After 29 years as program director of MEDEX Northwest, Ruth Ballweg stepped down from that role in 2015 and retired from the University of Washington in March of 2016. She is now Professor Emeritus in the Department of Family Medicine. Over the course of three decades, Ruth has had an indelible impact on the physician assistant profession. Here she talks about some of the challenges of that career, and what she sees ahead for herself and the profession.

The Early Years: Struggling To Stay Alive

MEDEX: You’ve recently retired from MEDEX and from the University of Washington. You’re now a professor emeritus. This comes after how many years of being a PA? And how many years of being the section head/program director for MEDEX Northwest?

Ruth Ballweg: Well, I graduated in ’77, so that tells you how long that is—a long time ago. I joined the faculty in ’81, and became the director in ’85. So 29 years as a director, 33 years as a faculty person.

MEDEX: Longer than anyone really.

Ruth Ballweg: Yes, it’s an unusual record. The only reason I probably did it that long is I remade my job every year. There was always some new crisis to be dealt with.

MEDEX: This included the very survival of the program in the early days, right?

Ruth Ballweg: Exactly! It was frightening, and that was not just true of the MEDEX program alone. Believe it or not, we didn’t get Medicare reimbursement for PAs until 1995. The first PA program was at Duke in 1965. So it was 30 years from the time of inception until we could participate in a standardized reimbursement structure. And until that happened, we didn’t really feel totally legitimate. Both PAs and NPs felt we could be wiped out by the stroke of a federal pen.

MEDEX: Why was there so much resistance?

Ruth Ballweg: First of all, this is a federated government. Every state had its own laws. And it had its own insurance commissioner who could decide what reimbursements were. And just like today, some states are more progressive and some are more conservative. Based on that, some state medical associations were more progressive or more conservative. Fortunately, the Washington State Medical Association was an early leader.

So a lot of it had to do with the tone and support of the medical association moving ahead with licensing and then prescriptive privileges. And then finally there needed to be a national standard for reimbursement.

Medicare was passed in the late 60s. Before that, PAs were reimbursed at 100%, 70%, 30% or not at all. It all depended on the insurance company. So Medicare decided on 85% for both groups—physician assistants and nurse practitioners. And this was fair for a variety reasons. That also meant that the doctor did not have to see the patient—85% without the doctor seeing the patient. This meant PAs and NPs situated in remote areas by themselves no longer were party to an inefficient system. So it that took that long, and we were all terrified much of the time.

And then in 1982 a federal report came out that said that we had too many doctors. That’s when the federal money went away, or we got decreased to about half. It was very frightening.

MEDEX: How did it happen that there was a federal report declaring too many doctors?

Ruth Ballweg: Well, there was something called the Graduate Medical Education Advisory Committee [GMENAC]. And they decided there were going to be too many doctors, based on their data. By the way, this happens all the time in other countries and it’s never correct. It’s never a correct prediction.

In this case, the reason they made the mistake was they didn’t realize that more and more women were going into medicine. These women didn’t want to work the 90 hours that private doctors were working, all of whom were running their own business. The women wanted to be salaried, they wanted to work part time. Which, by the way, was still 40 to 50 hours a week. And so that meant they weren’t the same number.

Soon the male doctors followed suit. They said, “We don’t want to do that either.” So when the Feds thought they’d have too many doctors, it turned out that we didn’t have enough, and then the pendulum swung back in our favor But in the meantime, the infrastructure and the funding was wiped out, and every individual PA program struggled with how to stay alive.

Fortunately, as PA program directors, we all held hands while struggling to figure things out. We could’ve become adversarial, but instead we became collaborative and that was a good thing.

MEDEX: What year are we talking about, and how many programs were around at that time?

Ruth Ballweg: This was the mid-80’s. There were something like 50 PA programs. MEDEX was the only one in the entire Northwest. There weren’t any in Oregon, and nothing in Idaho. Later, I was a consultant to all of those developing programs. There weren’t as many programs in California. There was a huge concentration of them in New York, Philadelphia and Boston, just like there still is today. But there really was a shortage. There were a number of states that had no PA programs at all.

MEDEX: Was there anyone in particular who was mentoring you through this?

Ruth Ballweg: My mentors were doctors. John Coombs was one. Dick Layton was another, and Dick Smith another. If you reached out to them, they were there. But they were busy, too. There were no women mentors at all. And women doctors, there were no women physician leaders at that time in medicine, and certainly not in family medicine. It was incredibly lonely.

