Congratulations on choosing family medicine! We are thrilled to welcome you to our specialty and want to help you match to the residency program that fits your personality and career goals. We hope the following pages answer some of your questions. For one-on-one counseling, please fill out our Advising Intake form to be matched with a faculty advisor.

Helpful references to help you apply in Family Medicine

AAFP Strolling Through the Match (updated each year)

NRMP How the match works (5 min video)

WWAMI Network Family Medicine Program List (by State)

WWAMI Program Interview calendar

AAFP Residency Program Search Engine

The ERAS application

Start by considering these questions to determine what you want out of a residency program.

What does your ideal future career look like? What clinical skills will you need to reach this goal? Do you want more experience working with particular populations? Do you prefer working in larger or smaller settings?

Consider your personal circumstances. Do you prefer living in a particular state or region? Where does your social support system live? Do you have a partner? Children? What community resources will you and they need? Will you be couples matching?

Go beyond the databases. Schedule Sub-I’s at programs you are highly interested in. If you do not have the time for a Sub-I, consider asking the program if you could shadow residents and faculty for a day. Talk with your faculty adviser/mentor about what programs are a best fit for you. Talk with the residency program coordinator or your mentor to find faculty and residents to talk with about the programs you are interested in. Attend the National Conference of Students and Residents and meet program faculty and residents from across the nation.

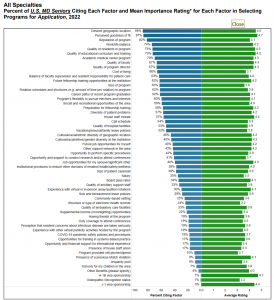

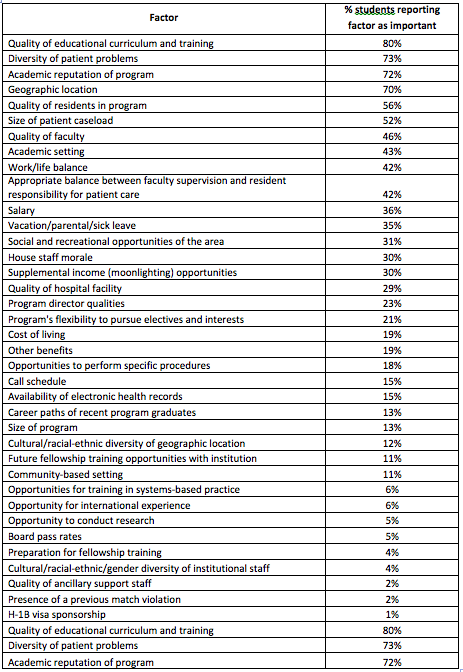

What do others find important? The following is a list of factors that US seniors identified as important when they were deciding on which residency programs to apply and interview. The table is listed in the order of percent of students reporting this factor as important. There are also some factors that were not on the survey that you may find significant, and there may be some factors not listed here that are critical to your own personal search. Use this table as a starting point to figure out what you want out of a residency program and how important each factor is to you.

Reference

NRMP. (2023). Results of the 2022 NRMP Applicant Survey by Preferred Specialty and Applicant Type. 8.

Students frequently ask about how to assess residency programs, including how to figure out how competitive a program is. Unlike some other specialties, there is no “Top Ten Family Medicine Residency Programs” list that tells you the best and most competitive residencies. Instead, each program has different strengths that will be a good fit for different students with different career goals. Figuring out what is important to you during residency will help determine which programs are a good fit to meet your needs and training desires.

Determining the “competitiveness” of a program can mean two related, but different, things. A program’s competitiveness can be a marker of its prestige OR it can indicate how difficult it is to match to the program because they have a strong applicant pool. Clearly these two are related, as more prestigious programs will have more applicants and thus may be more difficult to match into. However, many popular or prestigious programs may be a poor fit for many applicants because they do not meet the applicants’ individual training needs and desires. Try to keep these concepts separate when you are assessing programs – it’s fine to determine the prestige of a program and to use that when deciding where to interview and rank, but make sure you are also determining how hard it is to match to a program so you can make informed choices about your chances of getting to train there. And above all, don’t forget about fit. All the prestige in the world won’t do you a bit of good if the program does not offer the training you want.

- FREIDA (good for general information about residencies)

- AAFP (has more detailed information about FM programs)

- WWAMI Programs (information specific to WWAMI network residency programs)

- Residency Footprint Tracker (for students interested in rural or underserved careers – tells you the percent of grads from the residency that go on to practice in those areas)

- Prior year match rates (one way of assessing a program’s competitiveness is to look at prior match rates)

- Board Pass Rates. For your “safety residencies,” you may want to consider looking at the individual board pass rates.

Once you have identified programs you are interested in make sure to visit their website for detailed information. The websites usually have a list of current residents and faculty. Review the current residents for two reasons. First, see if they are people you can see yourself working with. Second, see if they seem like they were a more or less competitive applicant than you are to get a sense of the competitiveness of the program. You can also contact prior UW grads that are residents or faculty at an individual program to get more information about the program.

Students often wonder how many residency programs they should apply to. The short answer is that there is no magic number. A longer answer is more than one and probably less than twenty. However, it depends on many factors and you will need to take both your own competitiveness AND the competiveness of the programs you are applying to into account. Additionally, you may have extenuating personal circumstances (such as a partner in school in a particular city who can’t leave) that may make you feel you need to limit your search to that geographical area.

There are two ways of thinking about programs that will help you determine how many you should apply to. The first is to work backwards from how many programs you want to include on your rank list. The second is to categorize the programs based on how easy you think it will be for you to match into.

