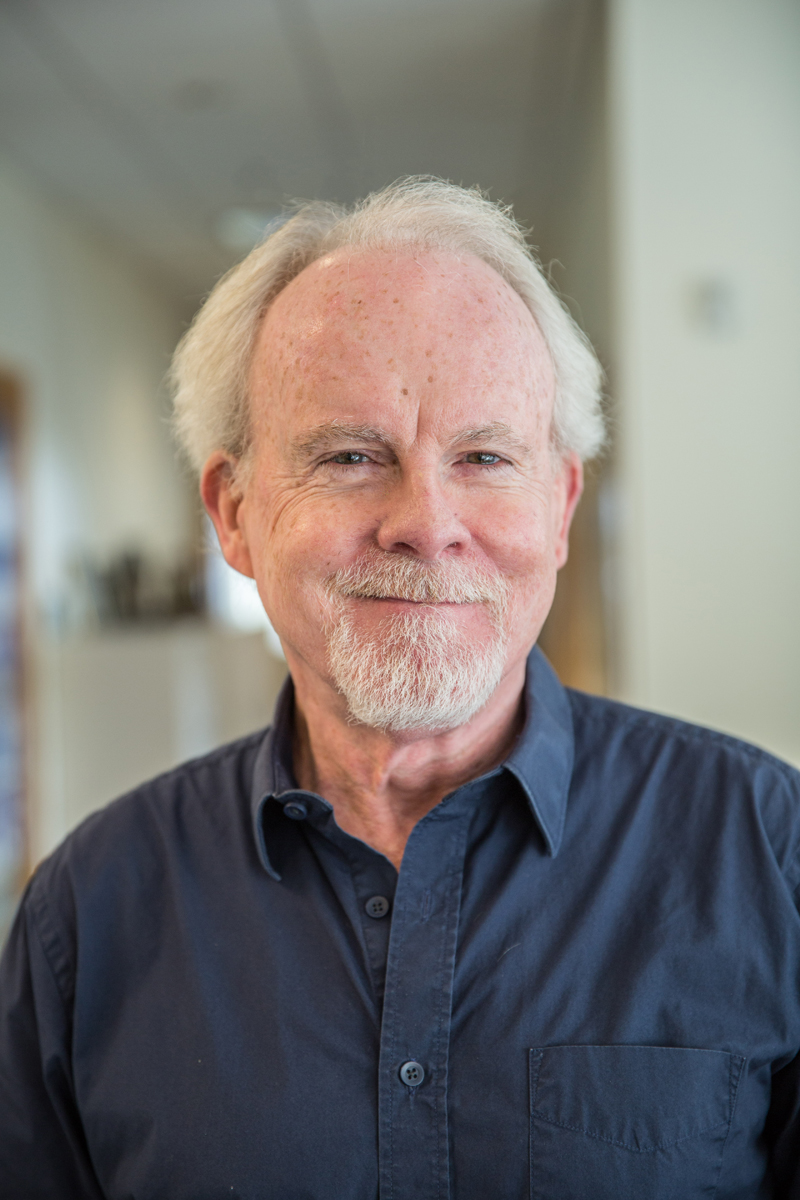

Tim Quigley, MPH, PA-C teaches behavioral medicine at the MEDEX Northwest physician assistant program. Away from the classroom and in their clinical year, MEDEX students often comment on how much they encounter mental health issues with patients during their required 4-month Family Practice preceptorship. They also mention how Tim Quigley’s classes prepared them for these patient encounters.

“Behavioral medicine is a big part of primary care,” Tim explains. “We’re not educating PAs to be psychiatric PAs. We’re training primary care PAs to treat depression, anxiety, bipolar or psychotic disorders, insomnia, abuse, trauma and all that.”

In response to a shortage of treating practitioners, the Washington State Senate passed Senate Bill 6445 in early 2016, thereby clearing the way for PA positions at psychiatric hospitals.

More than most, Tim Quigley knows the importance of this scope expansion for physician assistants into behavioral medicine. He comes from a long history of employment in the largely underserved sectors of society. Not all of it was as a PA, however. During the fledgling years of the profession, jobs for PAs were scarce. This led him to gigs with the United Farm Workers and a maximum-security prison.

But, before all that came to be, it’s interesting to know something about Tim’s roots, and how this set him up for a life of service.

First Job

“My parents were volunteers and most of us grew up doing some sort of service work as kids,” he says. “My church was pretty progressive and we were all heavily involved in the Catholic Church which was down the street from us at that time. There was that spirit of volunteerism, giving back to the community and service to the poor. It was kind of a family ethic.”

At the age of 16, Tim set out on a job search so he might contribute to the family household of 11. He had no idea where to start.

“I went to the drug store, I went to the hardware store,” he tells us. “I just kind of wandered around like a kid does trying to find a job, but wasn’t getting anywhere.”