Moving The Program To The UW School Of Medicine

Ruth Ballweg: At that time MEDEX was in the School of Public Health. We didn’t have roots in the Medical School at all. Back then we didn’t know anybody in the Medical School, and they didn’t know us.

Under the leadership of Dr. Dick Layton [the Family Medicine Residency Director at Providence Hospital and a leader in the Washington Academy of Family Physicians], we had a physician advisory board, which included doctors from the medical school, CEOs of big hospitals and representatives of the Washington State Medical Association. This was a powerful group that Dick had put together. They met regularly, probably quarterly, and they supported us in getting preceptorships and getting press coverage. At that time, the clinical year was just under one doc only. But that changed in the early ’80s.

This advisory committee actually vetted all the preceptors for the medical students. And that was all based on the idea that the medical association felt that they were the joint sponsors of the program along with the Medical School. They had an obligation to see that it went well. That was great. We’re talking the 80’s here—probably 1985 to 1995, until we moved to the Medical School. This was the first ten years that I was program director.

During that time we started seeking out some other sources within the advisory board to move the MEDEX program away from the School of Public Health, because we felt there wasn’t much support for us there. Actually, they just started treating us with benign neglect. If they could take credit for us, they would, but they really didn’t want to get involved in any hassles. And they didn’t really have much contact with the medical community. And they still don’t, compared to the School of Medicine.

MEDEX: What were the strategies to get under the sponsorship of the UW School of Medicine?

Ruth Ballweg: We had a group of people working on that. Dick Layton was working on it. We actually went to the community colleges, he and I, and met with the presidents of North Seattle and Seattle Central Community Colleges. We were exploring the idea of moving the MEDEX program there.

The good news was that within the UW School of Public Health we had self-sustaining status. There were five self-sustaining programs within the University. With an early 1980’s budget crisis in Washington State and at the University of Washington, these five programs (from the School of Public Health –including MEDEX, the School of Business, and the School of Engineering) were granted this special status to allow us to grow and prosper in difficult times. This status meant that we could begin to create an infrastructure and build some reserve funds. This was particularly necessary when federal money went downhill.

Then, what happened was the Board of Regents hired Pepper Schwartz in a special capacity. As a UW Professor of Sociology, she was also a nationally known expert on sexuality. They hired her for two years to make more women visible in leadership roles in the University. Part of that was to invite people to come and talk to the Board of Regents, so she invited me. Next thing you know I’m talking to the Board of Regents about what the MEDEX program is doing in Alaska. And Mary Gates is there, mother of Bill Gates. I’m talking and she’s giving me all this positive body language. I mean you could just feel it. Afterwards I get a call from the Dean of the Medical School, who was chair of the Medical School Executive Committee. He said, “Mary Gates has asked that you present that same talk to the University of Washington Medical Center Board of Directors.” And before that meeting was over, that group had decided that MEDEX should move to the medical school. After all the work that we had done, it was just a matter of being in the right place at the right time.

The medical school hired a consultant for $35,000 to recommend how we should move into the medical school, and we worked with them for almost a year on all the details. Dr. John Coombs, who just joined the School of Medicine as the Dean of Regional Affairs, was appointed to work with MEDEX as the transition contact.

With John’s advice, we negotiated how MEDEX would fit in—at the highest level—into the Medical School. This included ad hoc representation on the Medical School Executive Committee. Similarly, Jennifer Johnston, our MEDEX administrator, was appointed to the overarching group of Departmental Administrators.

These were unique appointments. Typically, these positions represented clinical and basic science departments and not individual programs. But because we reported to the Dean’s office directly at the same time we were in the Department of Medical Education, it made sense for us to be on those committees. That’s how we began to make MEDEX more visible.

MEDEX: With MEDEX under the School of Medicine, was it easier to obtain funding through HRSA and other federal entities?

Ruth Ballweg: That didn’t change that at all. I mean we were still on our own. We had to learn how to write grants.

When I became the Program Director and Jennifer the Administrator, the first grant cycle was coming up in April, and we had to have a grant written by September 1st. That was 50% of the budget determining whether we keep the program alive or not. I can’t tell you how frightening it was.