Reviewing data for US seniors from the 2011 match can help you know how many programs you should rank. In 2011, essentially all family medicine applicants that listed more than 11 programs matched. Students ranking only one program did not match 20% of the time and 16% of the time for those who ranked only two. The percentage of unmatched students drops for students ranking 3 or more programs. Although overall only 3% of US seniors did not match, those that matched ranked an average of 8 programs compared to the 4.7 programs for those that did not match. The take-home points from all this is that the longer the list the less likely you are to go unmatched. For the average student, ranking 10-12 programs will likely ensure a match. Work backwards from this number to account for attrition of programs during the application and interview process. Most students have 1-2 programs they do NOT want to attend after the interview and some students will probably not get offered interviews at every program they apply to. Furthermore, some students will get interviews but may decide not to attend them from a variety of reasons. Therefore, an average student would need to apply to about 15 programs to account for not getting interviewed at 1-2 programs and not liking 1-2 programs after interviews to be able to have a rank list that is 10-12 long. For this average student the application process may look like this:

- Applies to 15 programs

- Offered interviews at 14 programs

- Interviews at 13 programs

- Ranks 11 programs

Using three broad categories (stretch, likely, and slam-dunk) of programs can also help you build a list. Stretch programs are those that are more competitive programs than you are an applicant. It may be a stretch for you to match to them but could happen. Likely programs are those that their competitiveness and your competitiveness match up and you feel a match will likely occur. Slam-dunk programs should be seen as a safety harness so you don’t go unmatched. These are programs for which you are a very competitive applicant and you should have no difficulty matching. The concept of these categories does not obviate the need for good fit. You should not rank a stretch program just because it is more competitive if it is not a good fit for your training needs. Likewise, slam-dunk programs should also be those that fit your needs.

Stretch: The program is more competitive than you.

Likely: You and the program are about equal.

Slam Dunk: You are more competitive than the residency

How many programs from each category? Again it depends on your competiveness. An average student may have 2-3 stretch programs, 3-4 likely programs, and 2-3 slam-dunk programs. Students that have faced difficulty in school and are less competitive may need a longer rank list with more likely and slam-dunk programs. Highly competitive students may be able to get away with less than the average student, however it is important to remember that the fewer number of programs ranked the more likely you are to go unmatched – this is true for all students.

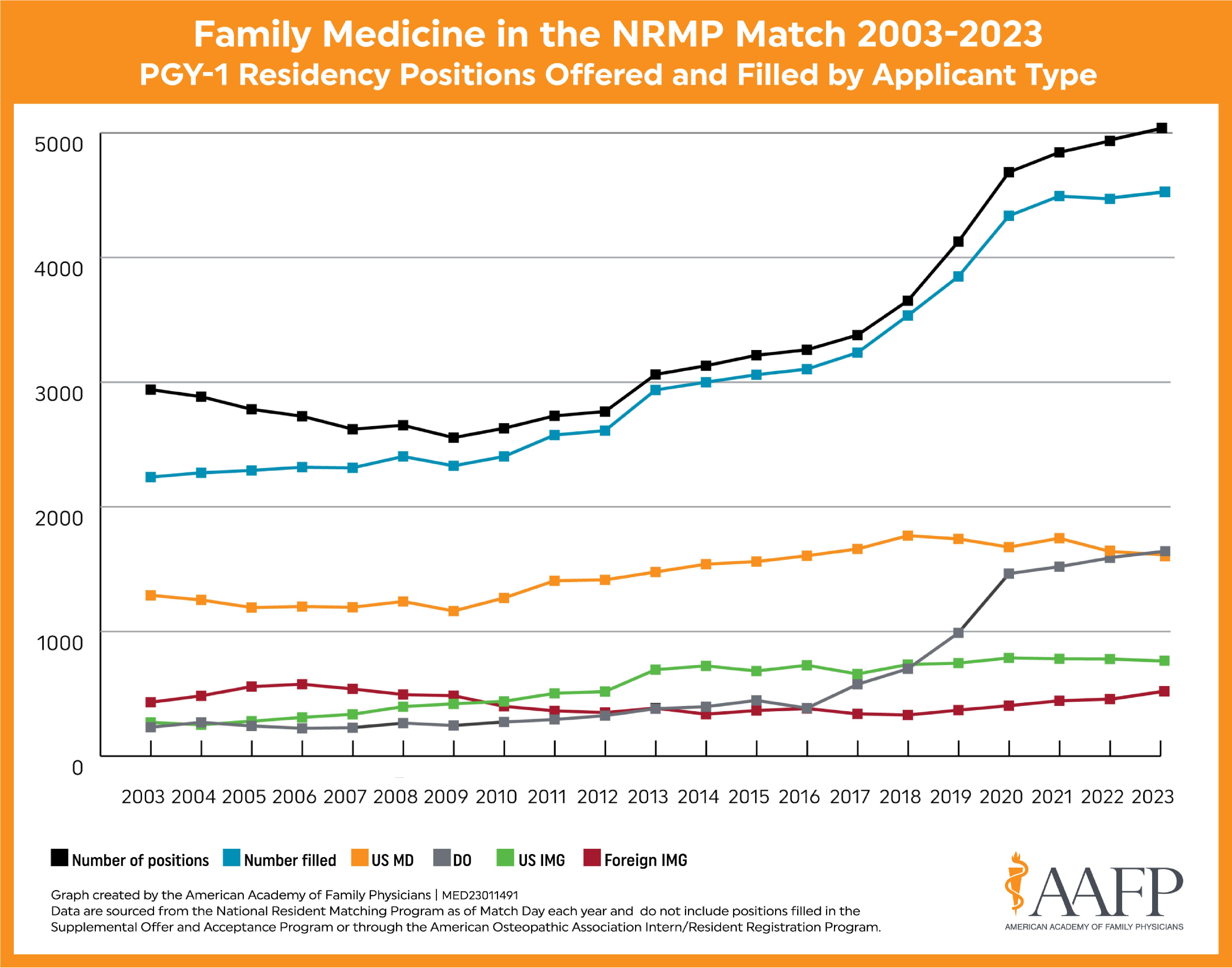

In prior years, going unmatched was less concerning because the number of unfilled positions was gigantic compared to the number of unmatched US seniors. In 2007, 13 US seniors were unmatched and could scramble into 304 open slots; in 2009 23 unmatched US seniors could scramble into 224 unfilled slots. In 2011, 29 US seniors were unmatched but only 153 slots were open. If you go unmatched and need to scramble you will likely face a smaller pool of choices then in years past. A further complicating factor for this year’s match is that the traditional scramble was replaced with a more organized application and matching process. Since this if the first year this more controlled process will be used, no one knows exactly what it will be like for students that go unmatched. Not being able to scramble into a program can be very dangerous. For all students that fail to make an initial match or scramble and then attempt matches in subsequent years, the match rate is has hovered around 45% across all specialties since 2007. This means that less than half of US grads will go on to make a match in later years if they fail to do so when the year they graduate.

