircrest is the only state Residential Rehabilitation Center (RHC) located in the Puget Sound urban corridor. While there, he worked mainly with individuals with developmental disabilities, the majority of whom were teenagers.

“Many of them are autistic, though I have worked with children with all sorts of other developmental disabilities,” he says. “I’ve helped a few kids with bipolar disorders and fetal alcohol syndrome.”

There’s one that sticks out the most in his memory—a girl diagnosed with Sanfilippo syndrome, a rare metabolic disease. Those who are diagnosed with it do not live past their teen years. “They have deteriorating mental illnesses beginning in early age with Alzheimer-like symptoms as they grow, to the point where they do not remember or recognize their own family members,” he says.

We wonder what sort of training one needs to work with community protection programs, or at institutions such as the Fircrest School.

“To work with the sex offender population, they hire people off the street with minimum high school diplomas, though some of my co-workers had their bachelor’s degrees in psychology and sociology,” he tells us. There is a brief training, maybe a week, on therapeutical options for supporting these clients, and then you get placed. “A lot of it then comes with on-the-job training.”

At Fircrest, it’s the same kind of minimum requirement: a high school diploma and placement. Some of the jobs there require nursing assistant certification, and that’s what Ismail had when employed there although his credentials were not part of his job requirements or responsibilities.

We ask Ismail to look back and consider what drew him to working with these populations and in such settings, and what it has meant to him in terms of his professional development.

“A lot of it has to do with personality,” he says. “You have to be willing to help these folks. I felt like I had no clue on what to do in a lot of these situations after the training. But my patience over the years with my own issues—dealing with injuries and disabilities—I would say I’ve learned to be patient.”

“You know, patience is not something you learn one time on a degree or fulfill your responsibilities to be patient. It’s a lifelong training. It’s a lifelong process. It’s dynamic, I guess is the short way to put it, it’s dynamic. You grow, you learn. I’ve grown a lot. These guys taught me a lot about myself, in terms of persistence and perseverance—learning to be patient.”

While working fulltime at Fircrest, a job which brought with it some amount of tuition assistance, Ismail finally began pursuing the dream that had brought him to the U.S. in the first place: earning a college degree. After taking a couple of courses at Edmonds Community College, he transferred to Shoreline Community College in 2007, and then transferred to the University of Washington in 2009, where he earned a B.S. in Biochemistry in 2012.

“Initially my goal was to go to medical school,” he says. “While at the University of Washington, I had even registered to take the MCAT and planned to apply to medical school. But then, this idea of being a physician assistant came along.”

Over the years he had encountered PAs in various settings. While completing his bachelor’s degree, Ismail had a long conversation with a friend who was enrolled in MEDEX. And after his knee surgery in 2004, the provider that he followed through with was a PA in orthopedics.

Exhausted after receiving his undergraduate degree, Ismail took a step back. Did he really want to pursue medical school? Really, all he wanted was to take care of people. And in this conversation about PA school Ismail and learned that he could still take care of people as a provider without having to go down a 7-year academic path.

Ismail applied to MEDEX Northwest right after graduation, but he was not accepted the first time around.

“I went back and did a lot of homework, you know,” he says. “I studied the profession and did a lot of shadowing of PAs. It gave me an opportunity to really prepare and learn about myself. So I grew.”

The second time around, Ismail Jatta was accepted into MEDEX, and joined he Seattle Class 48. As it is for most, Ismail’s first year of study in MEDEX, the didactic year, proved to be intense.

“I don’t think you can ever be prepared, although we were warned before coming in that we have to be prepared,” he says. “But it really hit me. I had to adjust. I found myself waking up one night in the middle of the night kicking the wall! That was during the most challenging part. But then, with my experiences, I knew if I took a step back and looked at the journey—looked at how far I had come, looked back to where I once was—then I was able to refocus, and make all the adjustments that I needed to make in terms of studying, note-taking, group studying. I really adjusted. Then I just took care of everything as I had to.”

Now, as he finishes up the clinical rotations well into his second year, Ismail appreciates most the “willingness to teach” that his preceptors have brought to him. He speaks highly of their abilities “to enable and enhance the learning experience. They’ve allowed me to learn, grow, polish my clinical skills, strengthen my understanding of medicine itself, and of patient care.”

With graduation and certification now within sight, we wonder where we should look for Ismail Jatta in the years to come? “I don’t look too far ahead,” he answers.

“My experiences have taught me differently. I don’t worry too much about the future. I mean, I know things are just going to play out as they are meant to be. Things are always going to be as they are meant to be. This has always been my belief. But I see myself in the future taking care of people, especially those that are really in need— to do the best I can for them.”

And does he ever hear Gambia calling out to him to return?

“Gambia is always on my mind,” he says. “Gambia is my home. Gambia is where I came from, you know? If I am in a position to go back and give what I can to that community, I will do that. Whether it be to volunteer, whether it be to settle down … eventually.”

“I don’t know if that plan is going to play through, but that’s always a plan—to be back there, help those in need, help contribute to the national development and contribute to the growth of healthcare in the country. You know, I always want to take care of the Gambian people. I think that is always at the back of my mind every day, night in, night out. I don’t know when that would happen, but it’s always on my mind.”