But we found some people to help us. And it was interesting, because other PA programs were going through this same thing. They lost their money because of the GMENAC report. It’s a famous turning point, good or bad, in medical education funding in the United States.

All the PA programs at that time might have thought we would compete with each other. But almost all of us were new program directors. There were like 15 brand new program directors. We got on the phone, and all got in cahoots with each other rather than competing. We wrote similar kinds of projects so they couldn’t be turned down. Frankly, we didn’t know what we were doing. But it turned out after that we were friends forever, like blood brothers and sisters. It really created a major strength in the PA education community.

It also happened to be the year my dad was killed in the crash of his air ambulance. So it was one of those years from hell.

The Move To Masters

MEDEX: Let’s jump ahead to another battle. I’m talking about the impending switch to the master’s only program. What was the debate and the struggle around it?

Ruth Ballweg: Well, the debate started with the change to a bachelor’s degree because originally PA programs were certificate programs. The reason for that, I think, is that people wanted to have a pretty wide open door. So many programs were certificate programs, and then they moved to bachelor’s degrees. And that for some of us, felt like the writing on the wall, because we thought once bachelors, it’s going to go to masters.

MEDEX: What was the driver for that?

Ruth Ballweg: Standardization and status. That, and the fact that it was hard to say to people that PAs are going to have this level of responsibility with only two years of training. Now, in reality, it’s not that simple. That would be the minimum they would have and most people had prior careers. But it was too confusing. That was too much for media to swallow, to give two messages instead of just one. NPs also went through a painful move to the master’s degree. And now they’ve moved to the doctoral degree, which is a whole other story.

The issue is: the more degrees you have, the less diversity you have. And that’s already true of the programs that are master’s degrees in the U.S. They’re almost all women. And it’s quite shocking to go to them and to see that 80% of the people sitting in the class are females. And a lot of them are young have no prior clinical experience which for years was the hallmark of our profession.

So, there were two pieces to the discussion. First of all, did we need the bachelor’s degree? And subsequently, did we need the master’s degree? But there were a number of new programs being created that some of us were concerned about as appropriate sites for PA programs.

MEDEX: Such as?

Ruth Ballweg: There was a concern about the right home for PA programs, with the right support, and the right value system. The drive to the masters program was partly about that. And the other big driver was that the nurses had moved toward masters, prepared what they called degrees. There was a controversy among nurse practitioner programs as well because they had certificate programs.

It was decided to go to the master’s in nursing, even though the nurses didn’t agree with this. In nursing, decisions are made by the Academic Deans of Schools of Nursing, and they don’t really care what anybody thinks. They are notorious for that. They’re all about promoting the professionalism.

So the whole NP thing was about NPs being more equal to doctors, being more empowered and having their own profession. It was about the profession of nursing. Fine, good on them, you know. But then the Nursing Deans really took this very hostile attitude towards PAs. They started attacking PAs. That was really uncalled for and how this all worked before.

It went something like, “Who the hell are you? You don’t even have a graduate degree and now you’re doing all this.” These arguments forced us into the master’s degrees. The other issue is that they’re not really legitimate master’s degrees. They didn’t change anything. It just added a little research project for most programs.

MEDEX: You mean like our Capstone project?

Ruth Ballweg: Well, we actually added a lot more things to the MEDEX master’s program so we could be happy about it. I mean we only got happy when we had the four different choices. It was material that was actually new content that would be valuable to people. Not everybody did that across the board. Some of the new programs that came from liberal arts colleges, they took the PA curriculum and added some ridiculous requirements. In some places you can write a literature review with three or four students together, and that counts as your Capstone project. I mean, I could do that on a Saturday afternoon.

For a long time the ARC-PA [Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant] wisely took no position on degrees at all—bachelor’s degrees, certificates, they were silent on all of it. Which I think was a good thing. But when this happened, eventually there was so much pressure that they finally decided, and they’ve phased in the master’s degree slowly. By 2021 all PA programs will have to admit master’s level classes.

And, again, if it was a real thing, I might feel differently about it. But it changes the diversity. I’m proud of what MEDEX has done, just to be clear. We really worked through it. When we finally decided to do it at a retreat, we had to pass around Kleenex boxes. I mean there was sobbing going on, from pretty much all of us. It was like, “Well, this is the end of it.” And then we kind of thought about it, and we thought, well, how can we make this fit within the context of MEDEX? And that’s why it has the pathways and it clearly has some values. And it has a significant work project to it.