There was a nursing home located on a busy street on the outskirts of his neighborhood.

“I never paid much attention to it,” he tells us. “But I thought, I could cut their grass or shovel their snow—something like that.”

“I never paid much attention to it,” he tells us. “But I thought, I could cut their grass or shovel their snow—something like that.”

Tim went into the nursing home, introduced himself, and was brought before the Director of Nursing. She looked him up and down, and asked, “Do you have any white clothes at home?”.

That night the 16-year-old went to JC Penny’s and bought a white pair of jeans. “I already had a white shirt,” he adds.

Dressed in the proper uniform, Tim started his first job the very next day as an orderly at an Indianapolis nursing home.

“It wasn’t just your average nursing home,” Tim tells you. “This was basically a county-funded nursing home that was filled with residents who were mostly very low functioning, formerly homeless people, people that had been released from prison, old people that had been released from mental hospitals, or elderly street alcoholics. It was a mixture of the mentally ill, homeless, criminals, and drug-addicted folks—a fascinating bunch of characters.”

Tim says this last statement without a hint of irony.

Before long, he was washing dead bodies, preparing them for the funeral home.

“I was sitting with people dying, or waking them for breakfast in the morning only to find them dead. I mean, this was very odd stuff for a sophomore in high school to be dealing with.”

Even under those circumstances, Tim doesn’t recall the orderly work as being an emotional burden.

“I remember feeling privileged to be there for these events in people’s lives,” he says. “It was so different from my upbringing, where I grew up in a middle-class white Irish Catholic neighborhood. This was a whole different part of society that I really had not been exposed to in any real sense.”

For all his time at the nursing home, Tim was one of the few white people employed at the institution. “So there again, it was an exposure to the poor African-American and immigrant community who were living completely different home lives than I had with my family,” he says.

College

While attending college in Southern Indiana, Tim continued to work at various nursing homes. “There was always a need for a healthy young man to do the physical work,” he says. Tim continued to work nights, weekends and summers while studying as an English and philosophy major.

Night shifts at the nursing home were quiet. “There’s not much going on at all,” he says. “You’re turning people, feeding others, answering some light calls.”

Night shifts at the nursing home were quiet. “There’s not much going on at all,” he says. “You’re turning people, feeding others, answering some light calls.”

So, as a curious guy, Tim would review the patient charts—their diagnoses, their treatments, their medications, their procedures, and their entire past medical history, right there on paper. He’d research patient conditions using the Physician’s Desk Reference and the Merck Manual.

“I’d try to figure out a cardiovascular incident,” he says. “If a patient had a stroke, why were they taking this medication? Or what was it supposed to do?” Tim became increasingly interested in medicine.

In 1972, Tim happened upon a story in American Legion magazine about a new medical profession that was starting up—physician assistants. There was nothing in the story about Indiana University, but Tim called the Indiana University Medical School. They told him, “Well, you know, we just happen to be starting a program.”