So what do you do if you have circumstances that make you want to limit your match to a single geographically area or to a few programs? If family is involved talk to them honestly about what you think the chances are to match in your coveted area/programs. Discuss long-term ramifications if you don’t match (scramble to a place you weren’t expecting or go unmatched which probably makes you less competitive the second time around.) Keep in mind that residency in only 3 years long and that you are choosing a specialty that will let your work anywhere when you are done.

References

i) National Resident Matching Program and Association of American Medical Colleges. (2011). Family Medicine. Charting Outcomes in the Match: Characteristics of Applicants Who Matched to their Preferred Specialty in the 2011 Main Residency Match, Fourth Edition. 74-86.

ii) National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data. (2011). 2011 Main Residency Match. National

Resident Matching Program.

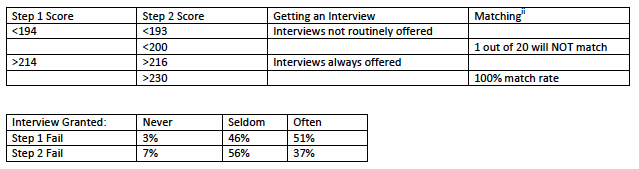

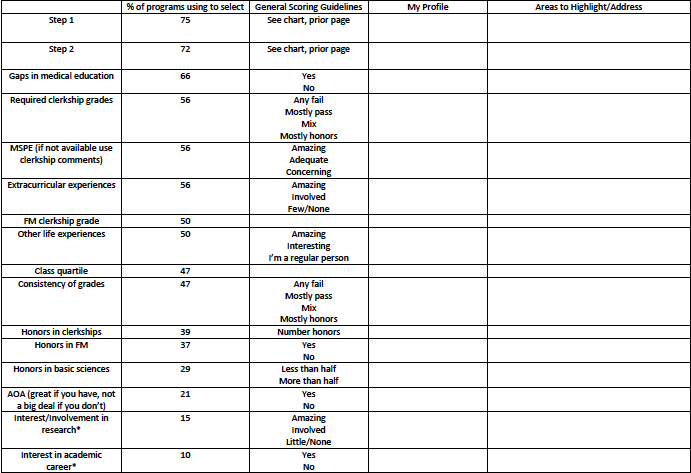

This exercise will help you give a rough estimate of how programs assess applications to decide how to offer interviews. It is not meant to make you feel bad about parts of your medical school experience; rather, it is designed to help you be objective about where you are in the applicant pool, so you can make informed choices about what programs to apply to and how long your rank list should be. This information is based on the 2010 NRMP Program Director Survey and is an average of the family medicine residencies that replied. It does not represent any individual program, nor does it represent every program, but it does offer a reasonable self-assessment you can do of your credentials.

NOT included on this worksheet are two vital pieces of your application. The personal statement is the most frequently used by programs to decide whom to interview with 76% of programs using it. Letter of recommendation is the fourth most frequently used with 70% of programs using them to screen applicants for interviews. This highlights the importance of your personal statement and your letters of recommendation. Also not included are two freebies you get just from having attended UW – going to an allopathic medical school that is also highly regarded.

NOT EVERYONE USES STEP 1 and 2 SCORES TO DECIDE WHOM TO INTERVIEW AND RANK. However, for those that do, this information can help you assess your competitiveness. FAILING STEP 2 IS MORE CONCERNING THAN FAILING STEP 1!

The other scoring guidelines are not based on any specific data but instead are a way of placing you in general categories. This allows you to identify strengths that you can play up and weaknesses that you should address in your application and interviews. There are many gradations between these large categories. For example, you may decide you belong somewhere between “amazing” and “adequate” for some areas.

References

National Residency Matching Program (2010). Results of the 2010 NRMP Program Director Survey.

National Resident Matching Program and Association of American Medical Colleges. (2011). Family Medicine. Charting Outcomes in the Match: Characteristics of Applicants Who Matched to their Preferred Specialty in the 2011 Main Residency Match, Fourth Edition.

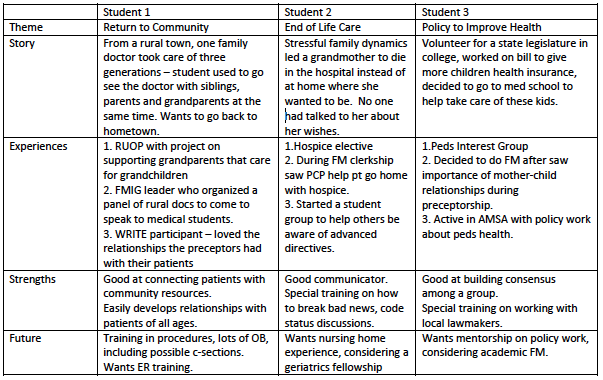

The best personal statements are memorable. They paint a picture in the mind of the reader and tell a story about who you are, how you got here, and where you want to go. The personal statement is vitally important because it is frequently used to help determine who gets interviewed and ranked.

Overarching theme:

Look over your CV and think about the experiences before and during medical school that inform what kind of family physicians you will become. Often there is a common thread that holds together even the most disparate of experiences – this common thread is usually one of your core values as a person. Identify this theme and write your personal statement so the reader could easily verbalize this theme in one sentence after reading your statement.

Experiences to highlight:

Use your experiences to give programs an idea of who you are. Be specific – talking about the aspects of care that you like in Family Medicine is good, but it’s even better when programs can see how your personal experiences reinforce aspects of family medicine that resonate with you as a person.

It’s okay to include patient vignettes and talk about your accomplishments, but be sure to relate it back to yourself. How did the experience impact you? What did you learn about yourself? How will the experience make you a better family physician? What about the experience demonstrates your commitment to the discipline of family medicine, your ability to work with others, your ability to work with patients?

Choose one experience and tell a story. This is a good way to open your statement, to develop your theme and make it memorable.

