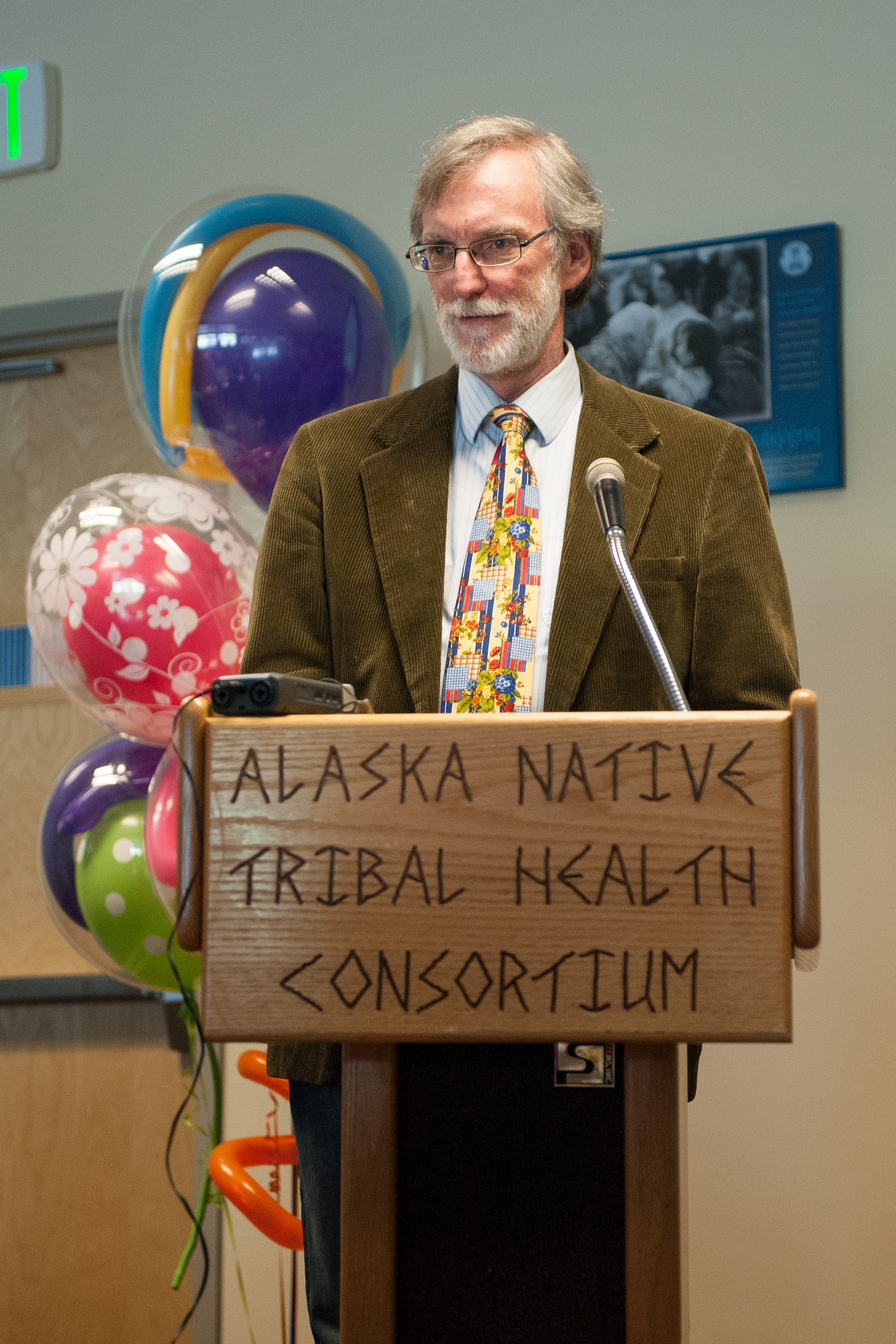

Louis Fiset, D.D.S.

After a 10-year hiatus from dentistry, Dr. Louis Fiset broke ranks with his fellow dentists to focus on growing the dental therapist profession in Native Alaskan communities. The DENTEX program has been a collaboration between the UW MEDEX program and the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC). Now, 10 years on, Louis reflects on his contributions to this movement, and the value of fighting to bring mid-level dental practitioners to underserved communities in the lower 48 states.

MEDEX: How long have you been working on the DENTEX program?

Louis: I’ve been working on the program since I guess 2006, but my involvement actually preceded my coming to MEDEX. In September of 2005, I was 10 years into my retirement from dentistry altogether. I was living the life of a writer, contributing to the historical literature, when I got a phone call from a former colleague in the UW dental school, with whom I had done post-doctoral work in the early ’80s.

Dr. Peter Milgrom and a psychologist colleague had started a special clinic in the dental school to treat patients who were phobic. When I came to do my post doc, part of my work was to learn how to do research, and part of our research involved working with and studying the phobic population.

So, I worked with Dr. Milgrom for over a decade, but then decided it was time to do something different. So I went off on another 10-year stint working as a writer, focusing on research involving the Japanese-American experience during World War II. Ironically, this is how I happened to come to MEDEX.