PA School

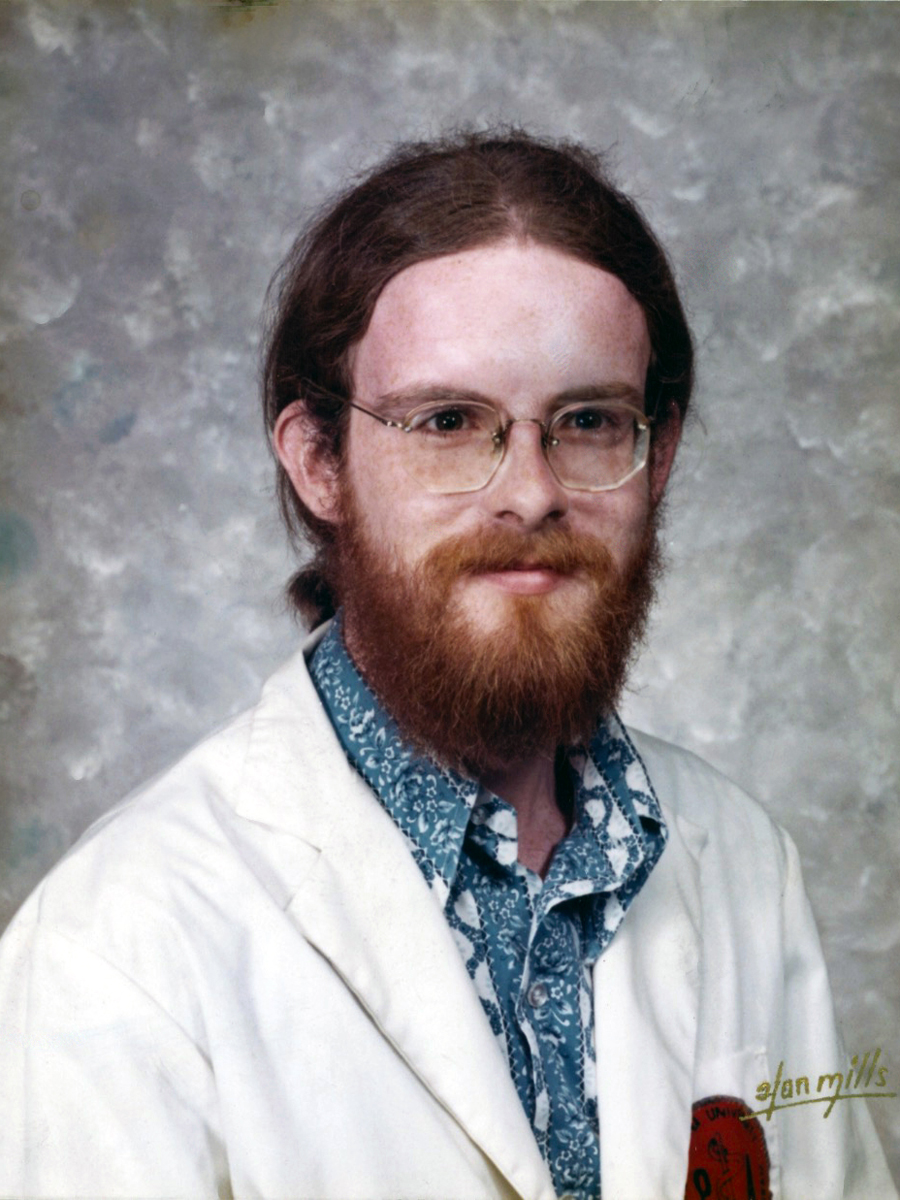

With a phone interview, Tim Quigley was admitted into Indiana University’s inaugural PA program. “There was no competition to get in during those days,” he says. The class consisted of 12 students, and half were Vietnam veterans. In contrast, Tim was the sole war resister.

“There was a big cultural gap between me and the rest of the class,” Tim says. “There were combat medics and a couple of women who were trained nurses. I was the token hippie orderly.”

There were no visible PAs in Tim’s world at that time.

“I had never heard of a PA before, and there weren’t any in the state of Indiana,” Tim says. Indiana University brought in a new graduate from the Cleveland Clinic’s PA program to run their PA program. “He was the only PA any of us had ever met.”

There was no national certification exam when Tim graduated from the Indiana University PA program in 1974, but he had to return one year later for a board exam. “The exam wasn’t there when we graduated. In addition to a lengthy paper exam, one had to perform a physical exam with a mock patient while a faculty would proctor and grade you.”

United Farm Workers

Back in the mid 70s, the Vietnam War had wound down, Nixon had resigned, and Tim Quigley was out of PA school. There were no PA jobs in the Midwest outside of PA school. Only one out of Tim’s twelve classmates had secured a job upon graduation, and that was because he was a former certified lab tech who found employment in that same field. Tim decided to travel down to New Orleans, where he had family.

At that time, the American Public Health Association was holding its annual conference in New Orleans. “I’ve always been a public health guy,” Tim says.