Commitment to specialty:

Talk about why you are choosing family medicine. Programs want to know why your’e attracted to a career in family medicine. What experiences convince you that this is the right field for you?

Strengths that you bring:

What do you bring to a program? What are you naturally good at? What specific skills do you have that will serve you well in residency?

Future plans/what you are looking for in a residency program:

At the end of this long road of school and training, what kind of work do you see yourself doing? What types of training do you want during residency to be able to accomplish this goal?

Organize your statement:

There are many ways to organize your statement to get these points across. One common way of organizing the personal statement is a three paragraph form reminiscent of those essays you had to write in high school. To use this approach the first paragraph tells a story to open the theme, the second paragraph fleshes out other experiences that highlight the them and discuss your commitment to family medicine, and the third paragraph reviews your strengths and future plans/training desires. However, this is a personal statement and you are free to write and organize it as you desire.

Do:

- Write in complete sentences.

- Use the active voice.

- Make your writing interesting – use a thesaurus and vary sentence length and structure.

- Have other people read your personal statement and give feedback.

- Give yourself plenty of time to work on your statement and revise it based on feedback.

Don’t:

- Rehash your CV or write an autobiography.

- Use abbreviations – spell things out.

- Violate HIPPA.

- Start every sentence with an “I.”

- Make it longer than one page, single spaced, 12 point font.

- Have spelling or grammatical errors.

- Write a statement that could be used for several different specialties (i.e. one that talks about wanting a primary care career but not specifically family medicine). If you are still deciding on a specialty and applying to different fields, write two different statements.

Sample Outlines for Personal Statement

Letters of recommendation are very important. Over 70% of programs use them to help decide whom to interview.

Who to ask:

- The minimum requirements for a letter writer are: someone who can comment on your clinical abilities AND who you know thinks you did a good job.

- At least one letter should come from a family physician. The other letters can come from physicians in any specialty. Additional letters from family physicians or other physicians in primary care fields can help strengthen your application by indicating your commitment to family medicine.

When you request a letter:

- Ask the individual if they would be willing to write you a “strong letter of recommendation.”

- Give the letter writer plenty of time to get your letter in, at least one month.

- Some letter writers may need gentle reminders about the letter. If a month has passed, send an email.

Number of letters:

- You should have a minimum of three letters of recommendation – some programs will accept more.

- Do not submit more letters of recommendation than a program accepts.

- Rarely a letter writer will not come through with a letter. Be sure to request at least one back-up letter to prepare for this. Nothing is worse than only having two letters in your ERAS application and watching the days tick by. Ask 4-5 people for letters to ensure you will have the minimum number required.

To get great letters of recommendation:

- Ask physicians who know you well for letters. You should ask for letters from physicians who have directly observed your clinical skills. Important things that residencies want to see in a letter include your clinical knowledge, your willingness to learn, your ability to work with other members of a team, and your ability to work with patients.

- Provide your letter writers with your photograph and a copy of your personal statement and CV. The photo ensures that the letter writer is writing about whom they think they are writing. The CV and personal statement gives the letter writer more information about you that can help them round out your LOR.

- Ask for letters as soon as possible. It’s easier for a letter writer to remember specific examples of your skills right after a clinical experience.

- Be sure your letter writers indicate your interest in family medicine. A letter that states that you would be a great resident without naming the specialty could be viewed as a “generic” letter and perhaps a sign that you are applying to two specialties in the match.

- Share these tips for writing a LOR when requesting a letter. LOR Writing Tips for Faculty 2021

Avoid these pitfalls:

- Asking for a letter from the chair of the Department of Family Medicine. Do not ask the chair to write a letter unless this person can directly comment on your clinical skills OR the program requires this letter. These letters are often just a rehash of the rest of your application and do not add more information. It is better to have letters that comment on your abilities based on direct observation.

- Letters that do not at all relate to family medicine. You may have demonstrated amazing surgical skills during your neurosurgery elective, however, most family medicine residencies will not be interested in your ability to perform a laminectomy. A letter from a neurosurgeon could be a good letter if it comments on your skills on the wards, in clinic, or on a team.

References

National Residency Match Program (2010). Results of the 2010 NRMP Program Director Survey.

There are many ways to structure your CV. As you prepare your CV, keep in mind that the goal of the CV is to communicate to programs your activities and accomplishments in a brief format. Most CVs list accomplishments in reverse chronological order. In general, it’s best to focus on activities and accomplishments from undergraduate, graduate, and medical school. Your CV should also clearly address any breaks you took in between these educational periods. Did you work? Did you do volunteer work? Were you involved in research?

Everyone’s CV looks different. Don’t worry about what you think should or should not be on your CV (ten different honors! president of three different organizations!). Make your CV reflect you – programs use the CV to get a picture of who you are and what is important to you through your participation in different activities.

Information you enter into ERAS will be formatted into a CV that programs can print out. However, since you are collecting all this information anyway, now is a good time to write/update your CV. Bring copies with you to interviews – it’s unlikely you’ll be asked for a copy but it never hurts to be prepared.

Many students wonder if they should include activities before medical school on their CV. Definitely include all awards and honors from college onward. Unless you did something unbelievably amazing in high school, leave these activities and awards from this part of your life off of your CV. It’s ok to include pertinent college activities for which you made a substantial commitment.

How to document your RUOP on ERAS:

- The RUOP experience itself goes into the volunteer section.

- If you did your III with RUOP, the resulting posters and abstracts go in the publication section.

- General citation for a poster: Last Name, First Initial. Title of Poster. Poster session presented at: Number and name of session; date of session; place of session.

- For the UW Poster Session: University of Washington School of Medicine Annual Medical Student Poster Session

- For the Carmel Conference:

- If you gave a Powerpoint Presentation, your abstract was published in:

Journal of Investigative Medicine, Vol. xx, (1) #–, January 20xx.

The number appearing next to your name in the “20xx Schedule” on the home page is the number of your abstract for inclusion in your journal citation. - If you presented your poster, include a poster citation with the name of the session (x Annual Western Student Medical Research Forum)

- If you gave a Powerpoint Presentation, your abstract was published in:

Do:

- Be honest.

- Include professional memberships. Remember how you joined the AAFP your first year? Put this on, it shows a commitment to the specialty!