When Peter first called me, he was aware I had some cultural sensitivity. He was also aware that I had been away from dentistry for a decade, was not involved in dental politics, that I had some research skills and was an acute observer.

And he asked me, “Would you like to go up to the Arctic?” And I said, “I’d be happy to. Was there any particular reason?” The reason was that the first four dental health aide therapists had returned from two years of training in New Zealand and were just finishing their preceptorships. They were about to go out into off-road Alaskan Native communities to practice dentistry. And the program director wanted someone from the outside to evaluate their clinical competency.

MEDEX: What was Dr. Milgrom’s involvement with that?

Louis: Dr. Milgrom and Ruth Ballweg had been talking since 2004 with Dr. Ron Nagel, who was working with the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) to bring mid-level trainees into Alaska to attack the problem of an epidemic of dental tooth decay.

Dr. Milgrom was interested in placing the program in the dental school, and he and his colleague Dr. Marco Alberts and MEDEX Director Ruth Ballweg entered into some discussions on how that might occur. And they engaged the dean of the dental school who was originally quite supportive of housing the training program there.

But the dean’s enthusiasm deteriorated when leaders within the Washington State Dental Association got wind of this and successfully ended the possibility that the program could be housed in the dental school. This lead to the program becoming part of MEDEX.

Turns out it was a natural fit for MEDEX because the model that they wanted to use for a dental therapist was similar to the PA model. The dental health aide therapists or DHATs would be trained to work under a limited scope of practice while under the supervision of a dentist.

MEDEX, Dr. Milgrom and Dr. Nagel entered these negotiations and finally an agreement was reached with ANTHC whereby the first year of training would be under the direction of MEDEX Northwest, at the end of which we would issue a certificate to the students. That was the didactic part. And then the clinical training would be done under the auspices of ANTHC, and a second certificate would be given at the end of training.

So an agreement was signed, and they were looking for a curriculum coordinator. I had expressed interest to be involved with the program. When I did go up to the Arctic and saw what these dental therapists had been trained to do and what they were doing, I thought that was very exciting. I wanted to be a part of it.

MEDEX came and asked me to join the team. Dr. Alberts came over from the dental school. We shared an office and began to build a curriculum for the program. In the meantime, we were interviewing applicants. We went up to Anchorage and had a day-long admissions conference. I think we must’ve interviewed 15, 16 candidates and finally decided on seven.

And off to the races we went! We were building curriculum and were only about six weeks ahead of the students. And the students in their first year were warehoused— literally warehoused— in downtown Anchorage in an empty space. It wasn’t until the second year that we actually moved into a legitimate space.

But the fireworks started soon after my trip to the Arctic. The American Dental Association and the Alaska Dental Society brought suit against those practicing dental therapists with the idea of shutting down the program altogether. They said that we were violating Alaska state law and trying to avoid state dental licensure laws. This lawsuit went on for a while until the Alaska State Attorney General said, “Look, this is a sovereignty issue and you have no standing.”

MEDEX: Were the patients of these dental therapists meant to be Native Alaskans in tribal areas as well?

Louis: That’s correct. It was always understood that the students who we recruited from Alaska native villages would be trained by us, and then they would return to their villages to live and work. They would be under contract with the tribal health organizations that had sponsored them in the first place. And the dental therapists were allowed to treat only Alaskan natives as well as public health service employees. And that’s how it continues to be even today.

MEDEX: Which was really a winning argument against the lawsuit as far as the Attorney General.

Louis: That’s right, because this was a sovereignty issue. There was no attempt to be competitive with dentists in downtown Anchorage. The federally certified dental therapist could only practice in underserved Alaska Native villages.

MEDEX: Now, tell us why that’s so important. You mentioned an epidemic of sorts. But tell us what goes on. For those of us who are not familiar with Alaskan native villages, tell us what happens there.

Louis: About 80,000 Alaskan natives live in remote rural off-road Alaska where the only way to get into urban areas is either to fly in, to boat in or, during the winter, travel by snow machine or dog sled. These are very, very remote areas of Alaska.

Historically, these villages have been served by itinerant dentists who would fly into the village once a year, maybe once every other year, weather permitting. Basically they would handle emergency needs. They would extract a lot of teeth, try to eliminate infection, perform fillings on teeth that weren’t ready for extraction. And then they would leave.

The problem with that model is that there was never any opportunity to teach the patient or the community that there might be another way to approach dentistry. That, in fact, it’s possible to prevent these problems from occurring in the first place.

So the itinerant dentists would come back the next year and see the same patients and extract more teeth and do more fillings. Eventually many patients would end up without any teeth, and therefore condemned to wearing dentures.

It turns out that Alaska natives and Native American children have about five times the rate of tooth decay that their cohorts do in non-Indian country. A quarter of the kids miss school sometime during the year because of dental pain, and almost 90% of teenagers in the Alaska native and Native American populations have active forms of tooth decay. So it really has been an epidemic. It’s the itinerant dentists themselves who have told us we’ll never be able to solve the epidemic problem by using this model.

This is what inspired ANTHC to look into the possibility of training and hiring mid-level providers—non-dentists who could be specially trained in preventive services and basic restorative care. These individuals could be recruited from the villages, would possess the cultural competency and the desire to return to their villages, and would be able to take care of the needs of the villagers on an everyday basis.