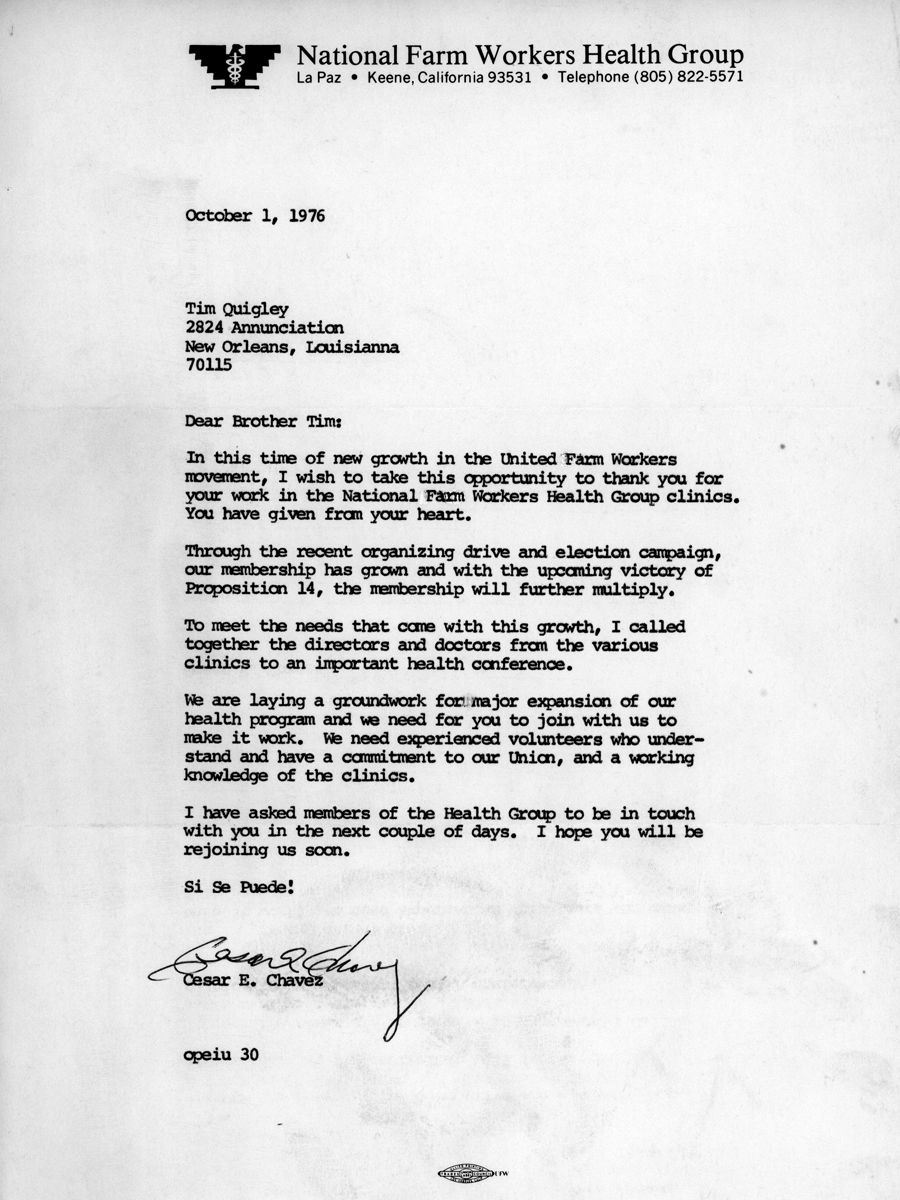

One of the main speakers at APHA conference was Dolores Huerta, who was second-in-command behind Cesar Chavez of the United Farm Workers.

Huerta gave a stirring keynote address in which she encouraged clinicians to volunteer for the United Farm Workers. “I was pumped up about it. I walked up to her afterward and said, ‘I want to do this.’ She gave me the phone numbers to call, and before long I was in a driveaway car to Central California.”

The UFW had a free-standing clinic on the grounds of what they called La Paz where Cesar Chavez had his home, offices and an assembly hall. This was a modern clinic with its own lab, x-ray, and a two-bed infirmary. All the patients were farm workers and their families. The lettuce and grape strikes were in full force at the time, so almost all of the farm workers were living in their vehicles instead of the employee labor camps.

Tim and his fellow clinicians were providing healthcare to the striking laborers. Not only were they expected to be medical professionals but union activists as well.

The UFW gave the striking laborers a small weekly check, same as Tim. “We got $15 a week and I lived with seven women in four bedrooms at Cesar Chavez’s old home in Delano, CA. We were basically like Peace Corps volunteers. It was fun.”

One incident stands out for Tim.

He was the new guy at the La Paz clinic, and drew the short straw to work on Christmas. On Christmas night, Tim was onsite with patients in the two beds. One bed held an elderly man who was dying, hooked to IVs to control the pain. In the other bed was a pregnant woman actively in labor.

“She had her baby on my shift,” he says. “I had somebody come in and help me. We did our own childbirth there, but I had never done a birth solo.”

The newborn was named Jesus, born on Christmas day.

Through all this, Tim still didn’t have a paying job as a PA. “A real job, you know,” he adds. “I was living on food stamps. We’d pool our $15 together and buy groceries.”

Prison PA

After six months with the United Farm Workers, Tim was called back to Indiana where his father was ill. Back home, he sought out work as a PA, but nobody there knew what a PA was.