So I believe it is a legitimate master’s degree. I don’t think that’s the norm when you go around the country and look. Right now, there are over 190 PA programs—and soon to be more. For years, there were 120. I’ve been to 80 of them.

MEDEX: One thing is very apparent. You meet people in the MEDEX program who might be the first person in their entire family to obtain a bachelor’s degree. For some, this has been their path to the middle class.

Ruth Ballweg: Well, I think people worry about the loss of that as we head nationally to the master’s program, but it’s less likely to happen in MEDEX than other places. I have this national view of the physician assistant profession. Right now I’m consulting with five different PA programs on a variety of different topics. And they’re all over the country, so that gives me the chance to see what’s going on. It’s my job to be the objective person giving them advice.

I’m mostly concerned about eliminating the diversity in the profession, that’s too bad. Programs are choosing younger people who are more likely to go into specialties, because it’s easier to think about one area of focus rather than primary care.

The Challenge of Preceptorships

MEDEX: Let’s talk a little about that. Here at MEDEX there’s an emphasis on a 4-month family medicine preceptorship. Any thoughts about that?

Ruth Ballweg: The only reason we went from six months to four months was because the ARC-PA had requirements for different types of practice—orthopedic, behavioral health, etc. A longer family medicine preceptorship created a valuable continuity experience. The students were in one place longer. There’s nothing replaces that kind of thing. It also changed who we recruit and what the value systems are.

But the reality is, aside from MEDEX, primary care is having a hard time everywhere. I gave a talk to the family medicine CME in September about hiring PAs and NPs. And they don’t do a very good job of it. It’s partly their culture. If they are going to hire somebody, they interview them. It might take four months to decide, because everybody, including the janitor, chimes in. I come from family medicine, so I like that. But it takes too long!

When it comes to specialties, they send their HR person and hire them after one phone call with the doc. All that, plus a hiring bonus in 36 hours. Well, family medicine can’t compete with that. Or if you’re going to get there first, you better decide to be competitive.

Students that really want a primary care job, can’t wait. They can’t wait for four months to start a job. Eventually, they or their spouse is going to say, “Get on it, buddy.”

So I think there’s some problems with the culture of primary care, specifically. They have a hard time. Residencies, family practices and even systems which are primary care leaders, are way too slow in hiring the people that they want. When addressing primary care doctors, I said, “If you find somebody, even if it’s their first month of training and you think they are a good fit, hire them.” Or at least have a call back. Don’t wait! Primary care practices think that PAs and NPs are a dime a dozen, and it’s not true. They all have multiple jobs offers. It’s not realistic to think that they can sit around and wait.

Looking Ahead At The Profession

MEDEX: I wonder if you could talk about what you see as the future of the profession. What are some of the challenges and what are some of the positive things that you envision down the line?

Ruth Ballweg: Well, concerning PAs in leadership roles, we’re behind in this on the west coast compared to other parts of the United States. PAs have always been reluctant to do that. Of course having advanced degrees makes leadership roles more open. But that wasn’t really the reason why people haven’t done it. I think PAs are PAs because they want to do clinical medicine. They don’t want to do research, they don’t want to be administrators.

We choose people that like to be with patients and that patients love. So why would you change that and become an administrator? The problem is our profession won’t move ahead. Nursing is just stellar about moving people into leadership roles who then make decisions and hire more nurses and nurse practitioners. But if we don’t have PAs who are around the table, we are losing out.

It doesn’t mean everybody should be a leader, but I actually think that every PA ought to do some kind of leadership, and it doesn’t have to be in healthcare. But it’s about visibility. They should be in some committee. They should be a Boy Scout leader. They could coach their kid’s soccer team. All those things teach you to be leaders, and they’re interchangeable skills. The same thing that makes you a good soccer coach ultimately might make you a good chief PA in a hospital.

That’s where I think we’re dropping the ball and I’m actually working on that.

MEDEX: Well, in fact, part of your recent gift to the University addresses that. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Ruth Ballweg: MEDEX has funds we can give students for various things. We don’t really have designated funds to send students to leadership kinds of training. These trainings are available, and there are people that would like to do that—especially those who would be the best at it because they are community leaders. But many can’t go. They don’t have a lot of extra money sitting around. And it’s true on all of our four sites. There are potential leaders, but they don’t have the resources.