- Be clear in ERAS about your leadership activities. If you were one of the two student leaders on a project organizing 50 medical student volunteers over 2 years then state that explicitly so people know exactly what you did.

Don’t:

- Pad your CV with many small experiences. A leadership position or participation in activity for 2-3 years means much more than 20 activities that just required you to show up once.

- LIE. Never ever lie. It will end badly.

The Interviews

Setting up Interviews

Different programs have different ways of assessing applicants and offering interviews. Some programs will offer interviews based entirely on a set of criteria that can be deduced quickly from an application (e.g. certain board scores, US senior applicant, etc.). These programs may get back to you very quickly (rarely in the same day as you apply). Other programs have faculty review each application and it can take a few weeks to get an invitation to interview. Almost all programs offer interviews on a rolling basis and schedule students as they receive and process applications. This is why it is important to apply to programs the first day you can. In 2010 over 50% of programs offered MORE THAN 50% of their interview slots between September 1st, when applications could be downloaded, and November 1st, when the Dean’s letters were available. Only 17% of programs waited to offer interviews to any students until November 1st. In 2012 programs offered 63% of their interview slots before the Dean’s letter came out. This is likely still true since the application was pushed back to September 15th and the Dean’s letter moved up to October 15th.

It’s a good idea to have a rough idea of what order and what weeks/months you would like for your interviews so when you get an invitation you can reply quickly to schedule. Once you are offered an interview, make sure you schedule it as soon as you can. Replying promptly to interview invitations is not only polite – it gives you a larger pool of interview dates from which to choose.

Residency program coordinators are very important people in your residency application experience. They are the people you will e-mail or talk to on the phone to schedule your interview and will likely be the first people to greet you on your interview day.

Order of Interviews

You will undoubtedly hear many theories on the best way to order your interviews. The most important strategy is to schedule interviews at your top choices in the middle of your interview season. This way you will be comfortable and familiar with the process of the interview without being exhausted. Also try to group interviews by geographic location so you do not have to visit the same city or area of the country twice. Most programs have set “interview days” (e.g. Tuesdays and Fridays), but there should be enough leeway in their schedule and yours so that you can schedule multiple interviews in one city over the course of a week or 10 days.

If You Have Not Heard From a Program

Consider sending them an email. It never hurts to check in if you think that you should have received an interview offer. If you need to travel and have already received an interview in one city but have not heard from programs in nearby areas, let them know that you’ll be traveling to their area for an interview at a different program and perhaps you could schedule an interview at their program too while you’re in town. If you send an email and do not hear back in 2-3 days, give them a call.

Dress for Success

This is a job interview in the medical profession and business attire is the accepted norm. You want to give the appearance of a successful, mature physician, not a medical student who has been up all night studying. You will need to buy a suit. Your outfit should be both conservative and comfortable. Make sure you can get it to appear neat, pressed, and clean, even after being in suitcase or being worn for 2-3 successive interviews. Be prepared for bad weather – always have an umbrella and overcoat with you.

When selecting an outfit:

- Choose dark, conservatively colored suit – solid or pinstripe are acceptable. Women can wear either a skirt or pants.

- Choose a lighter, conservatively colored shirt. Men should wear a button-down shirt, women can wear the same or a blouse or light sweater.

- Wear simple, comfortable dress shoes that you can walk in easily to tour clinics and hospital.

- Men should wear a tie. Choose one that is also conservative and is solid, striped or has a small pattern.

- Men should have well groomed facial hair.

- Make-up for women should be subtle.

- Avoid strong smelling perfumes or cologne.

- Keep jewelry tasteful and to a minimum.

Coordinating Travel

Make sure that your travel arrangements leave you plenty of time to attend any pre or post-interview social events. If you are driving, be sure to leave plenty of time to arrive at your destination and make sure the vehicle you take is in good repair and has been serviced recently. If you are flying, make sure that all of your belongings fit into a carry-on bag. You do not want your aforementioned, meticulously selected suit to not make it to the interview with you. If you are renting a car, be sure to reserve one ahead of time before you arrive to the airport. To help defray travel costs check out HOST (Help Our Students Travel), which is sponsored by alumni who will let you stay in their homes while interviewing in different cities.

http://depts.washington.edu/medalum/migration/forms/host-student.php

Canceling Interviews

If you need to cancel an interview, emailing the program coordinator is appropriate when done with advanced notice. Call the program if you’re canceling close to the date or to follow up if you receive no email response. This way the program can give your interview slot to another applicant.

Do:

- Do respond to the program in a timely manner regarding acceptance/decline of interview or any special events, including pre or post interview dinner.

- Do contact the program promptly if you need to cancel your interview

Don’t:

- Wear khakis, or a sport coat, or really anything that is NOT a suit.

- Cancel your interview the day before the interview.

References

National Residency Matching Program (2011). Results of the 2010 NRMP Program Director Survey. 49.

For each program you will have general things you want to assess as well as things specific to the individual program that you want to explore.

General Attributes

It is good to come up with a comprehensive list of attributes you want to assess for each program. To figure this out you will need to determine what you want in a residency and associated community. Place for educational excellence. These are three formative years in your training and it is vital that you receive quality education.

Some common factors students assess of a residency include:

- Volume of patient contacts – enough to learn and become more efficient without being overwhelmed?

- Diversity of patients – this includes types of patients (peds, OB, adults, etc.), background of patients, types of visits (acute, preventive, chronic disease).

- Supportive learning environment in which the resident is challenged yet has the support structure to learn. Balancing these two will be variable between different residents; you must find a place that will fit your style and needs.

- Hospital and clinic size – will you be more comfortable learning in a small community hospital or in a tertiary care center? In a stand-alone clinic or in an integrated, multispecialty office?

- Collegial learning environment – is the resident part of a team of learning?

- Emotional support – how does the residency prevent burnout and address residents in trouble emotionally and academically?

- Good fit – the feel for the place and the people you meet. Are these people you want to spend three years with? In the end, the general feel fo the place affects deeply the choice of residency. This is an important part of residency selection.

- Graduate success – are the graduates of the program successful and doing what you want to do when you are done?