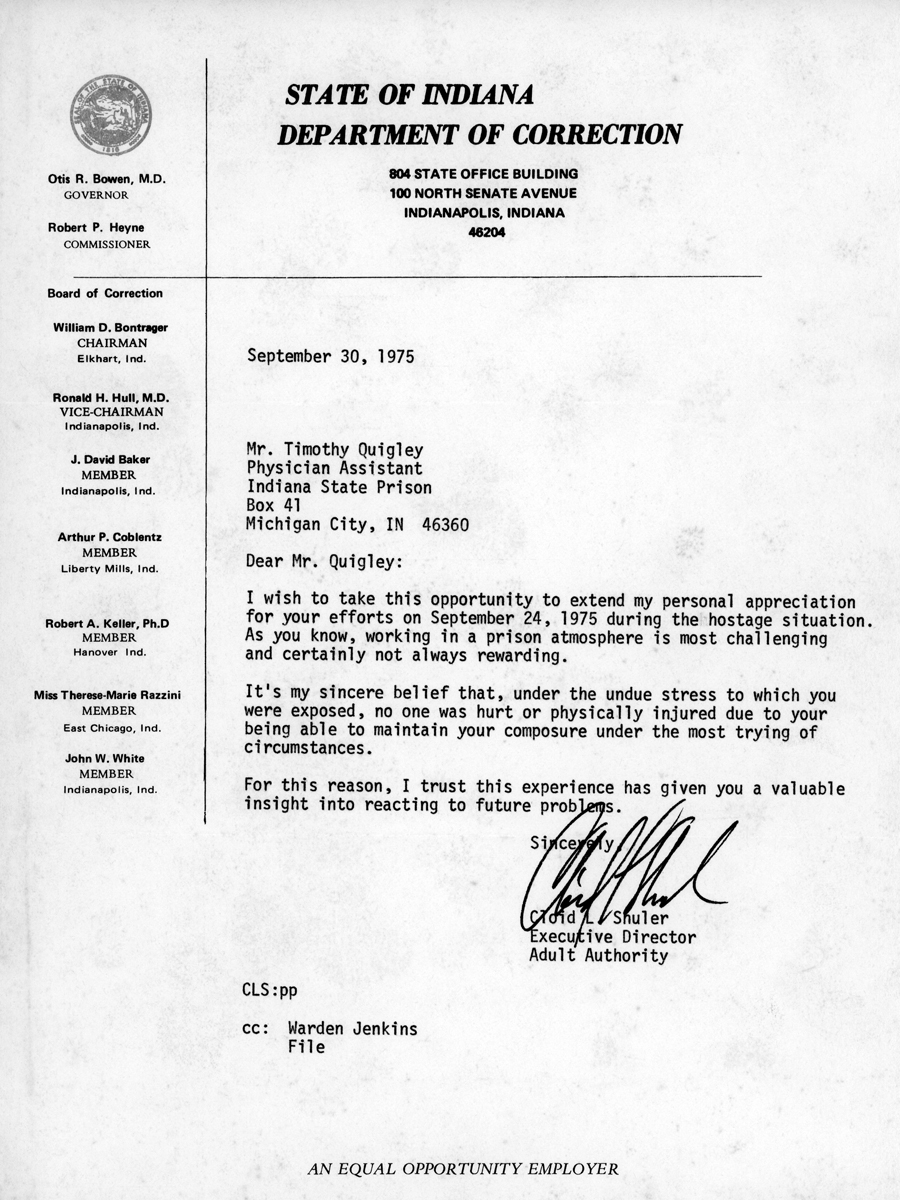

At that time there was a crisis in the Indiana State correctional system. Inmates had filed a federal civil rights lawsuit contending that their civil rights were being violated because of the low quality of medical care in the prison. A federal judge had ruled for the state to dramatically improve the prison medical system. Authorities were scrambling to hire people, and Tim turned out to be in the right place at the right time.

Tim’s job was to be a PA provider, but also to work on new policies and new procedures, ways to clean up the clearly felonious medical care up to that point.

Part of the reason for this reputation was that the prison underpaid physicians. Consequently, the quality of medical care in the Indiana State correctional system dropped to a lower tier of healthcare providers. Some of the physicians had their own criminal records, came from another state where they couldn’t return or had just gotten out of rehab. Some were still actively using or had mental health issues that impacted the quality of their care.

“These were doctors at the end of their rope,” says Tim.

Because of this, Tim was among those hired to turn the failing system at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, IN around. “This was a maximum-security facility, pretty much full of lifers, mostly murderers, rapists and the like.”

On September 24, 1975, during a meeting of the prison medical staff, two prisoners overwhelmed an elderly guard with a knife at his neck. They burst through the medical clinic’s conference room door threatening to kill the guard unless the medical team cooperated.

“They knew the hierarchy,” Tim says. A physician named Roger Saylors, along with Tim, was the highest-ranking medical providers at the clinic. Soon the prisoners had their knives directed at Tim’s and Roger’s necks.

“It was all about drugs,” Tim explains. The prisoners wanted to get high and were after the pharmaceuticals kept in the hospital under lock and key. The New York State Attica prison riot from 1971 was fresh in everyone’s mind. A number of people had been killed during that incident but, in this case, “there was really no political context to our being taken as hostages.”

Gradually, the prisoners let some people go, including the security guard and a diabetic in need of insulin. “We were only about four or five at the end, but they always held a knife on somebody to keep everybody else in line,” Tim recalls. “We did our best to keep calm and kept talking to each other.”

“Be cool, be cool, be cool. Give them what they want, give them what they want, just give them what they want.”

With knives at their necks, Tim and Dr. Saylors unlocked everything and gave the prisoners free rein of the pain pills, anxiety pills, sleeping medication, and other narcotics. “They were just thinking short term,” adds Tim. “We helped tie up their tourniquets. We helped inject them.”