In dental language this is called continuity of care. That is, you take care of the basic problems to get the patient out of pain, and then begin the pathway toward preventing a recurrence of decay. That was the model.

We decided that it was necessary only for those that we recruit to have a high school or a GED education. Over the past 10 years we have found that, in fact, we can train high school graduates to perform these procedures, and be able to provide enough education in diagnosis and treatment planning, to be able to work under the supervision of a dentist.

And by supervision, I mean the dentist might be at a regional center 150 air miles away. But because they have telemedicine, telephone and the like, the dental therapists can be under supervision at all times, depending on the needs of the patient and the training of the dental therapist.

MEDEX: Obviously you had a supervisory role in managing the curriculum for the didactic year, is that correct?

Louis: I had several roles. In the early days, I was responsible for recruiting faculty, which I did from the University of Washington, University of Florida, Minnesota, Baylor University—from many different places from throughout the country. And then my colleagues in Alaska recruited faculty from the Public Health Service and the Indian Health Service.

Once they were on board I had to help provide the teaching materials because our curriculum was very different than what is taught in many dental schools.

Ours is an evidence based curriculum. We had to be aggressive in what we taught our students because we were dealing with such underserved populations, and the extent of tooth decay was so great.

For example, one of the strategies that we used was to paint surgical scrub (Betadine) onto patients’ teeth, on top of which we applied fluoride varnish. There’s a lot of evidence for the efficacy of those treatments, but this strategy is not taught in most dental schools or in hygiene schools.

We actually had a couple of dental hygienists go through the program, and they asked us ahead of time, “Well, I’ve got all this training as a dental hygienist, are there some classes I can skip?” And the answer was no. First of all, it was important that the dental hygienists unlearn some of the strategies that they learned in hygiene school.

The strategies that we were teaching the students, they had never heard of in many cases. So anybody who comes into the program with a background in Oral Health Sciences has to go through the entire program because our teaching methods are so innovative.

MEDEX: I didn’t know about that. That’s pretty impressive.

Louis: One of the other roles I played was to sit on the student progress committee. I would visit the students on at least three occasions throughout the clinical year. I would travel to the Bethel training site. Bethel is 400 air miles due west of Anchorage, out on the tundra. I would observe the clinical year students in clinic, have private conferences with them, and then write a report for the program director based on my findings.

Often I served a role as student advocate. Basically I was from the outside, and I would be able to see some of the difficulties the students were having as much in their personal life as with their professional life. I was able to build enough rapport to make a difference in the lives of some of the students who were going through great stress being involved in this program.

The students all came from villages of anywhere from 200 to 500 people—very small places. In Anchorage, they’d come into big city life, which was a difficult adjustment for some. Even Bethel, with its population of 6,000 and tundra climate was very different than what some of the students were used to.

Students invariably had a lot of homesickness. The nuclear family and even the extended family are very important to Alaska Natives. So there were a lot of the personal problems associated with that. There were pregnancies during the year, there was domestic violence, there were alcohol and drug issues, and there were even suicides in the families back home.