Some common factors students assess in a community include:

- Social connections – churches, activities

- Needs of children – childcare, schools

- Needs of significant others – employment/educational opportunities

Below is a list of factors that students who matched in family medicine reported as important to them in ranking programs highly. Use this as a guide to create your own list.

Specific Program Attributes

It’s also good to have some things that are specific to an individual program that you want to explore. To develop this list you first need to do some research:

- Review all the information a program sends you.

- Visit the program’s website – review the program’s mission statement and their goals.

- Research the faculty.

- Research the residents.

- Consider contacting any UW graduates in the program.

To prepare for the individual interview experience:

- Ask for an interview schedule ahead of time if it was not included.

- Ask the program what to expect and what materials to bring for the interview day.

- If you know who will interview you, research those individuals more carefully through the website. Consider searching for them on Pubmed and FMDRL (Family Medicine Digital Resource Library).

Prepare Your Questions

Based on the needs and wants you identified above, brainstorm a list of information you wish to find out during your visit. Prepare a list of questions for residents, faculty, and staff.

- Have a list of different questions for different people. You will want to ask the program director very different questions than you ask the staff.

- Prepare questions you can ask to draw out the information you want from the interviewer.

- Avoid general questions like “What are the weaknesses of the program?” Instead, try to ask about specific information you want to know about the program. For example, “what is the pediatric inpatient volume in the residency” “How many deliveries does a resident typically have at the end of residency?” “How independent is a resident in the inpatient service?” “How is supervision in the clinic done?”

Below is a list of possible questions for each group of people you interact with.

Program Director

- What is the success of graduates: board scores, finding jobs/fellowships?

- Accreditation?

- Status of the program and hospital: Have any house staff left the program?

- Quality of the current residents? Have any left the program recently?

Faculty

- What are the clinical, non-clinical, and administrative responsibilities of the residents?

- How are residents evaluated? How often? By whom? How may they give feedback?

- Are there research or teaching opportunities?

- Do you foresee any changes in the next three years?

Residents

- What contact will I have with clinical faculty?

- How is it working with the faculty?

- What is the average daily workload for interns? Is it varied?

- How much didactic time is there? Does it have priority?

- What types of clinical experiences will I have?

- What is the work schedule? Call schedule?

- What is the patient population I will see?

- Are you happy? Was this a good match for you?

- Do the residents socialize as a group?

- Are there moonlighting opportunities?

- How competitive was it to match to this program?

Staff

- What is the rotation and call schedule like?

- What are the parking and transportation options?

- How does the residency schedule electives and away rotations?

- What is the city/town/area like?

- For residencies that have specific tracks – what are they like?

- What residents and faculty should I talk to about my interest in X (OB, sports med, etc.)?

- While on call, what do residents get in terms of meals and call rooms?

Questions Not to Ask

These are topics you should typically not ask about during the interview. Most of this information will be in the packet they send you or covered in an introductory meeting. If not, they can be addressed in a follow-up email to the program coordinator, who will probably connect you with an HR representative.

- Salary

- Benefits

- Vacation

- Family Leave

Do:

- Your homework before the interview. Know something about the program, the people, and the director.

Don’t

- Select a residency based on their pay rate. If you are truly strapped and can’t live without the difference in pay from one residency to another, only then should this be a consideration. However, when you are out of residency 10 years, the few thousand extra dollars will likely seem much less important than they do at the time of entry into residency. You will certainly feel the pain after residency if you have not met your training needs.

- Fixate on one thing during your interview (one particular accomplishment, one aspect of the program, etc.)

National Residency Matching Program (2011). Results of the 2011 NRMP Applicant Survey by Preferred Specialty and Applicant Type. 27-28.

Prepare to answer all types of questions during your interviews, including very open-ended ones and ones that may probe weaknesses that appear on your application.

Know Yourself

- Make a list of your top strengths, goals, values, accomplishments, and abilities to use as a general reference for all interview questions.

- Develop your TOP 5 list. Go into every interview with 5 key things you want a program to know about you. What makes you a good candidate? What makes you unique?

- Know your weaknesses. If you encountered academic difficulty you will probably be asked about it at least once during your interview. Know what you will say ahead of time and reframe it in a positive light. (Example: My father became very sick a few weeks before I took step 1 and I did not pass on my first attempt. I learned from this experience how to manage my education even in the face of personal difficulty. Though he was still sick when it came time for step 2, I passed the first time I took it.)

What Interviewers May Ask

Prepare to answer the most common question: “What questions do you have for me?” Many residencies want to see that you’ve thought carefully about their program and that you’re applying to them because you are interested in the unique things their program offers. This is your opportunity to let them know you’ve done your homework.

Make a list of potential questions you may be asked. Practice your answers ahead of time. The following is a list of potential questions that may aid you in your preparation:

- How are you today? (there are NO innocent questions)

- Tell me about yourself.

- What are your strengths and weaknesses?

- Why are you interested in this specialty? (#1 question asked)

- What other specialties did you consider?

- Why are you interested in our program?

- What are you looking for in a program?

- Where else have you interviewed?

- Why should we choose you?

- What can you contribute to our program?

- How well do you feel you were trained to start as an intern?

- Describe your learning style.

- Tell me about… item(s) on your CV or transcript, past experience, time off, etc.?

- Can you tell me about this deficiency on your record? (Do not discuss if you are not asked)

- What do you see yourself doing in five (ten) years?

- What do you think about… the current and future state of healthcare, this specialty, etc.?

- What do you do in your spare time?

- Present an interesting case that you saw during medical school.

- Tell me about a patient encounter that taught you something.

- What would you do if you knew one of your more senior residents was doing something wrong (e.g. filling out H&P’s without doing the evaluations, tying someone’s tubes without consent, etc.)?

- Which types of patients do you work with most effectively? Least effectively?

- How do you make important decisions?

- If you could no longer be a physician, what career would you choose?

- How do you normally handle conflict? Pressure?

- What do you think about what is happening in… ? (non-medical current events question)

- Teach me something non-medical in five minutes.

- Tell me a joke. (Keep it simple and tasteful)

- What if you do not match?

- Can you think of anything else you would like to add? (Always add something!)

- What is your vision of yourself in FM as a specialty?