At the start of this incident, the entire prison went into lockdown with everyone in their cells. Soon, there was a show of force. The State Police, technical response and an emergency team were in place.

“So, here we were, in this room with windows on both sides. We soon realized that the rooftops were filled with police snipers’ guns pointed at us.”

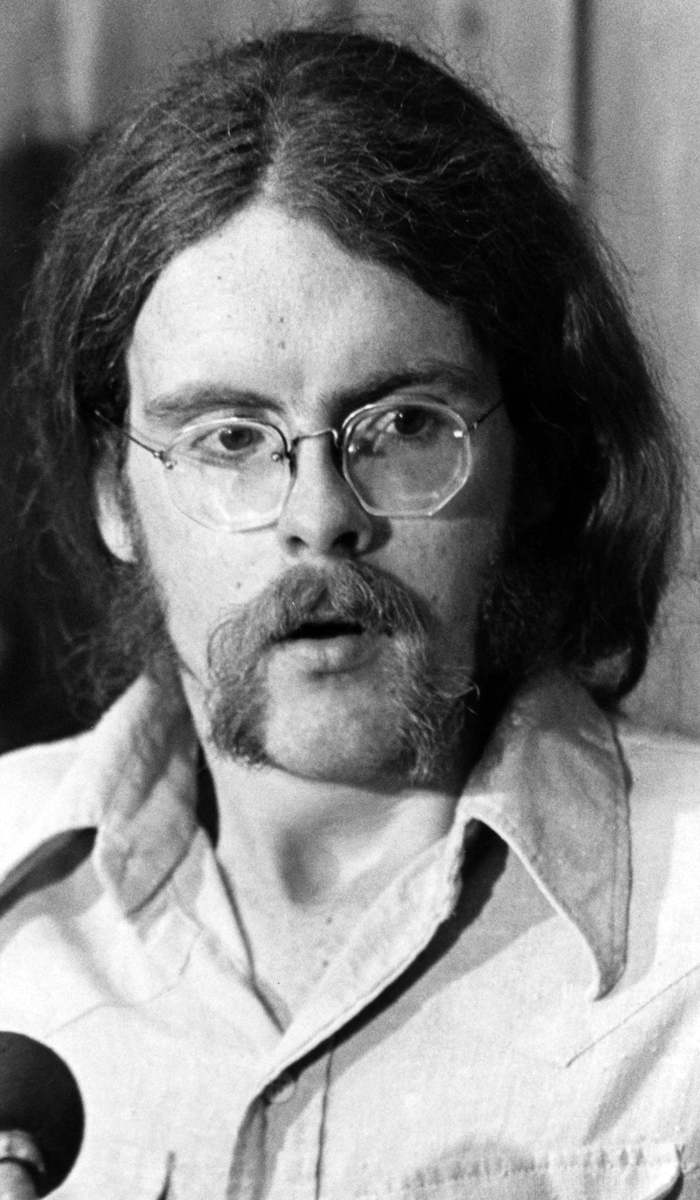

Tim ended up acting as the intermediary between the prisoners and the governor’s office over the phone, attempting to negotiate the next step.