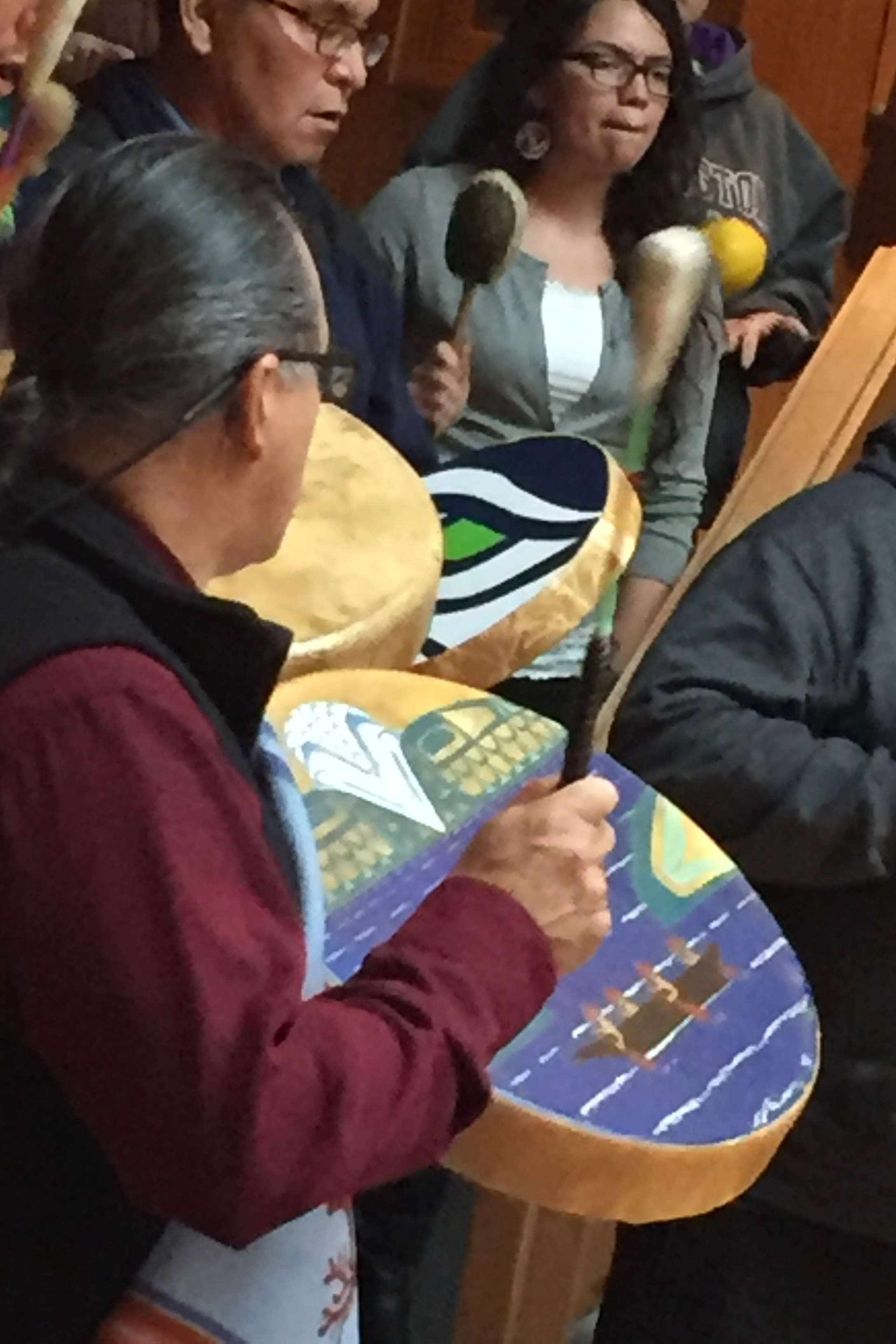

I have to say that I have profound respect for the students that I met, just because of what they had to go through in their lives just to get to the program. Let alone going through the two years of training, being away from their families and their subsistence living. What they endured is something that I found very humbling.

I found my greatest joy during the year was at graduation, when the graduates would step to the podium and thank their families for sticking by them during these tough times. The people I saw at the podium with certificates in hand, I could remember back to the beginning of the school year, and see how they had matured as people during that year. I could see what a difference the program made in their lives. I could think ahead a few years to when they were out on the village, practicing and serving as role models to other people. Perhaps younger people in their community who might look at them and say, “Gee, maybe I can do that, too. And maybe I should graduate high school. Maybe I should stick it out and graduate because maybe there is some hope for me.”

And I tell you, I then leave the graduation ceremony ready for the next year’s students. That’s pretty much the role that I played throughout the school year for the students in the program.

MEDEX: At the same time on a parallel level, there were efforts to bring the dental health aide therapists to the lower 48, and there was success in some other states. You were part of an ongoing lobbying effort in Washington State. Tell us about that.

Louis: The Alaska dental therapist program was the first of its kind in the United States. That shouldn’t make us proud, however, because we were the 52nd country in the world to embrace the concept of dental therapists. New Zealand has been training dental therapists since 1916. And for 10 years the Alaska program has operated in a fishbowl.

Most of the people looking at us have been detractors. They wanted us to fail, and we refused to cooperate. There are a minority of observers who are saying, “Gee this might work in our state and in our communities. Let’s learn more about it.” And so the Kellogg Foundation, who has been an underwriter of the program since the beginning, has sponsored multiple visiting opportunities throughout each year whereby health professionals can travel to Alaska and see firsthand what is going on in the program.

And as a result, the concept of dental therapy in the United States has spread to a number of states. Minnesota has been training dental therapists for a number of years, and their graduates go into underserved areas, providing care in those areas. Maine’s legislature recently passed legislation that will enable the training and the licensing of dental therapists in their state.

In the Pacific Northwest, it’s taken on a little bit different direction. It turns out the tribes in Washington and Oregon are taking the lead. The Swinomish tribe, located north of Seattle near La Conner, has recently hired a dental therapist from the first Alaska-trained graduating class. He came on staff at the beginning of January 2016, and is now providing care alongside the dentist.

Oregon passed legislation that would allow for demonstration projects for mid-level providers in oral health care. And the Portland Northwest Area Indian Health Board submitted a proposal to train and hire dental therapists to work on tribal reservations in Oregon. Recently this application was approved.

Right now, there is a Native American student training in Alaska from the Coos Bay tribal reservation. And the Swinomish community has also sent a student up for training. They’re both in the first year of training so in another year they will be returning to their tribal communities to provide care on the reservation.

Now, the Swinomish have reached out and asked my colleague, Dr. Milgrom, to design a program that will enable them to assess the contribution of the dental therapist and increase access to care for elders on the reservation. And Dr. Milgrom has asked me to help him in this endeavor.

So that is in the offing. With the tribes taking the lead in Washington and Oregon, and their interest in assessing the effectiveness of the mid-levels coming onto the reservation, I think it’s just a matter of time before dental therapists will be allowed to practice in Washington State under state licensure.

These are exciting times. I had little hope that, 10 years after the fact, we would be this far along given the opposition from organized dentistry both at the state and the national level. I think opposition is beginning to decline slowly. The arguments used by organized dentistry have focused traditionally on safety issues. And what we have found over the last 10 years is that there have been no complaints or malpractice suits brought against dental therapists.