Right now I’m working with a couple of our senior students that are submitting proposals at some of the PA conferences and they’re wondering how they can afford to be able to do this. And that’s why I’ve created this new fund that can go to support student activities. It’s carefully designed so that it has to have representatives. The choices will be made by leadership—the Chief PA at each of the four MEDEX sites—so it can’t just be all Seattle. By definition the funds have to be distributed among all the sites, which I think is important.

MEDEX: You contributed $25,000 of your own money to the fund.

Ruth Ballweg: That’s just the seed money that’s required to establish a fund like this. I’m hoping PAs—MEDEX graduates and others, including physicians—will make their own contributions to this important cause.

MEDEX: So you’re looking for other people to contribute to the fund as well. And when will the fund mature for its first gift?

Ruth Ballweg: I think maybe next September, 2017. But we have several student emergency funds as well. A number of MEDEX faculty have been contributing to these emergency funds over time, you know—Linda Vorvick and Gino Gianola. We hope other faculty, PAs and MEDEX graduates will contribute, too.

There’s also now a PA scholarship fund at Group Health that I’ve been involved in creating. It’s built with the idea to support Group Health people that want to go to PA school, and to have the PAs within Group Health help fund it out of donations from their salaries.

The summary is that physician assistants need the infrastructure that exists for doctors and medical students. There should be a PA sitting around every table that has to do with where our profession’s going—with licensure, with the insurance board, with whatever. If you ask me about my career today and what I’ve been doing, my view is, “Okay, is this a committee or a board that doesn’t have a PA on it? Well, let’s solve that.

MEDEX: Your career has been exemplary in that way.

Ruth Ballweg: Well, I just want to be the role model for people, and to open doors that remain open for “the next PA.” The world is run by people that show up, as you know. And we haven’t. Well, we’ve been busy getting our careers established. We’re not that old. But now we must. In the same way that originally PAs were all about access—which I think we still are, at least here on the west coast—we need to next be about being change agents.

I think that PAs can do that better than other people. We don’t have the constraints that doctors have about formality. We work the room a little differently. The most effective PA leaders I know in hospitals and whatever get things done by having relationships with people.

Life Today

MEDEX: Let’s talk about changes in your status. So, you’re not reporting to an office every day anymore. But you’re plenty busy from what I can see. What do you have going on?