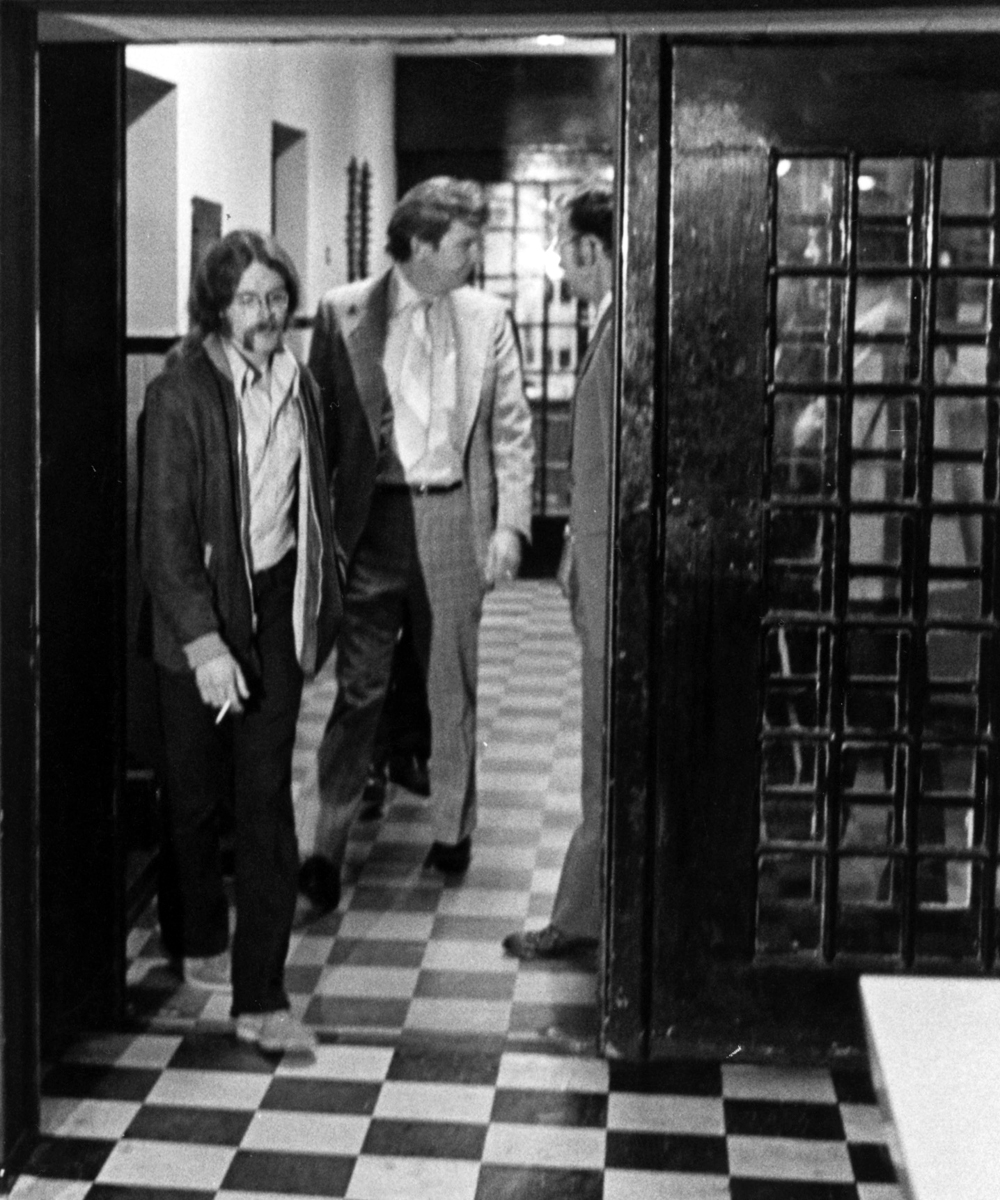

After six hours, the incident ended with the two doped up prisoners being taken back into custody. Within a short time, the local and national media were at the prison gates. A representative from the Department of Corrections hastily staged a press conference.

Now earlier, Tim had become acquainted with a local newspaper reporter who had previously interviewed him on the changes and improvements taking place to the medical services at Indiana State Prison. So, as the rep from the Department of Corrections opened up the press conference for questions, this reporter yelled out, “Tim, tell us what happened.”

“I ended up being the face of this story which was spread all over the national news,” he says. “It was my 15 minutes of fame.”

Days later, both Tim and Dr. Saylors returned to work. “It was one of those, ‘I’m getting back on the horse and I’m not going to let this take me down.’ I lasted about another year there.”

Future Employment

Tim returned to New Orleans and ended up working for the Health Department. “Not as a PA, mind you,” he says. They didn’t have PA certification in Louisiana or Indiana, both of which were Tim’s primary states at the time. He worked as a child development counselor for two years in some of the worst poverty-stricken housing projects in New Orleans.

Back again to his home state of Indiana, Tim became the associate director of the Center for Law and Health at Indiana University Law School, where he did health law research and ran grant-funded projects concerning health policy issues.

“There just weren’t PA jobs at the time,” says Tim. “Nobody really knew what to do with us. Indiana was my home and where my family lived. It was right behind Mississippi in terms of legalizing PAs for prescriptive privileges.”