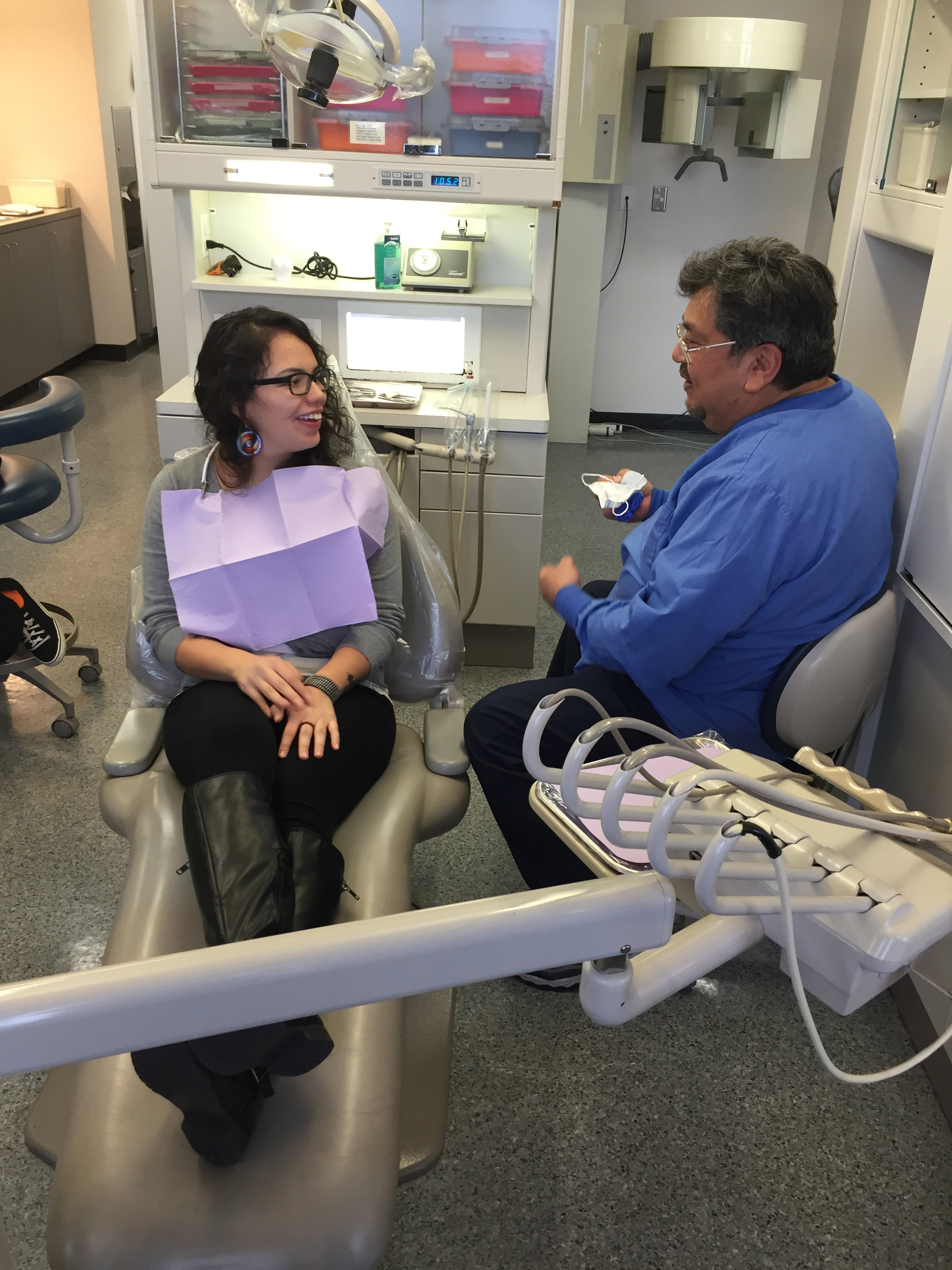

There was a two and a half year scientific study done of the first dental therapists who returned from New Zealand. The conclusions were that these dental therapists are providing safe, competent, and appropriate dental care to the villagers and they are being well received by their communities. In addition, when there was an opportunity to compare the work provided by the dental therapist and the work provided by the itinerant dentist, the researchers were unable to find any differences between the quality of the two.

The opposition is beginning to weaken in terms of the safety issue. Now the opposition seems to be more toward, “Well, we already have sufficient numbers of health care providers to be able to take care of the needs. We’ve got General Practice residents who are just itching to get out into the community and help under-served areas. We have programs at the University of Washington to introduce students into rural areas many of whom will go on to stay, to live and work in those areas.” So they think there are no manpower needs, that the dental therapists are unnecessary. Our view is we need all the help we can get.

So often, access issues are so acute that sometimes the only recourse for patients is to go to the emergency room. Doctors and nurses in emergency rooms are usually not well trained in treating routine dental emergencies. And what they generally do is to write prescriptions for pain and antibiotics, which is just simply a Band-Aid and, at the same time, expensive.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful, for example, if a dental therapist could be on staff in a hospital in an emergency room? Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have a dental therapist in a medical home, where there are pediatric services? And that’s where an infant is first seen is in a pediatric office at six months when the teeth first start coming in.