- What do you think will be difficult for you in residency and how do you cope with it?

- Who are your role models and how did they affect the way you want to practice medicine?

- How do you see yourself being involved in health reform?

There are some questions that are not allowed during interviews. If you are asked one of these, you can simply reply that you are not comfortable answering that question. “Illegal” questions might include:

- What are your plans for a family?

- Are you married? Have any children?

- How old are you?

- If we offered you a position today, would you accept?

Prepare Your Two-Minute Drill

This is a great response to an open ended question like “Tell me about yourself.”

- First fifteen seconds is a brief review of who you are (My name is _____. I’m originally from ____, and I’m attending the UWSoM).

- The next thirty seconds is a review of your educational background, undergraduate degree, work experience, and life experience.

- The next thirty seconds is a review of special attributes from medical school, such as leadership positions, family medicine experience, or other experiences that led you to the decision for this specialty.

- Final fifteen seconds is a review of why you’re interested in this residency specifically and what attracted you to this place here and now.

- Optional closing if this question does not occur during the interview: “Tell me more about the residency or about your position with the residency.” This leads the way for the interviewer to introduce him/her self and the residency.

This is intended as an icebreaker that gives the interviewer enough information about you and your background and interests to start a longer conversation. Make this two-minute drill personal; you don’t need to follow the suggestions above exactly. In practicality, you may have 10 minutes of material that you have memorized and rehearsed that will allow you to mold the two-minute drill to any situation. The two-minute drill doesn’t have to be done in order from top to bottom. For instance, you may be introduced by another, then you can start the drill and skip the first fifteen seconds.

Mock Interviews

Do a mock interview. A mock interview can be done by family or friends, your advisor or mentor, or through the Family Medicine Department. Plan to treat every interview as though it counts and do not use your first interview as “practice,” because you may find that you really like the program. Prepare as if it were a real interview: review your answers to specific questions, have a list of questions you plan to ask, and if possible, dress as if it were a real interview.

Do:

- Be prepared to address any potential red flags in your application, including extension of training, USMLE failure, or course failure. Programs are checking to see if you have insight and have taken action to correct the problem. Honesty is much preferred over defensiveness or excuses.

- Practice the length of your responses.

Don’t:

- Talk for too long (aim for a few minutes per question max)

- Go off on tangents

The purpose of the interview is for both parties to learn about each other to determine if the applicant and residency are a good fit. This is a time for you to get to know them and for the residency to get to know you. It is an opportunity to learn and explore.

The entire experience is the interview. If you are with someone from the program – staff, faculty, or residents – you are being interviewed. Any one part of the interview process can make or break your chances of getting into the program.

Pre-Interview Events

The dinner and social hours that residency programs hold before interview day are a great way to learn more about the program and get a feel for the residents and faculty who may be interviewing you the next day. Even though this will be a more informal event, remember that your interactions during these pre-interview activities will be included in the program’s discussion of you after you’re gone. Go to social events. You may be tempted to skip, but you will miss out on valuable information. Also, some programs won’t rank students who do not attend the social events as they see it as a sign that the student is not really interested. If it will be difficult to get to a pre-interview event due to travel (for example, if your flight lands at 8PM the night of the dinner), let them know that you are sorry that you will be unable to make it due to your travel schedule.

What to Bring

Carry copies of your CV, personal statement, and transcripts, your lists of questions you wish to have answered, and a note pad with you as you would for your interview (use a nice portfolio). Bring outerwear for bad weather and breath mints for after lunch.

Getting to the Interview

BE ON TIME. This cannot be over emphasized. If possible, go to the building prior to the interview so you know where to go and how to get there so your travel on the interview day will go smoothly and allow you to get there on time. If you cannot practice getting to the interview site before your interview day then leave plenty of time in case you get lost or encounter other travel difficulties such as construction, public transit delays, or parking issues.

Shining in the Interview

For the actual face-to-face interview, make sure to make eye contact, shake hands, smile, introduce yourself, and if you’re asked the open ended question, “tell me about yourself,” use your two-minute drill. Questions can be repeated from interviewer to interviewer. Most of the time the interviewers don’t talke with each other until after the interview day is over and won’t know anything about the interactions in a previous interview. Try to sound fresh and positive even if you have answered that same question 5 times. Your questions will change depending on whom you are talking with. For example, residents will know more information about call schedules and the intricacies of different rotations. Prepare a group of questions for each time of interviewer – resident, staff, faculty, and the program director.

Make sure to:

- Not ramble.

- Listen to the questions asked, and understand what is being asked, and answer the question that was asked.

- Not answer a question they did not ask or add too much loosely-related information.

- Be comfortable with pauses, silence – stay poised and confident

- Sound fresh every time – be prepared to answer the same question 20+ times throughout the entire interview process.

- Smile! It’s highly underrated and often forgotten when nervous or tense.

Shining Throughout the Day

Remember that you will be “on stage” for the entire day. Treat everyone with respect; everyone you meet before the interview and on the interview day will be involved in the decision about your application to the program. All staff, including receptionists, nurses, and the folks who answer your phone calls and emails, have a voice in the resident selection.

Interviews are draining emotionally and physically. Maintain energy and interest throughout the entire day. If you need a minute or two away to regain your brain, excuse yourself to the bathroom, get a drink of water, or find some way to get a minute or two by yourself.

Accept invitations for future contact. If residents offer you their cards, take them. You can send them an email later to let them know how much you appreciated their time and ask any lingering questions. Take faculty member’s contact information when offered and reconnect with them to let them know mow much you appreciated their time.

What does a residency look for in an applicant?

The following is a partial list of things programs look for in applicants during the interview:

- Knowledge base

- Academic progress

- Initiative – self-motivation is an important part of being and learning as a resident

- The ability to recognize one’s own limitations or knowledge gaps. The program wants residents that can recognize and find a solution to a knowledge gap or limitation in a specific ability to perform a skill. This becomes the task of accurate self-assessment, which is a lifelong process of being aware of one’s knowledge and one’s limitation.