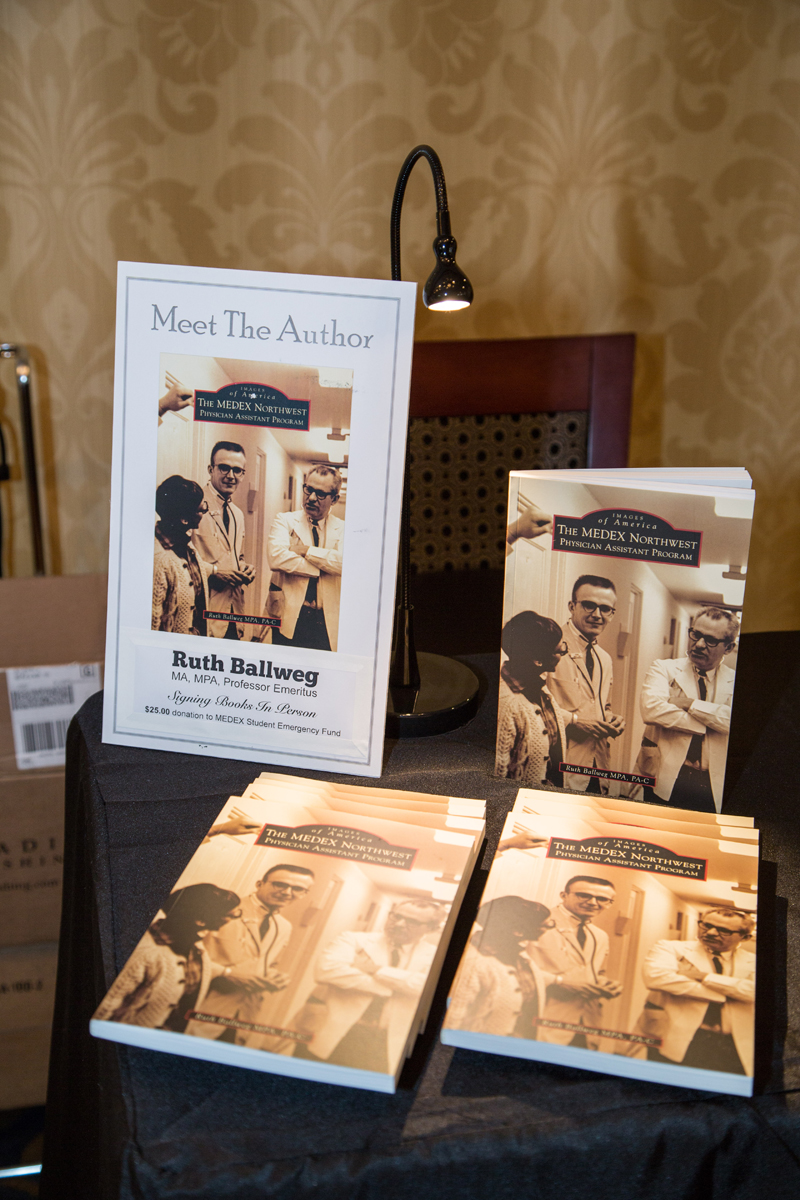

Ruth Ballweg: Well, I don’t think I’m working any fewer hours than I was before. And I don’t think I ever will unless I’m not well enough.