Why couldn’t a dental therapist be there and begin to provide the preventive services that will prevent dental problems from the beginning. Sometimes if we wait until the patient is two years old and has his full set of primary teeth, that’s too late. Tooth decay is already well underway.

If there can be interaction between the medical and dental profession, why can’t physician assistants and dental therapists work together? Why can’t they teach each other some of these preventive strategies? Imagine a medical home where you have both mid-level providers onboard?

I see this as happening down the road. I see dental therapists working under indirect supervision with their dentist whereby they can go out into a nearby community that’s underserved. And work in a clinic there providing care, so that the people in the community won’t have to travel long distances to see the dentist.

It’s not the first appointment that’s important; it’s the second appointment. The first appointment is where you get your tooth taken care of so it stops hurting, or where your child’s tooth stops hurting. And I’d take my kid across the state, if it were that. But would I take that same child to the dentist for a preventive visit?

Well, if I’m working at a low paying hourly job, and if my transportation is unreliable, no I probably am not going to do that. But if I have somebody come into my community where I can walk to the clinic, maybe I would do that

And maybe if the dental therapist comes to my child’s school, and I know that a dental therapist is going to give my child preventive services, yeah, I’ll sign that consent form. You bet. And that’s the concept of dental therapy. We take the dental therapist to the community rather than waiting for the patient to come to the office. With this model the access issue isn’t so problematic.

MEDEX: What a revolutionary idea.

Louis: What a revolutionary idea? Yeah, one that’s been going on since 1916!

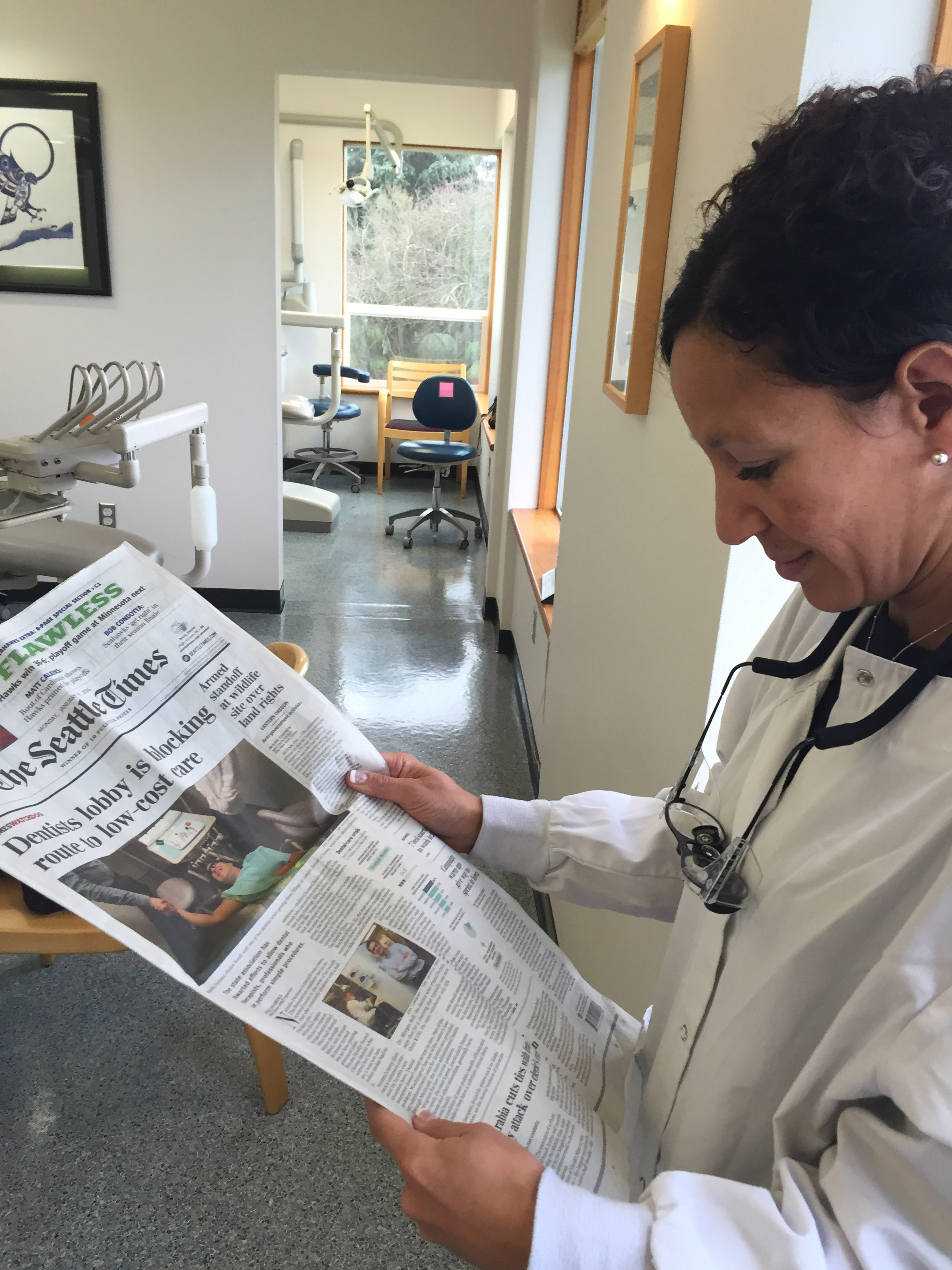

MEDEX: Recently there was a whole lot of noise in the media about this very issue. A Seattle Times reporter had covered this story about opposition within the dental profession to the idea of dental health aide therapists. You actually chimed in on that publicly. Can you talk a little bit about this recent hubbub, and how it’s brought this issue back into the forefront?