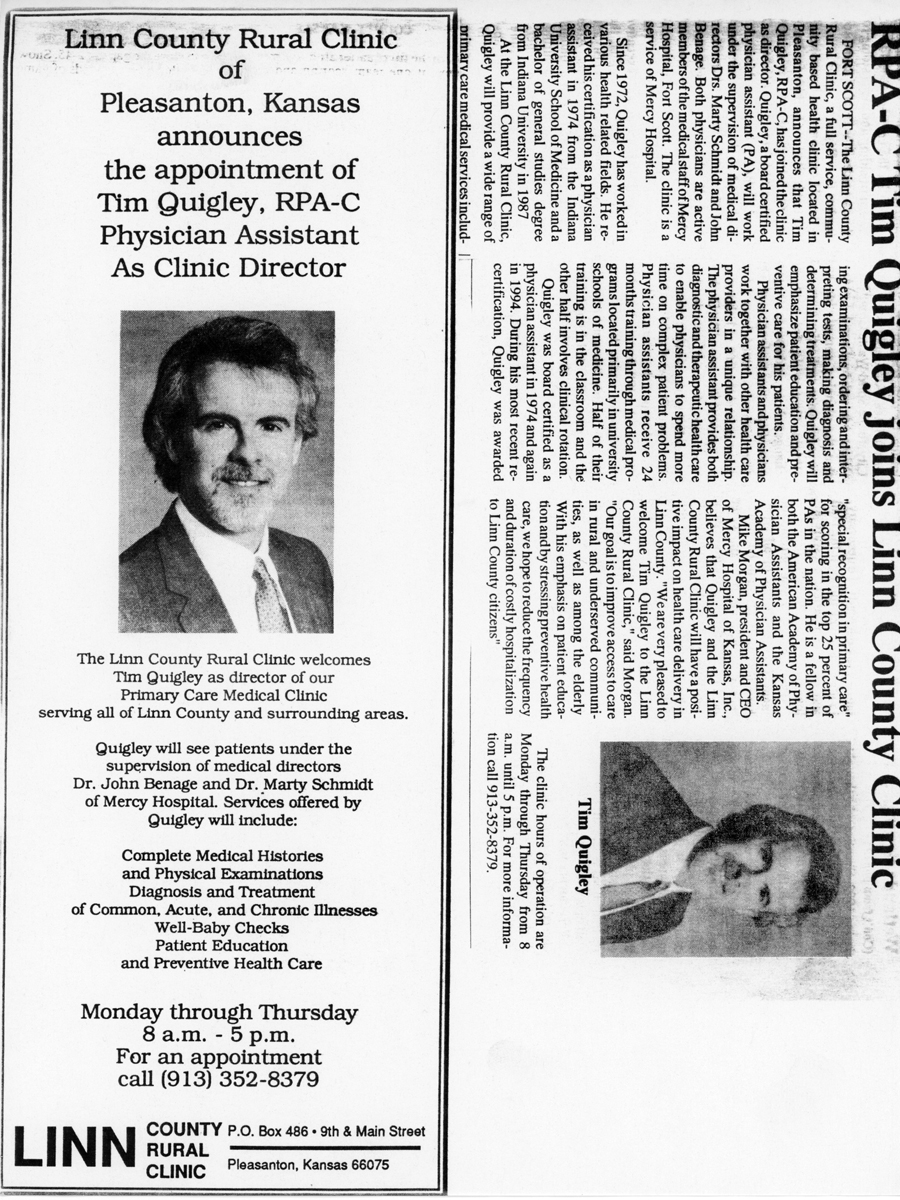

Tim Quigley’s first real PA job didn’t come about until he was in Kansas. Tim married a Kansan and moved to that state, where he started working at a rural clinic.

“I was the only provider in the county, and the supervising physician was a pediatrician of all things, and he was in the next county,” Tim says. At that time state law required a practicing PA’s charts to be signed every two weeks.

This supervising doc was based out of a hospital in Fort Scott, Kansas and would ride his motorcycle up to Tim’s clinic in the next county every other Tuesday. “We would eat lunch next to a stack of charts, talk about the cases and sign charts. Then he’d get back on his motorcycle and drive 30 miles back to Fort Scott, Kansas.”

Eventually, Tim moved to Wichita to join the Wichita State PA faculty. “I started working for a very large psychiatric group and I stayed with them for a long time.”

During his time on the Wichita State PA program, Tim was teaching and did inpatient and outpatient psychiatry with low-income chronic mentally ill patients. He also made hospital rounds at four different hospital psychiatric units. “I had a lot of intense experiences in that way,” he says.

During his time on the Wichita State PA program, Tim was teaching and did inpatient and outpatient psychiatry with low-income chronic mentally ill patients. He also made hospital rounds at four different hospital psychiatric units. “I had a lot of intense experiences in that way,” he says.

Of this particular role, Tim attributes his affinity for patients facing mental health challenges to his first entree into behavioral health while working as a 16-year-old orderly with the mentally ill at the Indianapolis nursing home. “Even when I was in PA school, we didn’t do a Family Practice preceptorship like they do here at MEDEX. You could choose your preceptorship, and I did mine in psychiatry with a psychiatrist that I really admired. I spent a lot of time training under him.”

In 2008 Tim Quigley received a call from Henry Stoll, PA-C, a longtime faculty member at MEDEX Northwest.

“I got to know some of the MEDEX faculty and Henry Stoll in particular while attending AAPA conferences,” Tim explains. “I liked Seattle because I had visited there a lot. My sister lived in Seattle.”

Henry Stoll talked to Tim about joining the MEDEX faculty. Things didn’t work out until another year or two later. At that time, Tim was unhappy with his job at Wichita State and was getting divorced. With Henry extending the invitation a second time, now was a good time for a change.

“The opportunity to teach behavioral health here at MEDEX has been great. I’ve really enjoyed it. It’s nice to be able to finish out my career with something I’ve felt passionate about since I was a kid.”