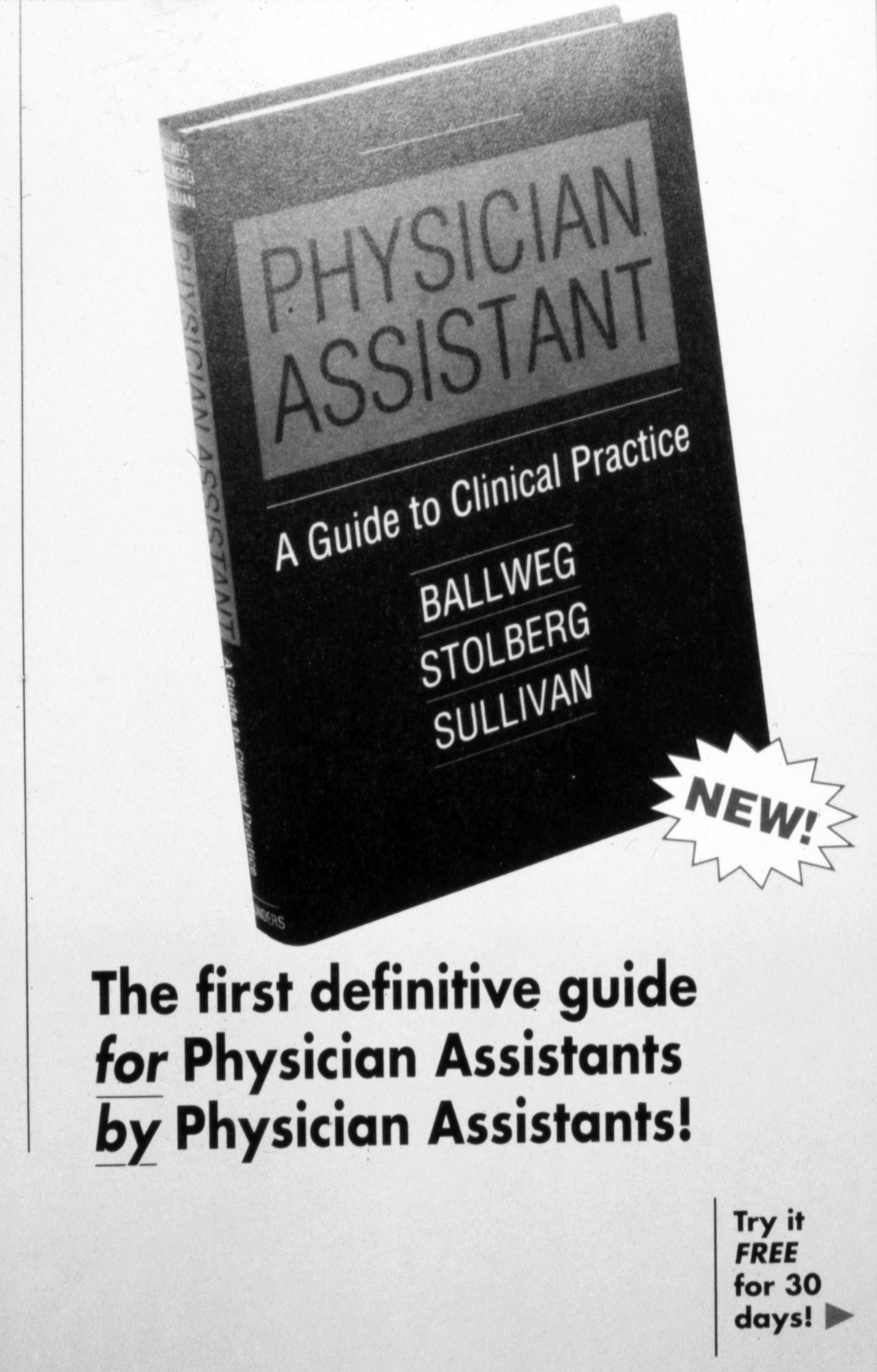

One of the things that I’m doing is writing. As you know, the MEDEX Pictorial History is out. But I’m doing some other writing. I’m also helping curate the 50th anniversary articles for PAEA and AAPA because of my role as one of the two historians for the PA History Society. I’m very involved in the PA History Society. It’s growing and thinking about its own infrastructure. It’s fun to do that with Reggie Carter, who was originally the Director at Duke— yet another person who went through all that hell back in 1985 about grant writing. And I’m still in the NCCPA [National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants] role as director of international affairs.

MEDEX: And are you still doing any international consulting on PA programs?

Ruth Ballweg: Indirectly. I’m going to London tomorrow. The NCCPA funds me to advocate for moving towards regulation and that sort of thing. But it’s also about building relationships with policy-makers, regulators, heads of medical associations and deans of medical schools. I’ve collected quite a network of people around the world that I know. What those people all want to do is they want to be connected up with somebody, just like the early days of PA. There are programs in other countries that are in the same stages of development and I can kind of hook them up.

So those are things I’m doing. I imagine that, with the acquisition of Group Health by Kaiser, which is going to take quite a while to straighten out, I expect I’ll end up volunteering or getting pulled into some of those governance discussions.

MEDEX: Tell us why you’re involved in that.

Ruth Ballweg: Well, I’m a former board member of Group Health, and for that reason they hope to use us as advisors and people to be in committees. Also, I was chair for two years during some of the early Affordable Care Act discussions. Anyway, I imagine that I’ll get involved with Group Health for short term kind of task forces and such, and that’ll be fun.

Also, I’m a mom and a grandma. I don’t imagine that I’m going to run out of things to do.

MEDEX: I don’t see that happening any time soon.

Ruth Ballweg: The other thing that I do, informally, is mentoring a lot of people. I’d would say I participate in 10-20 phone calls a week with people that are people I know, sometimes people I don’t know, particularly in the global environment, that just want somebody to talk to who’s been around the bush a few times and they just want to know, “Does this sounds like a reasonable idea?” Some of them are MEDEX graduates. But some of them aren’t. Some of them are people looking at jobs in New Zealand, some of them are people that want to be faculty overseas. As long as I have the time, I usually take their phone calls. They’re either people I know, or they get referred to me by a former program director who is a friend of mine. It’s a part of networking. I enjoy that.

MEDEX: Anything else you want to add at our conclusion?

Ruth Ballweg: There’s an overarching thing aside from how we survived and how we grew. I think that people that have been in my shoes over a period of time, we pretty much would all say the same thing: it’s all about the students. That’s what the rewards are, and making sure we choose people that value the unique opportunities to be found in the PA profession. Meaning, do they care about people? Are they willing to go that extra mile? Do they care about relationships?

Because our students are older, difficult things happen to them while they’re in school. Sometimes you get involved in the most wonderful and incredibly sad aspects of their lives. The bonds that are created through those experiences will never dissolve.

You know, Dick Smith talked about people giving him a bad time when he moved out of clinical practice. But he said it’s about multiplying your hands 10,000-fold. Well, being a PA faculty person and a director especially, you get the chance to do that, and nothing will ever take that energy away from you.

The sadness, the tears, the laughter—it’s all about the human condition. It’s worth every second. Sometimes the person that just drives you most crazy turns out to be the best clinician, or the most effective leader who pushes for change in just the right places.