Louis: The hubbub started up again when the Swinomish tribal community announced it was going to be hiring a dental health aide therapist on staff. And this article that had been written several months previously was finally published in The Seattle Times at about the time the legislative session in Olympia began. And the article talked about the fact that the dental therapist was on board. And why this dental therapist was on board? Because of the unmet need.

The tribes had been trying to get legislation in Olympia passed for several years. They finally had said enough and decided to take the lead on their own. This brought a backlash from organized dentistry. There’s been a mail campaign out asking all dentists to write to their representatives in the legislature in opposition to ongoing bills. And so the issue is very much alive again.

There was some fear that once again organized dentistry would bring suit against the Swinomish for hiring a dental therapist. Earlier they had said we draw our lines in the sand of the 49th parallel. And so the tribe has built a war chest to oppose it. But what’s interesting is there doesn’t seem to be active resistance like there was before. The tone isn’t vitriolic; the tone is “Well, we already have the manpower that make dental therapists unneeded.”

MEDEX: Why the softening do you think?

Louis: I think a couple of reasons. One is I think that they’re getting used to the idea. I think that they are seeing that this is a popular idea among the people. I think they realized that the safety issue is no longer viable. There is so much evidence to say that safe care is being provided by dental therapists. And I think there is a certain fatalism beginning in the minds of organized dentistry that they ultimately can’t stop it.

MEDEX: Do you think that fatalism could turn to embrace, much like with the early physician assistance profession? The medical profession really began to see PAs as a force, a tool of good within their industry.

Louis: That’s too altruistic. During times when I was having down days in the early days, my supervisor Ruth Ballweg would come to me and say, “You know Louie, we had the same arguments made against us by the medical profession when the PAs were first getting started. And what turned the corner was when physicians finally understood that the PAs could make them money, and that they could go home at the earlier at the end of the day.” It wasn’t altruism; it was a hungry stomach issue.

Dentists haven’t gotten that message yet. They will because there is evidence being compiled now that shows that dental therapists are helping increase productivity in practices in Alaska, and in Minnesota, so that’s coming. Once dentists get the idea that a dental therapist can actually make money for a practice, you’ll see dental therapists hired to manage basic fillings and prevention services. Then the dentist won’t have to do those things.

There have been estimates that a dentist spends about 50% of his or her time performing procedures that could be delegated. Delegation of those procedures would give the dentist more time to perform the big-ticket procedures—the implants, the root canals, the crowns, the bridges, the complex dentures. Perhaps, even working at the top of his license where he’s actually providing some medical care such as oral pathology. Focusing on the more complex procedures might lead to a more satisfying clinical practice. So stay tuned. In time the dental profession will get that message.

MEDEX: Now as for you, there is a change that you’re experiencing. Your association with MEDEX will end, and you will once again find your association with the UW Dental School as you work on these Washington State tribal issues. Is it appropriate to say this a research project right now with the Dental School concerning the Swinomish and the tribal elders?

Louis: Yeah, it hasn’t come to fruition yet, and we’re still in the talking stage with tribal leaders and with the grantors. But yes, that’s where I hope my work will take me in the future. If Washington State Legislature passes legislation that would enable training and licensure of dental therapists in the state, Seattle Community College has already expressed an interest in providing that training. Their allied health training program in place would be a good fit for a dental therapist training program.

MEDEX: So when does the Washington State legislature convene on this issue?

Louis: Once again, neither of the dental therapist bills got out of committee, so the issue is dead for one more year.

MEDEX: So in the meantime, it’s really the tribal communities that are taking the lead.

Louis: Yes. And so right now the tribes in Washington and Oregon are where the action is.

MEDEX: So we’re sitting in an office right now where your DENTEX files are all being boxed up and readied for storage. When will you begin working part-time with the dental school on this project, and where will you be located? How is this all going to play out in terms of your time?

Louis: I’ll spend an average of a day a week on dental research, dental projects. And the rest of my time I’m returning to my life as a writer. I have several book projects that I’m working on now, and I figure that I’ll be busy with those for another five years or so. And I’m keeping my options open with working in the dental arena. I’m enjoying working once again with my former mentor, Dr. Milgrom. Peter and Ruth Ballweg are two visionaries who also get things done. And where I might be in my involvement with Dr. Milgrom a year from now, two years from now is anybody’s guess. Who knows, maybe Ruth will be right there with me. And boy, I’m open to it.