- Motivation

- Personality – warmth, caring, compassion, maturing, self-awareness

- Ability to work under stress

- Commitment to work and get the job done

- Maturity

- Fit with the goals fo the program

- Fit with the residents and staff at the program

- Reliability. Is this an individual I can trust to take care of patients at night when no one else is around? Will they get help when they need it? Will they care for patients on their own? Will they get done what they say they will do? Will they treat others around them, including staff and patients, with respect? Will this individual be able to do the job?

Listed below is what the program directors reported on the 2010 Program Director Survey as what the program uses to rank applicants, in order of importance. Note that interactions with faculty and residents are the top factors used to rank applicants for the match.

Do:

- REMEMBER THAT THIS IS A JOB INTERVIEW

- Ask thoughtful questions about the program.

- Talk intelligently about family medicine and why it’s the discipline for you.

- Be genuin.

- Feel free to follow up and ask for faculty and resident contact information. You can use this information to send thank you letters and ask questions you forgot to ask during the interview.

- Make eye contact with your interviewer and use nonverbal cues to show that you are listening to your interviewer.

- Treat the staf with the same respect you do the residents and faculty.

- Act professionally during your interview.

- Prepare for the trip: look at a map, visit websites that will give you information about the community and surrounding area. Know where you’re going – if you’re unfamiliar with area, don’t assume similarity of geography or climate because of how near or far it looks on the map. Make travel plans accordingly.

Don’t:

- Don’t openly compare the program you’re interviewing at with other programs in town.

- Don’t be rude to staff.

- Don’t spend the day asking for special favors such as asking the program coordinator to run an errand.

- Don’t interview if you’re not interested in the program.

- Don’t obsess over getting parking validation for the interview.

- Don’t slouch during your interview.

- Don’t use your cell phone during the interview. Even if you’re only taking notes, it looks like you’re not paying attention.

- Don’t ask questions that are easily answered by looking at the program’s website.

- Don’t be ingratiating with faculty or the program director.

- If your spouse or partner accompanies you to a social event, do not engage in public displays of affection.

- Bringing infants and small children is not advisable as they can disrupt activities.

References:

National Residency Matching Program. (2010). Results of the 2010 NRMP Program Director Survey.

After your interview you will have a lot of information that you will use to determine the program’s rank on your rank order list. You may also decide you need additional information for programs you are very interested in.

Reflect on the Interview

After your interview you will need to figure out how much the residency impressed you. As soon as possible after the interview, take time to write down your thoughts and impressions. Ideally this would be done the next morning, after your head has cleared from the interview day but when you still remember lots of details. You will also want to write down any further questions that may come up after the interview day and a list of contact information of residents and faculty who said they would be willing to answer follow up questions.

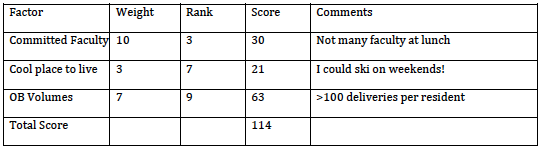

Students employ various methods of determining how impressive they found an individual program. Most people use some combination of a scoring sheet and their gut reaction to the program. It is important not to rely too heavily on either one – the overly analytical or the overly instinctual. When it comes to make a rank list, students do best if they keep both in mind. This way, you won’t be swayed by a single charismatic resident at a program tat does not really meet your training needs, nor will you go to the residency that got the highest score but where you did not feel a good connection with the current residents.

Sample residency Scoring Sheet – Residency XYZ:

Contact after the Interview

Always send thank you cards to your interviewers. This means an actual piece of paper, not an email. If you do have questions that come up after your interview, contact the residency or faculty who gave you their information.

A second look is a half-day or day that you set aside to come back and visit programs that you are most interested in. It clearly communicates to the program that you are interested and it allows the program to get to know you outside of the interview day. You should contact the program coordinator to see if they will help you to set up a second look.

Do:

- Send thank you cards in a timely fashion.

- Take time to really reflect on your interview day.

- Consider a second look for one or two programs you are really interested in and are having trouble deciding between.

Don’t:

- Send an administrator a single envelope full of thank you cards to distribute to your interviewers.

- Send an email to a resident or student with 10 questions that would require 3 pages each to answer. Residents and faculty are busy. One or two easily answered questions are fine, but if you require more than what can be typed in a few minutes it is better to see if someone can speak with you on the phone.

- Schedule a second look at every program.

If you get emails from residents or faculty that you met while interviewing at a residency, send them a prompt, polite email in response. You might get multiple emails from different people in the same residency asking if you have further questions; they are trying to reach out and are not necessarily aware that their colleagues are also in touch with you! Feel free to ask any questions that you might have, but it it is also acceptable to let them know that all of your questions are answered for now and that you will let them know if anything else comes up.

Rank Order List

Here are some general guidelines to follow when creating your rank list:

Rank the programs in the order that you want to attend. This means the program you like bet is ranked first, followed by your next choice, then the next. This seems simple, but people often try to somehow “beat the system” through other ways of ranking (for instance, ranking programs in the order of what the student thinks they are most likely to match). Do not try this; you cannot outsmart the match algorithm. You are most likely to get your top choice of residency if you actually put that program at the top of your list.

Rank all programs you are willing to attend. Before you leave a program off of your list, ask yourself if you would rather scramble than attend that program. Certainly there are some programs that are such a poor fit for someone that they should be left off. This is usually rare and is likely limited to 1-2 programs per person. If you find yourself axing 5 or 6 programs, seriously consider how bad it really would be to attend these programs versus one you scramble into.

Longer is better. A longer match list means you are less likely to go unmatched. Make your list as long as possible. In general, this means your match list is the same number as the places you interviewed, maybe minus one or two programs you really could not stand to attend. Don’t rank just one program.

TALK IS CHEAP. There is a reason this is in capital letters. Do not believe anything a program says about promising you a slot or placing you high on the match list. This is not because the people you are talking to from the programs are lying or trying to take advantage of you. Interviewing for residency is a lot like a few first dates – both sides are trying to look good to the other and gauge how interested the other party is. It means that what words you exchange with a program are just words. There is no assurance that anything will come from this conversation. Do not base your rank list on verbal assurances, base it on your desires for what you think is the best program for you. This is one time in life when you get to be completely selfish. Enjoy it!