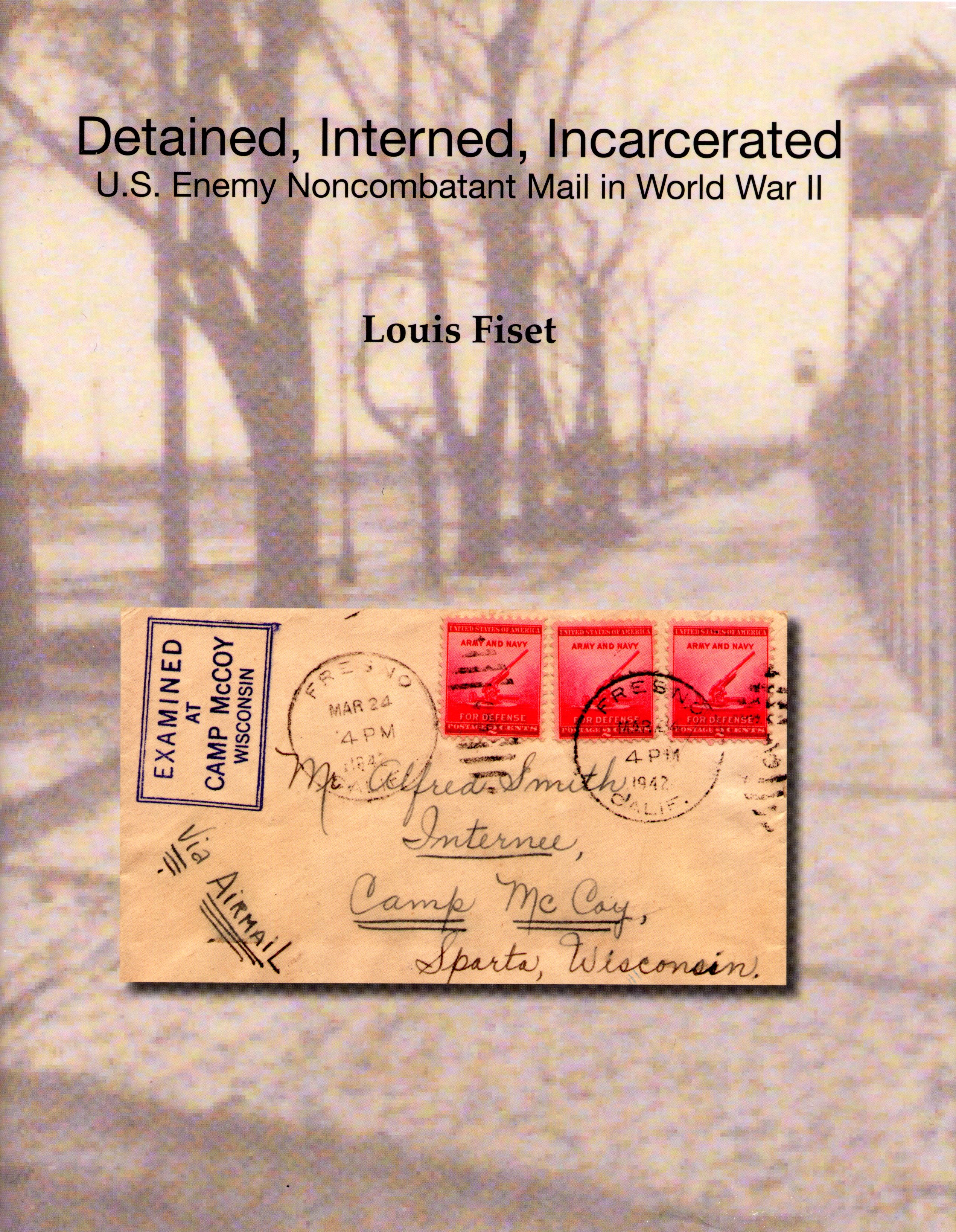

MEDEX: Well, we’re all watching. One thing that most people don’t know about you is that you’re well-known in another arena too, in the community of philatelists. Also, you’ve published your historical research and documentation around Japanese internment camps. Could you talk a little bit about that, just to inform people who don’t know about that part of your life?

Louis: Sure. Well, there’s actually an intersection between my philatelic life and my interest in the history of Japanese Americans. Originally, I got interested in the World War II experience of Japanese Americans when I came across a correspondence from a first generation Japanese scholar who was interned in a camp in Montana, writing to his wife who was incarcerated in a camp in Idaho. And of course, during the World War II, the only way to communicate was by mail. And it turned out this man was highly articulate in both Japanese and English. His letters were opened and read by government censors, and they got me interested in postal censorship.

There was this intersection between my interest in the impact of war on the transmission of the mail, and this man who was sitting in an American-style concentration camp simply because he was Japanese. I left dentistry thinking I would never return. And for 10 years I wrote peer-reviewed books and essays for the historical literature, talking about the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

And that experience also carries over into my philatelic interests where during that decade I was writing articles and books and exhibiting postal documents relating to that incarceration experience. It was really an intersection of two loves that continue to keep me engaged and passionate in thinking and uncovering new facts and documentation.

MEDEX: Well, it requires an inquiring mind, for sure. Anything else that you would like to add or say at this time? Anything we forgot to cover.

Louis: I don’t think so, except that I will certainly miss the people in MEDEX who themselves have inquiring minds, and furthered my education in how to provide care for underserved communities.